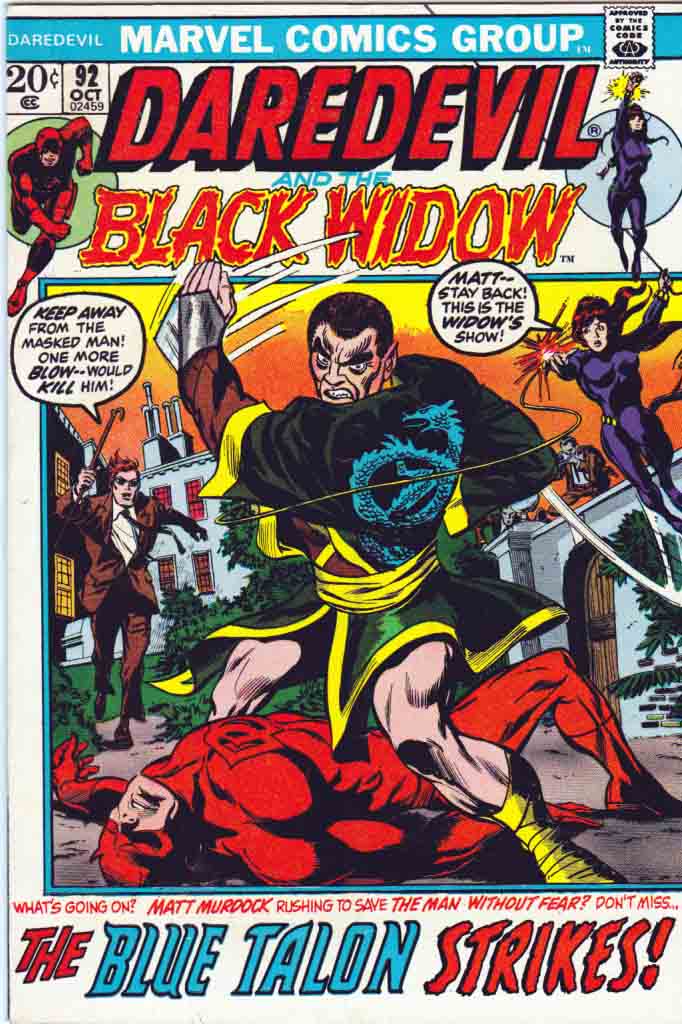

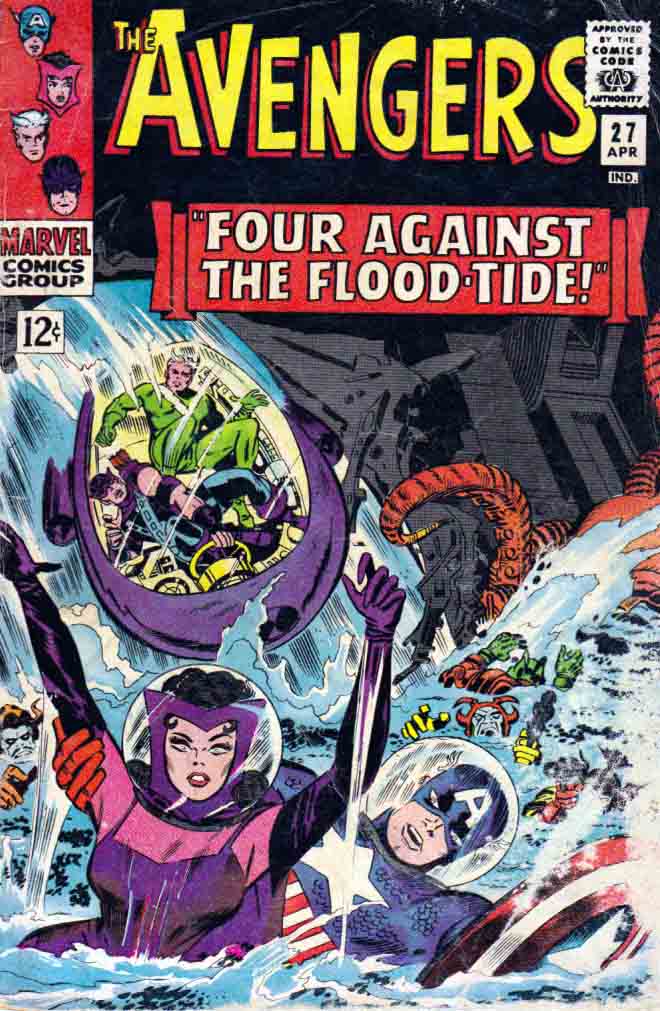

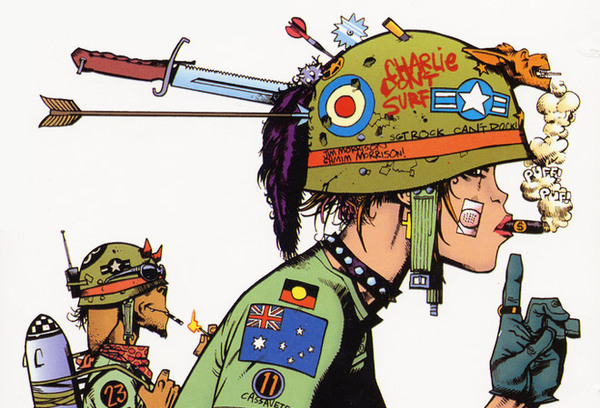

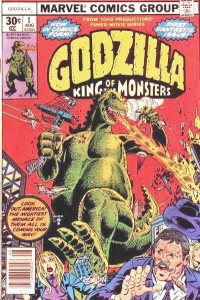

Image source comiconverse.com

What is a Comic Book?

A comic book or comicbook, also called comic magazine or simply comic, is a publication that consists of comic art in the form of sequential juxtaposed panels that represent individual scenes. Panels are often accompanied by brief descriptive prose and written narrative, usually dialog contained in word balloons emblematic of the comics art form. Although comic books have some origins in 18th century Japan and 1830s Europe, comic books were first popularized in the United States during the 1930s. The first modern comic book, Famous Funnies, was released in the United States in 1933 and was a reprinting of earlier newspaper humor comic strips, which had established many of the story-

telling devices used in comics. The term comic book derives from American comic books once being a compilation of comic strips of a humorous tone; however, this practice was replaced by featuring stories of all genres, usually not humorous in tone. (Wikipedia)

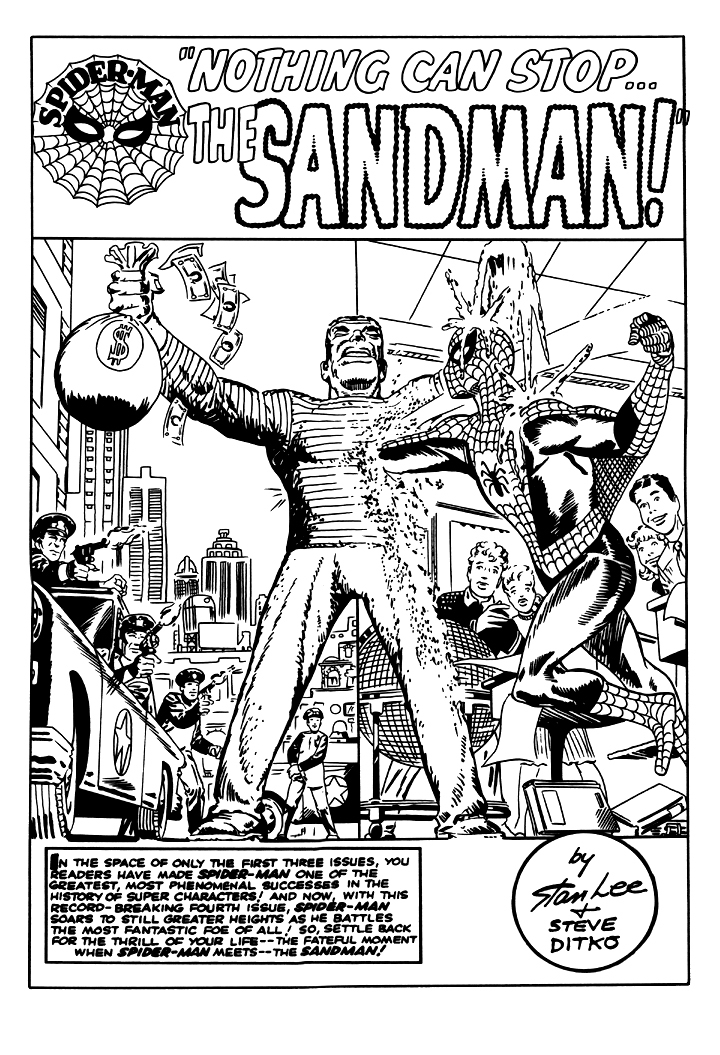

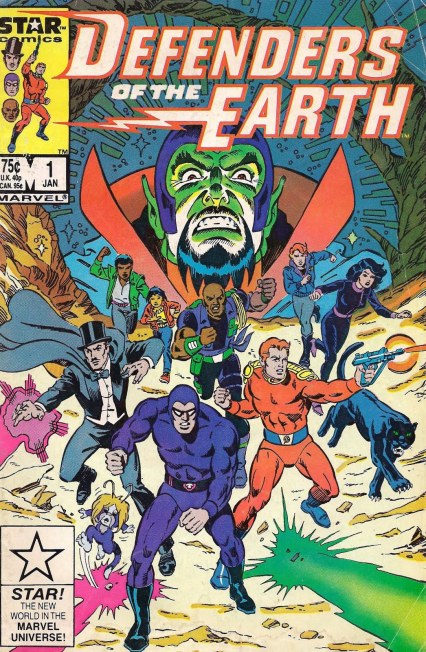

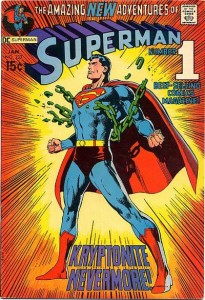

Image source www.newsarama.com

Procedure:

Follow the activities and the directions in this booklet!

Use your sketch book for much of your brainstorming and character development.

P1

Front Cover

Don’t touch until last!!!

Please include:

Main character

setting

Title

Credits

Barcode

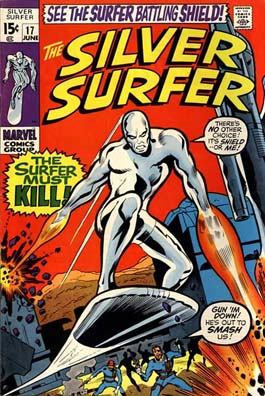

Image source charltonhero.wordpress.com

P2-3

Defining the project

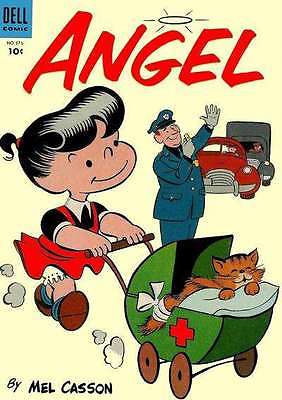

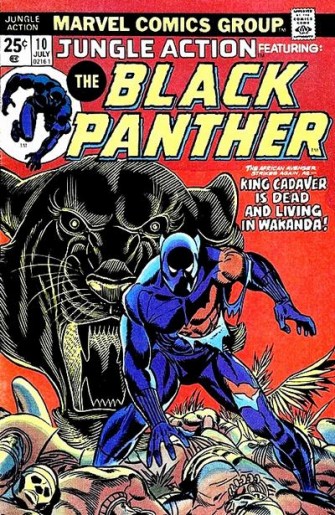

Image source www.actuarialoutpost.com

P4-5

Character Development

Answer all the question in the booklet. (use a pencil first, until you 100% positive)

Name:

Age:

Birth:

Death:

Gender:

Eye colour:

Weight:

Build:

Family:

Mum:

Dad:

others:

Personality type:

Life Story:

Ethical background:

Educational Background:

Goals:

Clothing style:

Accessories:

Likes:

Dislikes:

Flaws:

External traits:

Internal Traits:

Image source www-rarecomicbooks-fashionablewebs-com

Image source www-rarecomicbooks-fashionablewebs-com

Image source charltonhero-wordpress-com

Image source www-rarecomicbooks-fashionablewebs-co

P6-7

Follow the directions and sketch out your character.

P8-9

Draw out your location

Understanding speech bubbles and thought bubbles

Character monologue

Use this page to Play with at least Seven different text boxes and have your character give a speech. Please Draw your character in a setting from your story.

Image source quotesgram-com

P10-11

Panels and Layouts

Practice making different panels.

P12-13

Story Development

Parts of a story:

Exposition/introduction: is the insertion of important background information within a story; for example, information about the setting, characters’ backstories, prior plot events, historical context, etc.

Rising action: in a plot is a series of relevant incidents that create suspense, interest and tension in a narrative. In literary works, a rising action includes all decisions, characters’ flaws and background circumstances that together create turns and twists leading to a climax.

Conflict: The conflict in the story is often introduced in the exposition but is given more detail throughout the rising action. The conflict can be between characters (man vs. man), between a character and societal norms or values (man vs. society), between a character and natural forces (such as weather or animals), or between a character and him or herself when he or she has an internal struggle (man vs. self).

Climax: (from the Greek word »¼±¾, meaning “staircase” and “ladder”) or turning point of a narrative work is its point of highest tension or drama or when the action starts in which the solution is given. Climax is a literary element.

Falling action: is defined as the parts of a story after the climax and before the very end. An example of falling action is act four in a five-act play.

Denouement/resolution: the final part of a play, movie, or narrative in which the strands of the plot are drawn together and matters are explained or resolved.

Image source picclick.ca

TIPS

Only little kids and the immature really stick with comics that offer nothing but action and titties. You NEED a story. And not just any story, but a really good story. With substance.

And how do you get ideas for such plots? DON’T JUST READ COMICS. Read books. Watch movies. Listen to music. Comics in general don’t get the emotional reaction that a great novel or movie do.

And to make a great comic, you must engage your reader’s mind and emotions. You can be sure that almost anything you come up with has already been done. What you need to do, is spin it in a direction no one’s seen before.” (By Nate Piekos)

5 Rough plot Ideas

Please write your ONE page story on the back of this booklet.

*** You are WELCOME to type the story up, and glue it into the box on the back!!!

P14-15

Storyboard your idea

Notice that the first spread p1-2 is your Splash page!

Larry Hama posted these on FB the other day. I stole them so we could talk about them.

These are my ten rules for drawing a comic book page, that sums up what I have learned in forty odd years in the biz. They are not universal, they are my own personal guidelines, so there is nothing to disagree about.

1. Don’t have people just standing there.

2. ANY expression is better than a blank stare.

3. Avoid tangents, and any straight line that divides the panel.

4. If you use an odd angle in the shot, there has to be a reason for it.

5. If you don’t have at least one panel on each page with a full figure, your “camera” is too close.

6. Plan out your shots in “Lawrence of Arabia” mode rather than in “General Hospital” mode.

7. Don’t think of backgrounds as “things to fill up the space after the figures are drawn.”

8. If you know what something is called, and you have an Internet connection, there is no reason to draw it inaccurately.

9. If the colorist has to ask if a scene takes place at night, you haven’t done your job.

10. If you can’t extend the drawing beyond the panel borders and still have it make visual sense, you’ve cheated on the perspective

P16-31

Comicbook good copy

Refer to you storyboard!

Keep your style the same

Start in pencil-

Finishsh all panals befor you Ink up

P31

Self Evaluation

What did you learn during this project?

Did you enjoy this project, why or why not?

How many hours did you spend on this project?

What would you do differently next time you make a comic?

Write out a written description of the original character.

What is the character’s name? What type of character will it be?

Describe the personality and what type of events or circumstances the character might be involved in. Will the character have a supporting cast or a side-kick? Will the character have props or a special environment that they live in?

Begin making thumbnail sketches of what the character might look like. Take one idea and continue to develop the character showing both a frontal and side view. Include the full body and any props the cartoon will need. Add color and detail.

Look at different layouts of a comic strip.

Sketch ideas in each panel. Think about point of view, size, cropping, and the rule of thirds when designing each panel. Turn in rough draft for approval. Transfer rough draft to final draft paper. Draw lightly in pencil. Add lettering, detail and color. Finish with a fine point marker outline.

Comic Book Cover. . Create a rough draft book. Include the title, character, background, props, captions, etc. Think about point of view, size, cropping, and the rule of thirds, and a border when designing the cover. Turn in rough draft for approval. Transfer ideas to the final draft. Draw lightly in pencil, add color and finish in marker. The cover design should include details such as a bar code, price, and other details found on a real comic book cover.

Image source tankgirl.wikia.com

Marking Criteria:

Character development 5

Character sketches 10

Character monologue 10

Plot development 5

One page story 25

Storyboard 20

16 page comic 100

The cover design 20

Self Evaluation 5

Total Marks 200

DO YOUR BEST! & DON’T BE BORING!

Comic Books For Beginners

Comics Vocabulary

Juxtapose – to place close together or side by side.

Comics – the phenomenon of juxtaposing images in a sequence

Industrial process – comics are created as a collaborative product with the task of developing comics divided between writer, artist, inker, etc (like an assembly line).

Artisan process – comics are created by an individual cartoonist who does all the creative work (drawing, writing, etc).

Simple narrative – the story revolves around a problem and ends with the resolution of that problem (like a children’s book).

Complex narrative – the main plot is extended by back story, character development, and ongoing subplots (like Harry Potter)

Anti-narrative – may contain narrative elements such as setting, characters, and action, but these elements do not tell a comprehensible story. The artist is trying to evoke a mood from the reader, or creating the art just to be appreciated.

Braided narrativity – narrative that follows the intertwined destinies of a large cast of characters. Has no global plot, but a number of sub plots (like a soap opera).

Proliferating narrativity – the main plot functions as a support for the telling of adventures and anecdotes, accumulating many little stories. It is a mythos (most super hero comics).

Synecdoche – using a part to represent a whole.

Sequence metaphor – two juxtaposed images that together create a meaning not present in either image alone.

Splash page – a full page panel, usually at or near the beginning of a comics narrative and used to establish the situation in which a story begins

Chiaroscuro – a stark contrast of light and dark to funnel attention to a particular point in a panel.

Onomatopoeia/onomatopoetics – a word that imitates or suggests the source of the sound that it describes.

Image source tomtificate.wordpress.com

Image source thelongboxproject.com

Image source www.comicsreporter.com

Image source comicvine.gamespot.com

Plot Templates

Here are some of the most helpful.

The most simplistic plot template

- Adventure comes to you. A Stranger comes to town.

- You go to Adventure.You leave town.

Plot template

- Character oriented story, the protagonist searches for something and winds up changing him/herself.

- Plot oriented, this features a goal-oriented series of events.

- This is the typical Chase Plot. Definitely action-oriented.

- Another easy to recognize action-oriented plot.

- A variation on the Rescue is when the protagonist escapes on his/her own.

- Ah, character comes back in with this one. Someone is wronged and vows to take revenge.

- The Riddle.Love a good mystery? This is the plot for you.

- Character oriented, this story follows two main characters, one on a downward track and one on an upward track and their interactions.

- Everyone is the US roots for the Underdog. This is the plot where the under-privileged (handicapped, poor, etc) triumphs despite overwhelming odds.

- Pandora’s Box extended to novel form.

- This is a physical transformation of some kind. If you recently watched the movie, “District 9”, you’ll recognize this plot form. It’s Dracula, Beauty and the Beast, or the one I remember best is The Fly.

- Similar to the previous, this plot features an inner change, instead of changing the outer form.

- Bildungsroman, rite of passage, coming-of-age–these terms all refer to someone growing up morally, spiritually or emotionally. Often, it’s just a hint of growth, or a tiny change that hints at larger changes.

- The classic Boy-meets-Girl plot.

- Forbidden Love.Oh, hasn’t Stephenie Meyer milked this one in herTwilight series? Brilliant use of the forces that keep her characters apart, while still attracting.

- From the Biblical tale of Jesus to the story of parents sacrificing for their children, this is a staple of literature.

- You know those secrets you’ve buried deep in your past? This story digs around, exposes secrets and watches them affect the characters.

- Wretched Excess.When a character is in a downward spiral from alcohol, drugs, greed, etc. this is the plot form.

- Ascension or Descension. A rise or fall from power puts a character into this plot form.

Hero’s Journey: Adapted from Joseph Campbell’s Mythic Hero

- Christopher Vogler’s explanation of the Hero’s Journey is excellent. The basic stages, along with the corresponding character arc are these:

- Ordinary World – Limited awareness of problem

- Call to Adventure – increased awareness

- Refusal of Call – reluctance to change

- Meeting the Mentor – overcoming reluctance

- Crossing the First Threshold – committing to change

- Tests, Allies, Enemies – experimenting with 1st change

- Approach to the Inmost Cave- preparing for big change

- Supreme Ordeal – attempting big change

- Reward – consequences of the attempt

- The Road Back – rededication to change

- Resurrection – final attempt at big change

- Return with Elixir – final mastery of the problem

- You write comedy or humor and want a plot for a novel?

John Vorhaus, in The Comic Toolboxadapts the hero’s journey into a Comic Throughline.

For the Teacher

By

Amelia Carl & Corey Creekmur

Understanding and Creating Comics Lesson Plans

- Pass out the Comics Vocabulary paper. Students will keep this in their Language Arts folders for the entire unit, using it to study for their comics vocabulary quiz and as a reference during analysis. Begin the unit by defining JUXTAPOSE and COMICS. This way students will know exactly what is meant by the term comics, how many different types of stories it describes, etc.

- Begin with a discussion to ascertain what the kids already know about the subject, and what stereotypes or assumptions they may already have. Have kids volunteer to write down items in two columns on the board: COMICS I READ and WHERE I READ THEM. An example would be, “Garfield, in the newspaper at home.”

Homework: Students write a paragraph answering the following questions: Who reads comics? Who are comics for? Describe your own comics reading habits (if any). Have you ever seen a movie or a TV show with characters from comics? What did you think?

- Frontload students with a presentation on the history of comics. Have them fill out a presentation companion with 3 questions and 2 connections. If their questions are answered in the course of the presentation, they can also fill in the answers on their worksheet. This will be collected for points. This would also be a time to show a documentary if a suitable one is found and there’s enough time to show it. Vocab: INDUSTRIAL PROCESS, ARTESAN PROCESS

- Discuss, as a class, the difference between content and form. Give examples of each and have students take notes. They will use these notes in an upcoming small group activity. Project an image of a comic strip up on the board and analyze it first for content, then form. Slowly release control of the discussion to the students and allow them to spy examples of each.

- Put students in groups of 3-5. Each group needs their notes from the previous discussion, as well as a “scribe” to continue taking notes as they participate in a small-group analysis. Each group will receive a comic strip and a comic book, and they are to read and analyze both for form and content. After analysis, they are to compare the two for similarities and differences. Teacher observation may be required to prompt students along and keep kids on task. Vocab words: SIMPLE NARRATIVE, COMPLEX NARRATIVE, ANTI-NARRATIVE, BRAIDED NARRATIVITY, PROLIFERATING NARRATIVITY

- Student groups will do a short, informal presentation of their analysis for the rest of the class. Analysis notes will be turned in for credit, and each group will be evaluated by the teacher for the quality of their presentation (see rubric).

- Students will create a poster-sized comic strip using the Industrial Method. They all must contribute to the whole. They can do this by assigning jobs (inker, letterer, etc) or having one person do each panel. Have them write a paragraph after sharing their poster with the class. Was this easy or hard for you? What made it easy or difficult? How were you able to complete the assignment? Who had what job? This paragraph will be turned in for

- DAYBOOK: During this portion of the unit, I will be incorporating lessons I’ve “scavenged” from the Daybook of Critical Reading and Writing (see photocopies). Some of this section was lifted from the teacher’s guide to this series. The big difference here is that the Daybook is supposed to be a consumable, but we can’t afford to keep buying them, so I use them as a textbook and kids write on their own paper or worksheets I’ve made.

Daybook “Day One:” Describe to students what is expected of them in this unit. “Through excerpts of graphic novels, you will learn the importance of interpreting visual text. Comprehending visual text requires learning a new set of skills and applying previously learned skills to assist with reading words and pictures.”

- Provide students with background information: “We’ll be reading excerpts from the Bone series of graphic novels by Jeff Smith. Born in the American Midwest, Jeff Smith began learning about cartooning at an early age from the comic strips, comic books, and animated shorts on TV that so captivated him. He started drawing the Bone series in kindergarten and founded his own animation studio at Ohio State University. Bone has been reprinted and translated into 13 languages.”

- “The characters in this series are the Bone cousins, creatures with some human characteristics and some special powers. Phoney Bone concocts scams that often result in chaos. Fone Bone is kind of the main character. He has the ability to cope with almost any situation. Smiley Bone participates in outlandish plots with no hope for success. Thorn, a girl who befriends Fone, is one of several human characters the Bone Cousins meet in the course of their adventures and escapades.”

- Read the explanatory text on MAKING INFERENCES. I have reproduced this page as a handout to avoid having the kids write in the book. What can they tell about the story, characters, plot, based on one frame? Students will write their answers/observations solo, and then discuss as a class. Vocab Words: SYNECDOCHE, SEQUENCE METAPHOR, SPLASH PAGE.

- Discuss the first panel of the selection on page 135 of the Daybook (“You know what I want? Some honey!”). Read the panels aloud, giving parts to read (Fone, Thorn, and Tom.)

-What can you tell about Fone in this frame? What do the hearts mean? Facial expression?

-How about the panel right below it?

- Discuss sequence. “Authors of graphic novels use several ways to suggest the passage of time and sequence of events. They can use the shape of the panel (a wider rectangle might seem to indicate a longer passage of time) the white space around the panel, and the words within the panel. It’s still up to the reader to fill in the gaps by making inferences. That means that comics are read differently by different readers who have had different experiences and perceptions. “

- Have students look at the 2nd and 3rd panels, which are connected by Thorn’s sentence. Ask them how much time has passed between this frame and the next. Ask about frames 3-4, then the 3rd row series.

- Have students look at Fone’s facial expressions (and the expressions of other characters).

- Students will work on the inference chart alone first, and then share with a partner. I have reproduced this chart to avoid writing in the book.

Daybook “Day Two”

- Put the following words on the board for clarity while reading. I like to have the kids try to guess what words mean like, “Cupie might be like Cupid because they’re spelled the same.” It gets them thinking about spelling and word roots etc.

cupie — variation in spelling of kewpie doll, an early 1900’s doll with a round body and a wisp of hair.

toddle — to walk unsteadily (ie toddler)

carnie — a mildly insulting slang term for carnival worker

- Provide students with background knowledge. “Beekeepers use a smoker (a portable firebox with a nozzle and bellows) to extract honeycombs from beehives. The smoke dulls the bees’ receptors so they can’t warn the colony of invasion, and makes them drowsy. Once the bees are subdued by the smoke, the beekeeper can remove the honeycombs from the hive.” Vocab Words: CHIAROSCURO, ONOMATOPOEIA. (set the date for the quiz so kids have time to study!)

- Read the panels of the next section (“Why don’t you lose the cupie doll” and “That’s enough!”), dividing up the parts again. Ask students how they knew which words to emphasize as they read. Discuss text differences and other “formal elements” of the genre.

-variations in text appearance

-speech balloons

-thinking bubbles

-mood symbols (surprise lines, anger lines)

- Pass out Comics: Characteristics. Have them fill out the prediction and share with a partner. Have students write about how they read the panels of Bone… left to right, top to bottom, diagonal, and why? Discuss Fone Bone and his relationship with Thorn. Ask students about how Fone separates Tom and Thorn, and then have them write their responses.

Daybook “Day Three”

- Give students the vocab words.

maiden – a young or unmarried woman

foreboding – the feeling or notion that some future evil or misfortune will come to pass.

Grim – ghastly, repellant, savage, serious

adjacent to – next to, adjoining, neighboring

- Discuss visual elements of genre. What do horror movies look like? (they are dark, shadowy, lots of “jump out and surprise” moments vs. bright, colorful comedies etc.) Comics work the same way.

- “Similarly, there are genres of graphic novels and comics, including fantasy stories, historical fiction stories, nonfiction stories, and super heroes. Various style elements are typical of each sub genre. Nonfiction pieces tend to have straight lines, subdued colors. Same with historical fiction. Super heroes have bright colors, curved lines.”

- Get ready to read Lizzie Borden selection. Read students this excerpt: “Lizzie Borden was 32 years old when she reported that her father and stepmother, with whom she lived, had been killed. Lizzie was charged with the murders, and the circumstantial case against her was strong. The facts at the trail were presented as the following: both Bordens were slain with an ax, although witnesses saw no trace of blood on Lizzie after the murders, three days later a friend saw Lizzie burning a dress she claimed was paint stained. No other relatives or servants in the home were charged with the crime. Nobody was ever convicted. Lizzie was acquitted but she lived in the shadow of the crime her entire life. “

- Read intro to selection. “Artists who write and illustrate graphic novels use such elements as lines, depth of field, and space to convey their ideas. The choices artists make about the design of the visual images contribute to their individual styles. In The Borden Tragedy, Rick Geary presents the story of Lizzie Borden, who was accused of using an axe to kill her father and stepmother in 1892. Although she was found not guilty, suspicion remained, especially since the murderer was never found. Geary claims that his story has been “excerpted and adapted from the unpublished memoirs of a thus far unknown lady of Fall River, Massachusetts.” As you read about Lizzie’s visit to Alice Russell on the night before the murders, pay attention to the art as well as the words.”

- Read selection, assigning parts — discuss narration bar at the top of each page. Narrator and Lizzie are the characters that need readers.

- Students will use notebook paper to create a compare/contrast Venn diagram individually. They will compare the art and other elements of Bone vs. Lizzie Borden. Then discuss as a class. Have them answer the following question on the other side of the paper with their diagrams. COMPARE JEFF SMITH’S STYLE IN BONE TO RICK GEARY’S IN THE BORDEN TRAGEDY. WHICH STYLE DO YOU PREFER? WHY? They need at least 5 sentences. This response and the venn diagram are homework.

- As a class or in small groups, allow students to thumb through the comics packet of examples that I’ve drawn or collected. Have them identify elements of form and content in an informal discussion. This packet may be used for reference during comics creation and analysis.

- It is finally time to create comics. I plan to start with a one page comic that includes at least three panels (more of a comic strip). The content is up to the kids to choose, but they are required to use recognizable formal elements of comics (perhaps choose from a list, say choose three of five, etc.)

- Students will take the Comics Vocab quiz.

- Comics Show ‘n’ Tell (Carter). Students are put in pairs. Each student writes a comics script with dialogue and action. This will be scaffolded with examples. Then they will give their script to their partner and they will turn the short script into a short comic. Questions that will arise in discussion: how can you write your script in a way that conveys how you want your comic to look visually? What kinds of words can you use that evoke images in the artist’s mind?

- Depending on how much time remains for the unit, I’d like to assign more comics to make and push the students to use more formal elements. One option would be to do a poetry comic (as seen in the last section of the Daybook excerpt), or a song lyric comic (translating a poem or song lyrics into a comic, see the “Annabel Lee” example). One of these will be the culminating project.

Amelia Carl

Corey Creekmur

008:190:SCA

American Comic Book

Unit Rationale: Comics in the Classroom

One of my favorite things about teaching Language Arts at Mid-Prairie Middle School is the freedom to choose what I teach. I am still responsible for covering the standards and benchmarks and doing my part to support the curricular “spiral” but for the most part I choose my own teaching materials. For example, in 7th grade I need to teach plot, character, setting, and theme, but I get to choose the novel I use to teach those things. This allows me to select stories and genres that I’m passionate about, and that passion keeps the kids interested and excited in their learning. The first reason why I chose to do a unit on comics is because it’s something I’m fascinated with and I know my enthusiasm will be contagious.

I designed this comics unit with my students in mind. I teach at a small, rural middle school. This particular class has a little over eighty students divided into four Language Arts sections. Our school population is 26% free/reduced lunch. Our school district is 200 square miles wide and contains many farming families. We are also a fully included school, meaning I have special education students in classes alongside my most gifted. All receive the same instruction; we just modify things for the IEP students based on accommodations. Our opportunities for gifted instruction are minimal. Needless to say, I have many different types of learners in my classroom and I wrote this unit with the intention of engaging as many of them as possible.

Teacher-researcher James Bucky Carter states in his book Building Literacy Connections with Graphic Novels, “There is a graphic novel for virtually every learner in your English language arts classroom” (1). Though we aren’t studying graphic novels per se, I believe comics have a lot to offer my reluctant readers, and are still complex enough to engage strong readers (especially in terms of creativity and analysis). “Learners can attain higher levels of achievement through their engagement with the arts. Moreover… learning in and through the arts can help ‘level the playing field’ for youngsters from disadvantaged circumstances” (Fiske qtd. in Carter 3). The use of pictures makes comics easier to understand for those who struggle with reading while the additional meaning-making of visual information can challenge stronger readers who aren’t used to critically analyzing visual information. Teaching my students to scrutinize the visual and textual elements of comics allows them to enter in at whatever level they are most capable, and to take the analysis as far as is possible through scaffolded instruction and collaborative learning. These higher order thinking skills are necessary for all students and with comics they can practice them successfully (and maybe have fun while they do it).

I want to teach an art-rich curriculum in a high-stakes testing educational environment. I am using comics to train my students in visual literacy and independent thinking. This is my form of resistance against the current educational climate. I want to teach my students not to go for a grade or a test score, but how to think. “We think of the English classroom as a place for students to develop their thinking skills. We do this through a variety of texts and genres. We devote our instructional time to developing students’ thinking skills so that they can understand, learn from, and appreciate what they read” (Fisher and Frey 26). While some of these elements are reflected in the standardized tests my students take (like reading comprehension) it is essential for teachers to see the bigger picture when it comes to their students’ learning – beyond the next big test and into their futures as learners. Therefore this unit is in compliance with preparing my students for their ITBS and MAP tests (focusing on reading comprehension and vocabulary) without being ABOUT the tests. “Graphic novels… are the perfect blend of word and picture, story as text and story as art. As such, they offer important, unique, and timely multiliteracy experiences” (Carter 7).

Comics promote visual literacy, which I believe is a critical skill. The Iowa Core Curriculum is being created in order to move our schools, our teaching, and our students into the 21st century. I believe visual literacy is a 21st century skill. The International Visual Literacy Association defines visual literacy as

… a group of vision competencies a human being can develop by seeing and at the same time having and integrating other sensory experiences. The development of these competencies is fundamental to normal human learning. When developed, they enable a visually literate person to discriminate and interpret the visual actions, objects, and/or symbols, natural or man-made, that are [encountered] in [the] environment. Through the creative use of these competencies, [we are] able to comprehend and enjoy the masterworks of visual communications (Fransecky & Debes qtd in Carter 12-13).

It’s abundantly clear that we live in an increasingly visual society. The internet is a perfect example of these emerging patterns. Comics can help teach symbol recognition, integration, and organization of visual elements. “Reading comic books requires a different type of literacy because on the comic book page the drawn word and the drawn picture are both images to be read as a single integrated text” (Duncan and Smith 14). When students are exposed to a new type of text, they need to know how to stop and say, “How do I read this? I can’t read this with the other literacies I’ve developed before. I need to teach myself a new way to read, experience, and analyze this.” With comics, one can see a “dynamic and hierarchical thought process – just like in language” (Cohn qtd. in Carter 12). I am envisioning this unit as an introduction to how to teach oneself a new literacy.

As a teacher, it is important for us to acknowledge our weaknesses. Mine is teaching writing. I feel like I have a pretty good handle on reading – there is a lot of emphasis on teaching reading strategies due to the critical state of reading test scores. My district has done an excellent job of providing opportunities for teachers continue their own education in this area. However, the teaching of writing has somewhat shoved to the side, as writing is not something tested by ITBS and examined by the government to determine if we are a school in need of assistance.

I have not received as much training in the teaching of writing, and I know middle school students are heading to high school with limited writing skills and a severe difficulty coming up with original ideas. All the high school English teachers complain about it, which of course you hear about through the “grape vine.” My former students not only lack organizational skills, but something Carter calls authentic student voice. Authenticity encourages students to read and write texts that mirror those of highly literate, proficient adults. To encourage authentic writing during the comics unit, I borrowed instructional ideas from Carter’s Comic Book Show’n’Tell activity, where students write a script for a comic book, and pass it on to a partner who draws the comic based on the script. In his words, the activity “engages students in a writing workshop on authentic voice, editing, and details. As a result, students develop a metacognative sense of the creative enterprise as a whole, while enjoying the opportunity to create an authentic text, a true student classic of sequential art” (152). Adapting this activity for my students is challenging me as a teacher of writing to incorporate more writing instruction in my classroom, and for this instruction to be unique and challenging for all levels.

Though learning new ways to promote creative and nuanced student writing are exciting, reading skills and strategies cannot be ignored either. I believe my students are served well in this area by participating in this unit. One of the most important aspects of reading is using the imagination to visualize what is happening on the printed page. This is something that research proves that good readers do and what struggling readers have a hard time doing consistently. “Drawing, charting, mapping, and other forms of graphic response also serve the range of learning styles that exist in any real classroom… Many times, drawn or graphic response can capture [the important] elements [of a text] more than words” (Daniels and Stieneke 93). If students are drawing their own comics, they are exercising their mind’s eye. If they are taking a poem and turning it into a comic, they are translating a printed text into a visual one using their own process of internal visualization, which will help them become more engaged readers. Jeff Wilhelm reports in his classic text You Gotta BE the Book! that comics helped his less enraptured readers fully enter the story world. “…the pictures, paired with words, helped less engaged readers to visualize the action of a story and to understand how words suggest various characters, settings, and activities” (119). Wilhelm suggests numerous times that teachers need to widen their definition of what types of texts are included in the word “literature” and that comics deserve a place under that heading. He’s not the only one. “From the very beginning of the new boom in graphic novels, librarians and teachers were at the forefront of rejuvenating the American comic book” (Lopes 165). I believe comics are making positive progress in the educational community and I am thrilled to be a part of this movement. They are a legitimate and literary art form that can be used in many vital ways in the classroom.

Works Cited

Carter, James Bucky, ed. Building Literacy Connections with Graphic Novels: Page by Page, Panel by Panel. Urbana, Ill.: National Council of Teachers of English, 2007. Print.

Daniels, Harvey, and Nancy Steineke. Mini-lessons for Literature Circles. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2004. Print.

Duncan, Randy, and Matthew J. Smith. The Power of Comics: History, Form and Culture. New York: Continuum, 2009. Print.

Lopes, Paul Douglas. Demanding Respect: the Evolution of the American Comic Book. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 2009. Print.

Wilhelm, Jeffrey D. “You Gotta Be the Book”: Teaching Engaged and Reflective Reading with Adolescents. New York: Teachers College, 1997. Print.