French Immersion

This Feature focuses on two components of schooling in the French language: French Immersion for non-French speakers and schooling for French speakers

I. FRENCH IMMERSION

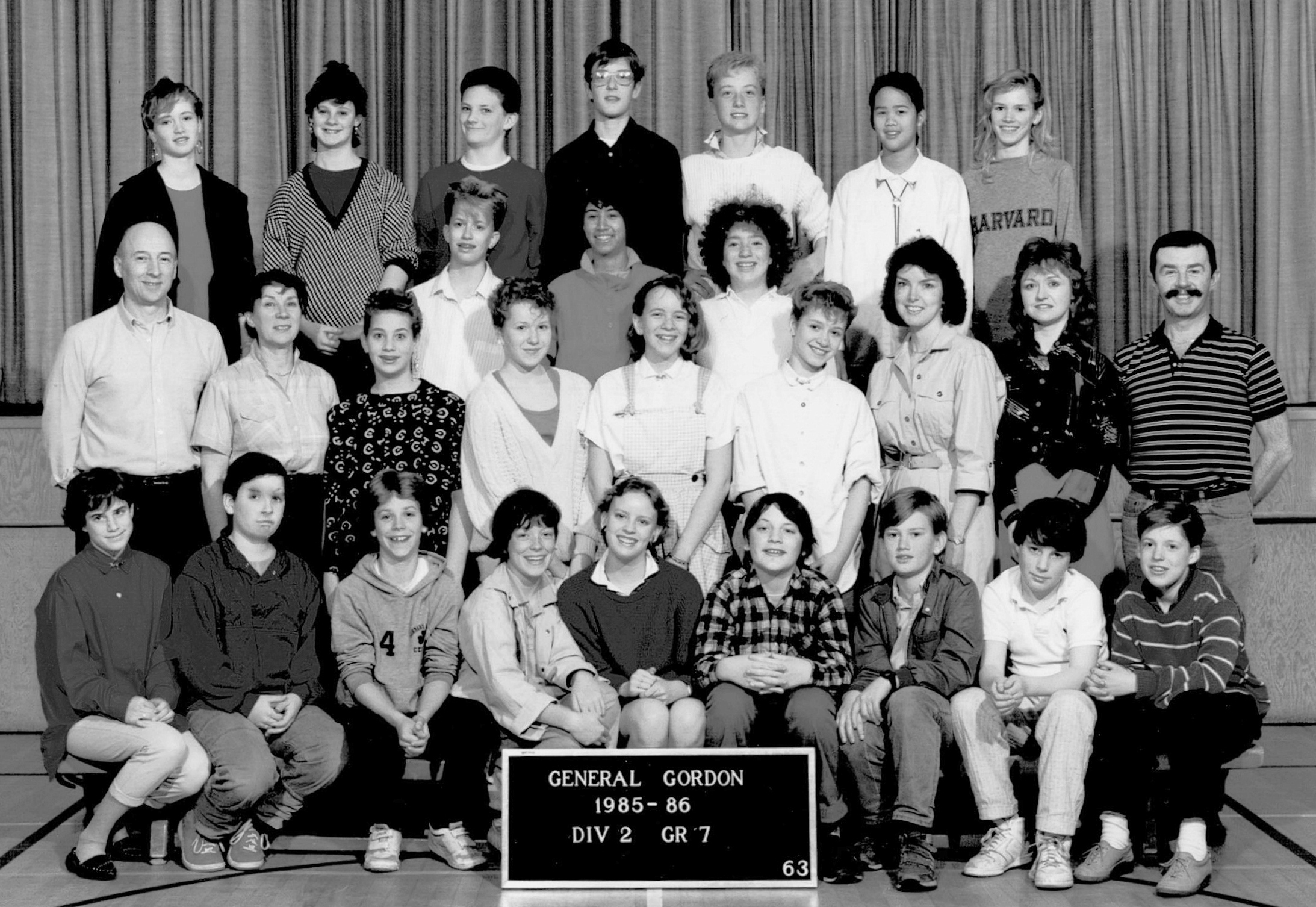

General Gordon Elementary Staff Photo (1986) – the school became home for a Late French Immersion Program in the Vancouver School District beginning in the 1980s

FRENCH IMMERSION PROGRAMS IN CANADA

(The following is excerpted from a post on the CBC website)

Ayesha Barmania, Cross Country Checkup – CBC. Posted: Jun 11, 2016; Last Updated: March 12, 2017.

Time and again, Canadians have encountered a sticky debate about bilingualism and French instruction in schools. In the 1960s we asked: should French be an official language, equal to English? As French became increasingly valued by Anglophones, the question became: what’s the best way to learn French? And now, on Checkup we’re asking: Have French Immersion programs for school children lived up to their promise? Below we track the evolution of the debate and a tug-of-war between Anglophone and Francophone interests.

- French immersion was first developed in Quebec during the 1960s, in the midst of the province’s “Quiet Revolution”.

It was a time when Quebecers were dealing with swath of social issues, and chief among them was education. There were a series of reforms geared toward improving the quality of French education, by transferring control from the Catholic Church to the provincial government. As this was happening, Anglophone parents started becoming concerned that their children were not learning French well enough in an English school. After many meetings and consultations, French immersion was born.

- Should French be an official language, equal to English?

For six weeks in 1964, the Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism toured across Canada to hear what Canadians thought of official bilingualism. For many English speaking Canadians, French was irrelevant and a nuisance. But for many others, recognition of the French language was welcome. One woman who spoke at the commission said, “Some people think that bilingualism is good for nothing, but [I say] why shouldn’t we learn all the languages that we can? It just makes us smarter.”

The commission issued its final report with the recommendation that all government business be offered in both English and French. One year later, in 1965, the Official Languages Act was tabled by Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau. This resolution would make both English and French official languages. (The Official Languages Act passed in 1974.)

- How well did French Immersion students like their education?

In a documentary for the CBC Radio program Sunday Morning, principal of Sacre Coeur School, Sister Dumesnil said, “In 1973, all youngsters whose parents wanted to them in an immersion program registered them in this school. They came from all over the city of Winnipeg. Since then, it has certainly mushroomed around us.”

- Support for French Immersion

“Statistics tell us that French immersion programs are dominated by students from families that are well-educated and have higher income. There are fewer boys and fewer kids with special needs. It seems evident that some of the advantages of French immersion [are] based on the fact that it’s more exclusive.”

- Opposition to French Immersion

While French immersion was gaining support amongst Anglophones, Francophones were unhappy with their lot. In a subsequent documentary from 1988, Francophones in Alberta expressed their dissatisfaction with a school system that put their French speaking children in an English system they deemed inadequate to meet the needs of children whose mother tongue was French. Without a dedicated French system for high school, Francophone students were channeled into the English system’s French Immersion….

FRENCH IMMERSION PROGRAMS IN THE VANCOUVER SCHOOL DISTRICT

(The following is taken from the Vancouver School Board website)

The Early Immersion program provides at least one-half of the school day in French-language study for the full seven years of the Intermediate Program (grades 4-10). The subjects taught in grades 8-10 are a natural continuation of the child’s elementary experience allowing to students maintain and extend their expertise in French in a way they cannot do in other programs.

The Late French Immersion students take an identical program of studies in the secondary years as their Early Immersion counterparts. Beginning in grade 11, the amount of time in French is further reduced by one-half. This arrangement enables the students to pursue specialized courses to meet post-secondary requirements. Then, in grade 12, a further reduction in time spent in French occurs. Francais 12 permits the Immersion students to maintain their French proficiency in their final year of school.

Elementary Programs

The Vancouver School Board’s Early French Immersion program accepts 5 and 6-year-olds at the beginning of their formal schooling. This program is intended for non-French speaking students who wish to develop a high-level of proficiency in both official languages.

The BC curriculum is instructed in French from kindergarten to the end of Grade 3. From Grades 4-7, 50 to 80% of the BC curriculum is taught in French.

Although the common point of entry to Early French Immersion is kindergarten, Grade 1 students may enter up to September 30th if space is available.

Early French Immersion Schools

- Hastings Community Elementary (K-7)

- Henry Hudson Elementary (K-7; no kindergarten enrolment from 2020)

- Ecole Jules Quesnel Elementary (K-7) French Immersion ONLY

- Kerrisdale Elementary (K-7)

- Laura Secord Elementary (K-7) Early French Immersion K-7 and Late French Immersion 6-7

- L’Ecole Bilingue Elementary (K-7, French Immersion ONLY)

- Lord Selkirk Elementary (K-7)

- Lord Tennyson Elementary (K-7) French Immersion ONLY

- Sir James Douglas Elementary (students go to Sir James Douglas Annex for K-3, Sir James Douglas Elementary for 4-7)

- Queen Elizabeth Annex (K-3) (students go to Ecole Jules Quesnel Elementary for 4-7)

- Quilchena Elementary (K-7)

- Lord Strathcona Elementary (K-7)

- Trafalgar Elementary (K-7)

Late French Immersion Schools

- General Gordon Elementary (grades 6-7)

- Laura Secord Elementary (grades 6-7)

Secondary Programs

- Churchill Secondary

- Kitsilano Secondary

- Van Tech Secondary

Recollections of the Early Days of French Immersion at General Gordon Elementary, Vancouver School District

A FIELD TRIP

by Georgette Grant

I scan through snapshots of my grade 7 class of 1985, and their names pop into my head: Karen, Matthew, Leslie, Matt, Fenton. Bright shiny faces, full of mischief. I had had no idea when I walked into the job how unusual a teaching situation it was: it was Late French Immersion, the first of its kind in Vancouver in the early 1980’s, though Early Immersion was already well established.

Late Immersion students started the program in grade 6, transferring from the regular English stream after applying at the end of grade 5. They knew, and their parents knew that they would have to hear and speak only French during their grade 6 year, with only one class, Music, to be given in English.They were there by choice, a joint decision made with their parents. In grade 7 they would have one more class in English, that is, English, known as Language Arts. If all went well, they’d move on to an Immersion high school, where they’d blend in successfully with the early immersion students.

For the teachers in Late Immersion, it was a golden age. There was “start up” funding from the federal government, so we had the luxury of time to build the curriculum, plan special events, make decisions about books, and fill the library shelves. As there were two immersion classes at each grade level, 6 & 7, we were able to platoon: in my case, that meant I could teach the two English classes and leave the Math to my colleague, Jean-Claude, who spoke very little English. He taught my Art; I taught his Phys.Ed. A third teacher came in to do Science, les sciences naturelles. We had a full time French teaching assistant originally from Lyon.

The support, the extra time, and the teamwork were all unusual and wonderful, nothing like the routine of most elementary teachers. At that time they had only 2 prep periods of 40 minutes per week; otherwise they worked with large classes of students all day, teaching every subject except music. As you can imagine there were tensions between the regular teachers and the new “stars” who took the best students and swanned around the school speaking French and leading delegations of visitors keen to observe the new late immersion.

To some extent we performed in a fish bowl. We felt the pressure to succeed all the more as we knew that our grade 7 graduates would have to blend in successfully with Early Immersion at the high school level. But all the while we felt challenged and respected and exhilarated, almost every day.

In 1985, my third year at General Gorden, we set up a grade 7 Exchange with two classes from Quebec. The students were be matched, or twinned, with a francophone student from Lauretteville, Quebec. They’d introduce themselves with a letter and photos, and then eventually be billeted with their twin’s family. Jean-Claude and I, together with our assistant, planned and organized the trip, trying to foresee every eventuality.

The previous year the parents of one of our students had sued the School Board because their son had fallen off the trolley in the school yard and broken his arm. I was on supervision when it happened and was named in the suit. I hadn’t witnessed the accident, but I had to answer questions at the formal Examination for Discovery. “Should I not have realized that the trolley was unsafe? Should I not have brought this to the attention of the administration?” It was hard not to take this process personally. The parents and the Board ended up settling out of court, and the boy continued in the program. He was now going to Quebec with us. So we had many reasons to plan carefully.

The trip took place in March. A small glitch occurred at the Vancouver airport: our flight was delayed for some reason, and we waited something like 6 hours before taking off. The kids were in high spirits, not daunted in the least, and I could see there were a couple of characters to keep in my sights at all times. A pair of inseparable boys, one who idolized the other and was easily led.

We arrived at our destination late in the evening after a bus ride to the suburb of Lauretteville on the outskirts of Quebec City. We were greeted enthusiastically; the kids went home with their billets; teachers retreated to hotel rooms, relieved and exhausted. During the day we toured the sights, sometimes with our own students, other times accompanied by the Quebecois classes. The first surprise to me was that there was another BC school participating in the exchange at Lauretteville at the same time. Altogether there were six classes. This made crowd control a little tricky, especially when we went out in busloads. As well, the Quebecois style was more laissez-faire: their students were on a first name basis with teachers and behaved more like friends and equals. It seemed to work for them.

Jean-Claude and I remained M. Lamontagne and Mme Champion.We visited the gothic basilica of Ste Anne de Beaupre with our classes alone. We toured the various chapels along each side of the sanctuary. Inside one the chapels there suddenly appeared an intruder: one of my inseparable boys, posing like a stature and leaning his butt on the small altar. Although our preparations had involved endless discussions about rules of behavioral, we had failed to mention how to behave in a church.

One day the six classes piled into buses—students in mixed groups, along with their twins, and random teachers. We headed for the famous waterfall of Montmorency. I was on the third bus to arrive at the site. As I looked out the bus window, I spotted the two inseparables at the head of a group, racing across a field of snow toward the falls. I asked my Quebecois colleague what was under the snow. She replied, “Ben, le lac.” Lake Montmorency. Did I mention that although the weather was chilly, it was raining. I had visions of students falling through the ice.

I rushed out in a panic, calling to the two leaders, my boys, gesturing for them to return. They turned and saw me, cheerfully waved and yelled back “Bonjour Madame!” Had they misinterpreted my gesture? Unlikely but possible. I decided in a flash that if a student went through the ice I was going with him. I took off across the field. Meanwhile one of them had climbed on top of what looked like a small hill of frozen foam, bound to collapse. I plunged ahead, cursing my high-heeled boots.

Well, I guess the Quebecois teachers knew something I didn’t. No doubt the ice beneath the snow was thick, though the snow was melting all around us. We all survived.

PHOTO GALLERY

II. SCHOOLING FOR FRENCH SPEAKERS

Public French schooling was established by the Government of British Columbia in 1977. Known as the programme cadre de français, this program was managed by a number of English first language school boards in British Columbia, including the Vancouver School Board. In 1983, in Vancouver, British Columbia’s first homogeneous Francophone public school opens: Ecole Anne-Hebert in Vancouver.

In 1995, the provincial government established a French first language school board, known as the Francophone Education Authority, which provided French first language schooling for residents residing in Chilliwack and Victoria. On July 01, 1999 new legislation went into effect which expanded the school board’s jurisdiction to cover the entire province.

This is how the Francophone Education Authority describes itself in a posting on Wikipedia:

The Conseil scolaire francophone de la Colombie-Britannique (also known as Francophone Education Authority or School District No 93) is the French-language school board for all French schools located in British Columbia. Its headquarters are in Richmond in Greater Vancouver. Unlike the other school boards in British Columbia, this school board does not cover a specific geographic area, but instead takes ownership of schools based solely on language.

The school board helps ensure those with constitutional rights to minority language education under section 23 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms receive it.

The Conseil scolaire francophone de la Colombie-Britannique offers educational programs and services geared towards the growth and cultural promotion of the province’s Francophone learners. An active partner in the development of British Columbia’s Francophone community, the Conseil has presently in its system, and distributed across 78 communities in the province, over 5,700 students and 40 schools. The school board also operates a French first language virtual school known as École Virtuelle.

Copyright © 2026 | MH Magazine WordPress Theme by MH Themes