OAKRIDGE SCHOOL, 1951 – 1976

This history was written in 1968 by Lloyd Hamel, a teacher at Oakridge School. It includes an appendix that brings Mr. Harmel’s history of the school up to date. The photography was done by Marjean Gibson, Audio Visual Services, Vancouver School Board.

The history of Oakridge School could be looked upon as a history of how a community met a social and educational need. One of the general purposes upon which the educational system in British Columbia has been based, is that pupils within the system will ultimately take their place in society and hopefully make some contribution to it as self-supporting individuals. It has been a natural outcome, therefore, that such a system should exclude pupils who, because of a mental handicap, will never become totally independent of the care of responsible adults.

One group of such handicapped children are classified as the “trainable” mentally retarded. Their intelligence quotients lie roughly between 25 and 50, a range lower than that handled by special class facilities in the normal school.

Prior to 1951, Vancouver’s “trainable” retarded population was unknown to most citizens. Whether out of fear, guilt, hopelessness or lack of organization, parents of the retarded remained silent as to their children’s special needs. However, this changed in September, 1951, when Mrs. J. Purdy tried to enroll her retarded son in the Vancouver school system. Her feeling was that as a city taxpayer, she had this right as her son was of school age. Although the school authorities were sympathetic to her reasoning, they rejected her request on the basis that they were not legally responsible towards trainable retarded children. Section 158 of the Public Schools Act was used in support of the School Board’s position.

It read: (1) The Board of each school district shall (a) except as otherwise in this Act expressly provided, provide sufficient school accommodation and tuition, free of charge, to all children of school age resident in the school district . . . .

(2) It is not incumbent of a school district to provide school accommodation for a child to attend Grade 1 unless . . . .

(b) he has attained a standard of education equivalent to that of pupils attending Grade 1 in the school to which he presents himself . . . .

Miss Ruby Kerr, the School Board’s psychologist, encouraged Mrs. Purdy to begin a program for retarded children in a home. At first, Mrs. Purdy doubted the value of such a move for she had no training in the field of education. However, convinced that Woodlands School (a provincial institution for the mentally retarded) was not the place for her son as suggested by Dr. Kirkpatrick at the Child Guidance Clinic, Mrs. Purdy began to think seriously about Miss Kerr’s idea of a home training centre.

In January, 1952, she sent letters to twelve parents whose children had been turned away from a special class by the School Board’s Bureau of Measurements. The parents were asked to meet in Mrs. Purdy’s home if they were interested in starting a day training centre for retarded children. Eight parents responded, including Bob Moore, Business Editor of The Province newspaper. The group formed at first under the name of the Association for the Advancement of Retarded Children.

Both Mr. Moore and Mrs. Purdy were aware that the success of their organization would depend on their gaining public support. The following article was published in the Vancouver Province newspaper on Monday, March 17, 1952.

Retarded Children To Be Aided By Newly-Formed Group Here

The newly formed Association for the Advancement of Retarded Children held its first party for the children recently with great success.

This party and plans made for the future by the association reveal a different and optimistic outlook on a problem which has until recently been kept from the public eye.

Parents have been made to believe that backward children should be kept either in semi-isolation in their own home or in an institution.

Some, having refused to accept this answer, are planning an extensive program to prove that these children can be helped.

Members of the association are working on an educational centre to care for the physical, mental, and social development of retarded children. Parents are planning a school.

Mrs. J. Purdy, president, and Mrs. W.A. Rogers, convener made arrangements for the party for the retarded children. Those interested in the association, either wishing to assist it or use it as a benefit to themselves, are asked to call Mrs. H.A. Winter, secretary, at KE 0092L.

In April, 1952, the Association’s first public meeting attracted fifty people at which time a constitution was drawn up and the decision to organize under the Societies Act was made. Further discussion centred around the proposed day school. A suggestion was made that the school should begin with a pilot group of six pupils to ascertain the direction to take in the development of skills and routines. Disagreement arose, however, over whose children should comprise this pilot group.

The first day training class began in Knox Church Hall in May of that year with an enrolment of 24 pupils. Because the class lacked a qualified teacher, Mrs. Purdy became the chief organizer of the program. The parents were organized to provide supervision, training, and transportation. The open door policy of the school was dropped when workers during the first week found themselves unable to handle some of the pupils. Thereafter the school sought to screen pupils for possible acceptance into the school.

In September, 1952, classes were moved to St. Michael’s Church Hall, a more central location. Pupils from the west end of the city attended on Tuesdays and Wednesdays while those from the east end attended on Thursdays and Fridays. This arrangement offset the problems caused by the school’s lack of sufficient equipment, proper facilities, and volunteer staff. Parents paid $6 per month towards transportation costs while the Vancouver School Board supplied some of the handwork materials used. The response of the School Board to act in this minor way was the result of a heart rending plea on behalf of retarded children made before the trustees by Mrs. Purdy.

By the spring of 1953, the Association was in need of more financial assistance and sent a delegation to Victoria headed by Mr. Moore and Mrs. Purdy. The group conferred with the then Provincial Secretary Leslie Black, and the Minister of Education, Tilly Rolston. They became the first group of parents of retarded children to request such aid for their retarded children. Although the Government gave the delegation a very sympathetic hearing and a grant-in-aid of $2000 from the Provincial Secretary’s Department, it remained in a quandary as to what department should handle the problem of a day training school. The choice lay in either the Department of Health and Welfare and the Department of Education.

The growth of the organization and the school during 1953 was beginning to demand so much of Mrs. Purdy’s time that the membership provided her with a salary and made her the Executive Director. A few members were very much opposed to hiring Mrs. Purdy, feeling that the school would benefit more if a teacher were hired first. However, these feelings were eased later in the year when the Junior League gave the Association a grant of $1500 towards the hiring of a qualified teacher. This amount was increased to $2000 the following year.

Additional aid from other service groups was sought by Mrs. Purdy. Her considerable speaking ability put her in demand both in and outside of Vancouver. As a result of her efforts, contributions were received from the Discus and White Cane Clubs, Council of Women Toast Mistress Clubs, Salvation Army, as well as employee groups from local firms. And the Lions and Kiwanis clubs played an important role in meeting transportation and equipment needs.

The continuing program of public relations led Mrs. Purdy to speak to groups in Victoria, Chilliwack, Nanaimo, Abbotsford, Powell River, and New Westminster. By 1954, associations for the retarded which had incorporated in these outlying areas also began to request government aid. Some embarrassment was evident among Government officials as delegation after delegation began to arrive. It was felt that Government embarrassment was due to its failure to set up a proper committee to investigate the problem of retardation following the visit of the Vancouver delegation in 1953.

It was at this time that Dr. Donald Patterson from the Crippled Children’s Registry called together Dr. Dunn and Dr. McCreary of the School of Medicine, U.B.C., Dr. R. Sharp, Superintendent of the Vancouver School Board, and Dr. Murray of the Medical Health Office in Vancouver to find out what was being done for retarded children in the city. This meeting put impetus behind Mrs. Purdy’s known desire to have a provincial organization for the retarded established. It was thought that this larger body would have a stronger voice in seeking Government recognition and aid for the retarded. But it was not until 1955 that such an association was officially formed.

Pressure exerted on the government in 1956 by both the local associations and the newly formed provincial body finally resulted in an amendment in the Public Schools Act. The amendment, in the form of Bill 68, was significant in that it was the first official recognition of the need to assist in the education of the retarded. The Bill reads, in part, as follows:

“The Board of School Trustees of a school district may pay to the Association for Retarded Children of British Columbia an amount of money towards the cost of education and training of any mentally retarded child normally resident within the school district who is authorized by the Board to attend a special school operated by a chapter of, or an organization in affiliation with, the said Association and operating under regulations prescribed by the Council of Public Instruction. Such a payment shall be made in accordance with regulations prescribed by the Council of Public Instruction, and shall form part of the approved operating expenses of the Board, referred to in Section 20, to an amount not in excess of the net operating cost of education per pupil on average daily attendance in the schools of the Province as stated in the latest published Annual Report of Public Schools of the Province of British Columbia.”

The grant amounted to $256.47 per pupil and the immediate effect of the grant in the Vancouver school was an increase in its enrolment. Bill 68 also made it possible for School Boards to establish liaison with Association schools in their districts. The Vancouver School Board responded immediately by appointing Dr. S. Miller to the Association’s Screening Committee and later formed an Education Committee which was composed of Dr. Miller, G. Atherton, E. Bjarnason and W. Rogers. The latter three represented the Association.

Additional school facilities were acquired by the Association for thirty senior students in January, 1957.At first, the group used the Hastings Community Centre but later moved to the Kimount Boys Club, the latter being more centrally located.

To stimulate further public interest in the school, a monthly open house program was instituted in the fall of 1957. Parents were encouraged to invite their neighbours to attend and Mr. Bjarnason, president of the Vancouver Association, used this opportunity to acquaint officials of the School Board and the Provincial government with the operation and needs of the school. The specific need for improved facilities was uppermost in his mind and he, along with a majority of the Board of Directors, were convinced that such facilities would ultimately have to be provided by the School Board. They were also convinced that eventually the School Board would have to assume full responsibility for educating the retarded. Differing opinions were held by Mrs. Purdy and by other charter members. They could see that the Board of Directors’ objective would eventually be reached, but because they had done so much in getting support from service clubs and in organizing the school program, they were not ready to relinquish control. Regret over increasing control by others in the Association finally led to the resignation of Mrs. Purdy as Executive Director in March, 1958. The tension over this issue never reached the membership for it was Mrs. Purdy’s belief that public knowledge of tension within the Association would only jeopardize the good image already established by the school.

Some controversy also existed between the B.C. Association and the Vancouver Association regarding Vancouver’s objectives. In the minutes of the B.C. Association meeting of November 16, 1957, W. Goepel, the Executive Director, made the following remarks which indicate the controversy:

“Recently at an informal meeting with the Minister of Education, we were informed that two or three of our Chapters have made representation to the government (presumably informally as no application went through the formal channels of the B.C. Association), for financial assistance in building schools for retarded children, and that these Chapters (or their representatives) had been very definite in their assertions that retarded children can never be integrated into the public schools system, but must always have special facilities to segregate them from the normal. The Minister pointed out that this theory is quite contrary to the request contained in the brief presented by the B.C. Association last April. Do you want them segregated from the rest of the community?

On the other hand, if the education of retarded children is taken over by public authorities, our Chapters would have to relinquish operation of the classes, teachers would have to meet Department of Education standards, and children would presumably be required by law to attend school.”

In these same minutes, Dr. Gee, Director of Mental Health Services and adviser to the B. C. Association, advised local Chapters,

“to work closely with their School Boards, to utilize existing school facilities wherever possible, and to keep hammering at the Department of Education until they do fully accept the responsibility for the education of the retarded …”

When an effort to gain Red Feather support failed in the fall of 1957, a joint committee was formed by the Vancouver Association with Kiwanis Club representatives in an effort to improve school facilities. The Kiwanis group came to realize that educating retarded children was more than private groups could handle financially. (There were fifty-two pupils at St. Michaels and the Hastings Community Centre at this time.) Subsequently, a Kiwanis delegation presented a brief to the Board of School Trustees requesting that the Board provide facilities for 100 retarded children. The trustees stated that it would require an amendment to the Public Schools Act for the Board to build the school, but a special committee was formed to discuss the issue with the delegation.

In speaking to a meeting of the Association on May 29, 1958, Dr. E.N. Ellis outlined the work and findings of the Educational Committee and the direction the School Board was taking. However, the B. C. Association was still concerned over the Vancouver School Board’s impending course. On May 27, 1958, the Board authorized a delegation to go to Victoria with a brief stating their willingness to assume responsibility in the field of retardation as legal moves by the governments make it possible.

The brief from the Vancouver School Board was followed by one submitted by the B. C. Association supporting Vancouver’s proposal as well as the interests of outlying areas. The Government made no assurance at the time of these presentation s as to how soon it would act. Their decision to make an amendment in 1956 to the Public Schools Act was favourably influenced by the fact that Ontario had already introduced a system of grants towards Chapters for the retarded. A further change in. the Act as suggested in these new briefs would set a precedent in Canada.

Not knowing how the government would respond to the briefs, the Vancouver Association continued to look for additional facilities for their school. The School Board first offered them Norquay Annex. However, it was turned down because it lacked washroom facilities and was not at ground level. Vacant land across the street prompted a further offer by the School Board which would have given the Association another school, Moberly Annex A, to place on the land. The only problem was moving this annex to the vacant lot. The expense of moving the annex was beyond what the Association could raise. Further efforts to provide additional facilities were not made until after the 1959 Session of the Provincial Legislature.

At this Session, three more amendments to the School Act were passed.

“They first increased the grant per pupil by fifty per cent; its immediate effect being an increase from $262.60 per year to $393.90. The second empowered school boards to provide school accommodation for pupils in schools operated by local chapters of the Association. The third empowered a school board with the approval of the Minister of Education and in compliance with appropriate Rules of the Council of Public Instruction to establish and maintain special classes within the public school system for the education and training of retarded children.”

Following the Government’s decision, the Vancouver School Board announced that it would renovate a four room building at Sir Sandford Fleming Elementary School at a cost of $10,719. in an effort to provide temporary classrooms for the Association ‘s school. These facilities were ready in September, 1959, at which time eighty pupils were enrolled and research was begun on plans for a separate school immediately.

A referendum to provide the necessary $240,000 for the new special school was passed on December 9, 1959. Public interest and support was sought prior to the vote in order to gain the necessary majority. For example, the support of the Parent-Teacher groups in the city was secured by the Association’s soliciting their help as volunteers in the school.

A Government freeze on school construction delayed plans at first, to the point where School Board officials were ready to put off the project indefinitely. However, a personal loan of $240,000 to the School Board from store-executive, P.A. Woodward, enabled the school to be built without too much delay. The school, now named Oakridge, was officially opened on May 12, 1961, with an enrolment of 113 pupils. It was Canada’s first school for retarded children to be built and administered under a public authority.

It is interesting to note that a few parents of pupils in the school were very much afraid of the consequences of having the school administered by the School Board. They felt that their children, because of their lack of progress up to that point, would be screened out of the new school. The opposite became true, however, as many who were screened out before because of lack of facilities and qualified teachers were enrolled in the new school.

It could be said that the need to provide day training centres like Oak ridge has existed since the society first demanded public education for all of its members. However, only a changing social philosophy, more accepting of this group of handicapped children, has allowed for appearance of such training schools today. To hide retarded children in homes or institutions is now considered archaic and inhumane.

The Vancouver School Board gave its whole-hearted support to the Association’s school, where legally possible, from the start. But an underlying reason for the initial support conceivably could have been because such endorsement did not constitute any financial commitment. The problem of why public intervention did not occur before 1956 with the first change in the Public Schools Act, lies with the Provincial Government and in particular with the Department of Education. Although the Department of Education started to do research into the education of slow learners in special classes in 1935 and had shown responsibility towards them since 1913, the trainable groups were never investigated as to their educational worth. The Government could possibly have acted sooner had such research been carried out.

The Vancouver community gained in a social sense by having the school begin under private auspices. The service groups and private citizens introduced to retardation through the activities of the Association experienced many changed attitudes with respect to the acceptance of these children. Such awareness and acceptance by the community probably would have come more slowly had the government made the initial move…

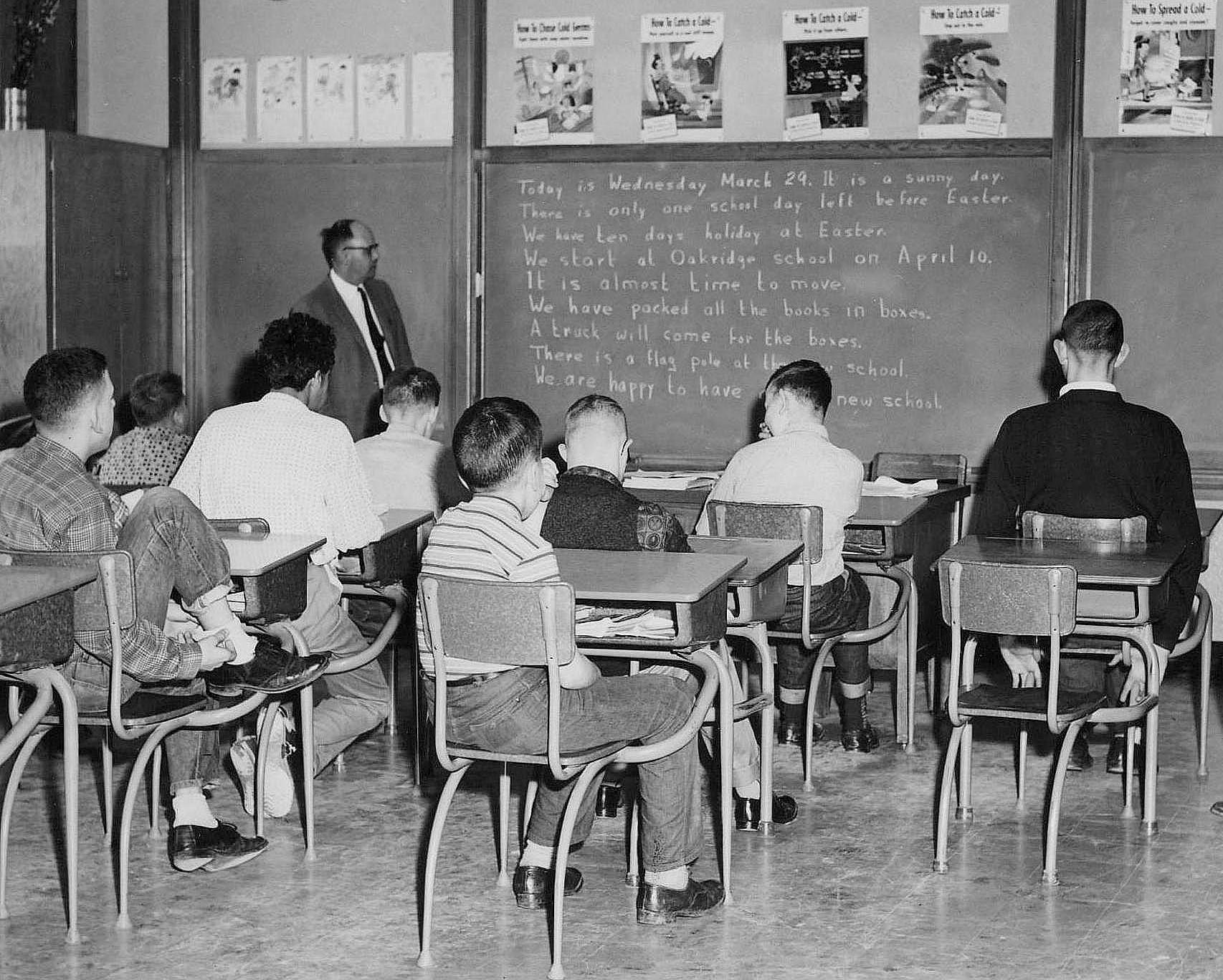

PHOTO GALLERY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Johnson, F.H., A History of Public Education in British Columbia, University of British Columbia Publications Centre, Vancouver, 1964.

- Report, Federal-Provincial Conference, Mental Retardation in Canada, Department of National Health and Welfare, Ottawa, 1965.

- Briefs to B.C. Government,

Vancouver School Board, 1958. Association for Retarded of B.C., 1958. Association for Retarded of B.C., 1959.

- Files on Education and Screening Committee, Vancouver School Board, Department of Research, 1956 – 1960.

- Manual of The School Law, Province of B.C., 1961.

- Minutes of Directors Meetings, Association For Retarded of B.C., 1957 – 58.

- Interviews

- A. Buck, Principal of Oakridge School, Vancouver, B.C. Mrs. E. Dickson, teacher, Vancouver, B.C.

- E.N. Ellis, Vancouver School Board, Vancouver, B.C. Mrs. J. Galbraith, Vancouver, B.C.

- S. Miller, Vancouver School Board, Vancouver,

- C. Mrs . E. Morris, teacher, Vancouver, B.C.

- J. Purdy, White Rock, B.C.

- Wiginton, Vancouver Association for Retarded, Vancouver, B.C.

A P P E N D I X

UPDATE TO “THE HISTORY”

All the hard work described in the foregoing pages has created Oakridge School, Vancouver’s school for mentally retarded children, operated by the Vancouver School Board.

Today, our purpose at the school is to take children who are non educable and train them so that they may become socially acceptable in the community and as economical ly useful as possible at home, in a sheltered workshop, or some other carefully supervised environment. Children are accepted at the age of six years and are kept through the school year in which they become nineteen.

THE SCHOOL IN 1976

The staff consists of a principal, vice-principal, sixteen regular classroom teachers, six staff assistants, a secretary, a part-time medical health officer, a nurse, a part-time school psychologist, and one supervision aide.

Normally there are twelve children in each of the following classes: Senior boys, Senior girls.

Intermediate boys and girls Junior boys and girls Primary boys and girls.

Primary boys and girls (this class includes beginners without any group experience).

Although a child is assigned to one particular group, the school program is such that he comes in contact with other children and teachers throughout the day. Classes combine for music, games, folk dancing and other activities. Assemblies are held regularly to give training and experience in an audience situation. A full-time P.E. and swimming program is in operation which includes pupils of all ages and a Learning Assistance Centre is in operation for pupils who can benefit from extra help.

CENTRAL SCREENING COMMITTEE

The Central Screening Committee for admissions to Oakridge School is composed of nine members, including the Director of Mental Health Services (Vancouver Health Department); Head of Student Services, and Senior Coordinator of Special Education (Vancouver School Board) and the principal of Oakridge School.

METHOD OF PROCEDURE FOR ADMISSION

Parents who reside in the City of Vancouver and have enquiries about admission to Oakridge School should first bring their child to the Vancouver School Board office for a psychological examination. If the child has a mental capacity incapable of development beyond that of a child of normal mental capacity at 8 years of age, and if the child is recommended for training, the parents should then get in touch with the Health Unit in their district and make an appointment for a medical examination. In the event that psychological and medical reports are favourable, the child is accepted by the Screening Committee for admission to Oakridge School. Some children are admitted on a trial basis.

SOME OF THE MORE SPECIFIC AIMS OF OAKRIDGE SCHOOL

- To help the chi.Id make a successful adjustment between home and school.

- To help the parent accept his child’s limitations and build on his abilities.

- To develop the child’s confidence and self-expression.

- To teach the child to speak as clearly and correctly as possible while increasing his vocabulary.

- To train the child in the recognition of words and numbers that will be useful to him in his everyday life.

- To develop optimum personal happiness within the limit of the child’s capabilities.

SCHOOL FUNCTIONS

It is the aim of Oakridge School to have all pupils participate to the limit of their abilities in functions such as those carried on in a school for normal children. To this end, the school program has included such successful and orderly projects as: Open House, Sports Day, Swim Program, Christmas Programs, Coffee Party & Fashion Show, Tobogganing.

Regular Friday morning assemblies which provide valuable experiences in: 1)audience situations 2) sitting attentively and quietly 3) developing a feeling of school spirit 4)meeting new people and 5)visual education.

TRANSPORTATION

Transportation is a major problem for this type of school. Our pupils are transported by bus from all parts of the City of Vancouver at no cost to the parents . The finances are arranged by the School Board. A number of pupils travel by public transportation.

The children arrive by 9:00 a.m. by bus and go directly to their individual classrooms. At 2:00 p.m. all pupils go to their respec tive “Bus Rooms” – each bus load meets in an appointed room. The children are checked by a teacher on duty, called for by a driver, and then taken to their correct bus. This routine is a part of the training program.The majority of the pupils can be relied upon to go to their proper rooms and get on the right buses.

In line with all routines in a school for retarded children, simple explanations, repetition of program and careful supervision help to develop desirable behaviour patterns.

THE FUTURE

The question which is most frequently asked is, “After Oakridge School – What?”In a high school there is, to a limited extent, a familiar problem – as shown by many studies of post-graduate students. The following seems to be a fair prognosis of our “Graduates” :

- Some will fit into a sheltered workshop or similar sheltered work experience.

- Some will remain at home to help with home duties.

- Some may be residing in an institution but presumably will require less custodial care than those who have not had school experience.

- Some may be gainfully employed in repetitive, routine type jobs.

We feel that whatever his placement, the individual who has had the advantage of group and individual training at school, will fit in better and feel happier in his environment than the child who has had no formal training – and thus prove to all that “RETARDED CHILDREN CAN BE HELPED”.