First published Oct 5, 2014 revised 12/2016

As we move towards our field trip to Van Dusen gardens, I think we should spend a bit of time on ‘What’ and ‘Why’ and how does it connect with the Dhalli Lama’s visit to our school.

First, let me make my intentions clear.

This is an art class, and in it, we learn to use our brains, hands, and hearts to produce works that will inspire thought and change. …change can come in so many ways.

We have started the year of with Mark making, sketching, and observation of the world around us. It is not a huge stretch to think that marks contain the energy of the artist- your marks contain your energy. And that this energy participates in the world around us. Newton’s Third law??? (Energy may be transformed from one form to another, but it can not be created nor destroyed) ok, maybe I’m getting a bit esoteric…

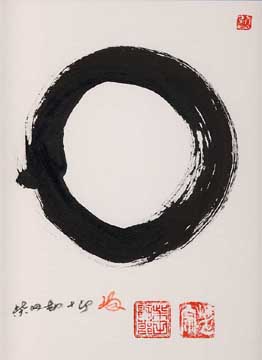

Image source https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ens%C5%8D

The Natural Cycle Seen through Circles

Circles are symbolically used to illustrate our complete life cycle. Either in the forms of sun worship, tales, religious arts, circle shapes portray the liveliest aspect of human being’s existence: perfection. In every period of time, circles connote the sense of serenity and completion. Carl Jung once wrote in his work that circle “is the archetype of wholeness.”

There is evident connection between human beings and circles. We are embraced by the horizon circle. We live in the round shaped planet revolving around the sun under the gigantic illuminating dome. We are enhanced by the love of the moon. Arts place importance on the natural shape which reflects abstract circle. The artistic works range from round shaped ring to wheels. We decorate radius above the saints’ heads and perform ritual sacred dance in a circle.There are several examples of the use of circle in Buddhism. The Buddha’s doctrine is called the wheel of dhamma or the wheel of truth. Zen further elaborates this concept by stating that once the wheel of dhamma is moved, it can go into 2 directions. Tibetan Buddhism practices ‘Mandala,’ concentric diagram portraying the universe and several aspects to reach spiritual tranquility. For Zen, it is called Enzo or circle drawing.

Enzo is the simplest form of Zen drawing. It is the symbol of enlightenment, power and the universe. It reveals the results of deeds and expression of present moment. Enzo is one of the most profound studies among zen painting, called zenga. It is believed that through Enzo drawing, the artists reveal their true characteristics clearly. Only those whose minds and spirits are fulfilled can draw a true Enzo. Some artists practice drawing an Enzo everyday as a kind of spiritual exercise.

Although the Enzo shape does not look complicated, its essence is difficult to reach and define. In a way, Enzo is simply a drawing of a circle done in one brush movement, in one breath. In another sense, the Enzo represents the completion of space. Some say Enzo has no true meaning while the others confirm it is indicative and demonstrates the continual action at a given time. When audience look at an Enzo painting, the painting communicates and is appreciated at different levels depending on the strength of the viewers’ minds.

Enzo shapes are various from symmetrical paintings to abstract forms. The brushed ink may be thin and soft or thick and rough. A number of Enzo paintings are accompanied with short messages or lyrics called ‘San’ written by the painters themselves or criticized by viewers to explicitly express religious or spiritual context of the paintings more profoundly. An Enzo painting functions as a clear metaphysical message or question, or as a demonstration to pinpoint or convey the nature of the truth. It reflects the artists’ understanding that ultimately no words or paintings can completely describe the truth. Zen scholars attempt to convey this message in the most straightforward way to guide us the true nature of truth instead of having a sitdown explanation.

The significance of direct guidance under religious practice has been passed on and refined in Zen Buddhism. Bodhidharma, the Zen founder elaborated this tradition as follows:

“…A special transmission outside the scriptures;

No dependence upon words and letters;

Direct pointing to the human mind;

And realising the enlightenment.”The guidance has many forms but one notable form of direct guidance which mostly relate to this paper is the use of art to introduce the minds to metaphysical questions which are the foundation of most zen teachings. For hundreds of years, the Enzo has been a guide to monks and practitioners to uncover the complicated questions posed by the masters. Sometimes, the Enzo itself is also present in the metaphysical questions

The Kamakura period (1200-1350 AD) marks the prosperity of the blending of zen culture. The art, lifestyle and religious teachings were unified and the art was developed into ‘Chado’ or tea ceremony, bamboo flute, Japanese garden, Noh theatre, pottery, ‘Kyudo’ or Japanese archery and most importantly ‘Shodo’ or paintings and poems. ‘Do’ means ways. These art forms are compared to ‘ways’ because they are knowledge clues to polish the artists’ self realization and understanding of the nature of the truth. Once all the knowledge is incorporated, it becomes known as “the artless art of zen.” The techniques have been passed on and used as the main tools to communicate the Zen’s truth.

Zen’s art is dissimilar to Buddhist art of other branches since it is not a symbol of other forms/objects. The objective of zen art is not to further refine the experiences of the adherents. The art is not used in worship, ceremony or praying. It is not even used to express disclosure, awakening or exposure of spiritual teaching. The zen art as a divine art form portrays what is beyond direct description. It helps transform our understanding towards ourselves and the universe and exemplify the abstract forms.

In traditional Zen art, paintings and scriptures are considered visual discourse. While poems convey the essence of Zen’s wordlessness, D.T. Suzuki wrote about these distinctive forms.

“…The art of zen has no purpose for usage or aesthetic pleasure;

Its purpose is to intensely train the minds so that the minds can

communicate the ultimate truth…”(Text source John Daido Loori, Enso, UK: Weatherhill Boston& London, 2007, Page XIII

D.T. Suzuki, Zen and Japanese Culture, UK: Princeton University Press. 1959, Page 31)

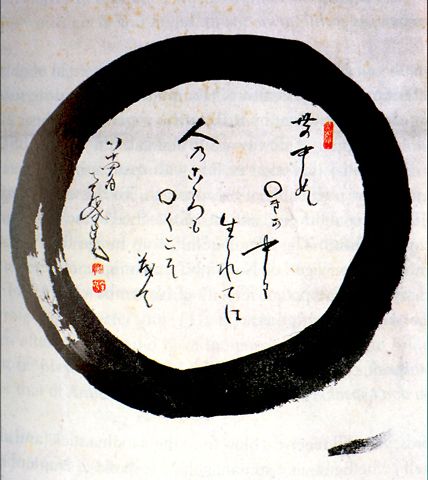

Image-source-laespatularoja-blogspot-com

Besides, there is Zen’s heritage we are yet to discover in terms of culture, literature and art. When the roots of training and practices are deeply established, it is time to appreciate other aspects of this cultural heritage as well as to understand the artless art of Zen more thoroughly.

However, in the end, we should consider the irrational Enzo or the Enzo which does not guide to the existence of other being but itself. It stands alone completely impeccably and holds artistic value in itself. The Enzo is a self-reward, exists for itself and does not affect others but itself. The end result of this Enzo is Enzo.

“…Just this one circle

No monk in the world can jump out…”

The use of circle imagery in Buddhism can be traced back to Sakyamuni Buddha myth (around 563 B.C.). According to the Zen master, Yun-men, after his birth, the Buddha raised his hands and pointed them to heaven and took 7 steps in circle and proclaimed himself the honored one. Circumambulation of holy venues such as stupa was a Buddhist tradition since the old days. However, in the early Buddhism concepts, attention was more drawn into emptiness than circle symbol. This notion was most fully developed in the Kapimala period by the 13th Supreme Patriarch of India (2nd-3rd Century). Kapimala was referred in Japanese master Keizan Jokin’s Denkoroku (1268-1325). Jokin stated that “when you strike space it echoes, and thus all sounds are manifested; transforming emptiness to manifest myriad things is why shapes and forms are so various. Therefore you should not think that emptiness has no form, or that emptiness has no sound. When you furthermore investigate carefully on reaching this point, it cannot be considered void and it cannot be considered existent either.”

The Patriarch Kapimala disseminated his teachings to the Bodhisattva Nagarjuna who invited and gave him the wishfulfilling jewel. Bodhisattva Nagarjuna asked “this is the most valuable stone in the world. Does it have form or is it formless?” The Patriarch Kapimala answered “You only know of having form or not; you do not know that this jewel neither has form nor is formless. And you do not yet know that this jewel is not a jewel.” At that moment, Bodhisattva Nagarjuna became enlightened and became the 14th Patriarch. It is also believed that Bodhisattva Nagarjuna was the first to write Prajnaparamita-sutra or intellectual and awakening scripture which is the oldest chapter tracing back in 100 years before Christ. It is the scripture which is a foundation for Mahayana Buddhism. In this chapter, the notion of ‘empty space’ reflecting ‘emptiness’ or ‘nothingness’ was much further developed than other writing pieces. Furthermore, this scripture brought about the concept of thusness, the highest state of existence, the 2 of which lead to the complete enlightenment. In other words, the current being is the perfect awakening. The result of these deeds shall not be increased nor reduced. The scripture chapter includes Mahaprajnaparamitahridaya-sutra, which state

“…Form is emptiness. Emptiness is form;

Form does not differ from emptiness. Emptiness does not differ from form;

(Text source Victor Sogen Hori, Zen Sand, USA: University of Hawaii Press, 2003, Page 469)

Image source photo by karen l darling on flickr

Whatever is form, there is emptiness. Whatever is emptiness, that is form;

Sensation, perception, volition, and consciousness, are also like this …”In prajnaparamita-sutra, Bodhisattva Nagarjuna elaborated the concepts of relativity that all things exist only by virtue of their opposites. Therefore, all things are randomly relative but without underlying essence, in other words, empty. This ideal gradually filtered into Zen Buddhism. The idea of “thusness” is recognised in Zen as enlightenment in daily life and the appreciation of simple, ordinary experiences and objects, as well as the idea of being in the moment without distractions.

As the creation of Enzo increased, so did the variation of themes and inscriptions accompanying the circles. Although some Enzo appear without inscriptions, most include some phrase or verse reflecting an aspect of Zen teaching. Shibayama Zenkei wrote that “in that brief expression of an idea, you see the writer’s spirit. That is the implicit flavor of Zen. . . . The choice of the inscription comes from that; the choice of the inscription is an expression of spirit. As a zen person, my heart is pulled in ways I can’t explain.”

Most broadly, Enzo represent the vast qualities of the universe, conjuring up its grandness, limitless power, and natural phenomena. But Enzo can just as easily represent the void, the fundamental state in which all distinctions and dualities are removed: ‘Outside — empty, inside — empty, inside and outside — empty.’ Very often Enzo depict the moon, symbolizing enlightenment, but can also represent the moon’s reflection in water, symbolizing the futility of searching for enlightenment outside oneself. Less philosophically, Enzo can simply represent everyday objects such as a dumpling, rice cake, basket or tea cup and the concentrating mind focusing on the drinking at the current moment.

“A circle is a window. it is peace, silence, perfection, and harmony. It is whole and unified. In contrast, angular forms represent conflict, agitation, and excitement. They suggest omission, unevenness, the partial and the particular. The two concepts oppose each other. However, to look at a Zen Enzo from this point of view is an absurd mistake. A Zen Enzo is drawn round, but the circle’s center conceals angles and within a four-sided angle is concealed a circle. The circle and the angle both conceal oneness. Within the center of the Enzo, truth reveals the life and soul of the ordinary circle and angle. This is the superior, absolute circle.”

(Text source Hori, Numerous Buddhist Texts, Page 191

Shibayama Zenkei, Zenga No Enzo, Tokyo: Shunshusha, 1969, page 7)

Image source www.wikiart.org