City School – A History

CITY SCHOOL – A HISTORY

by Sal Robinson

Beginnings

In the latter half of the 1960s, with independent alternative schools on the increase, the Vancouver School District began offering differently structured programs at some elementary schools (“Major Works” classes in 1966) and in some secondary schools (“Integrated Programme” at Point Grey and ”S.E.L.F.” at Prince of Wales and Lord Byng in 1968).[1]

The first stand-alone public alternative school in Vancouver would be City School, the brainchild of Dr. Alf Clinton, VSB’s Director of Education. What follows is the proposal he presented to the trustees.

A Proposal For An Ungraded Continuous Progress School (City School)

The City School Project is designed for students whose educational growth requires experiences beyond those to be found within existing school programs. These students, ranging in age from 10 to 15 years, will come from all the city’s attendance areas; each will enter the program voluntarily. Similar projects have been successfully implemented in other urban areas with two of the more notable being the Metropolitan Learning Centre, Portland and the Parkway Program, Philadelphia. Following is an outline of the project’s aims and method of operation, designed to facilitate planning for its implementation in September, 1971:

Aims for Students

All students have a need to gain experience in making real decisions affecting their lives and in learning to cope with the frustrations of life in the world outside the classroom. In City School each student – in consultation with staff member, other students, parents and community resource people – will design, carry out and evaluate his own learning program. The entire resources of the metropolitan area will be considered potential for the learner to create a meaningful program to meet his own needs. For many this will not be an easy process. However, by having to decide what he wants to learn, through finding out how and where this can be done, by sharing his experiences with others, and by evaluation of his efforts, each learner should develop habits and skills which may better enable him to continue learning throughout life. The City School experience is designed to develop a healthy sense of responsibility for one’s actions and for the community through active involvement in it.

Aims of Curriculum

The curriculum will focus on the development of a sound General Education program. The objectives of this program will be to provide students with a base of knowledge that is useful in life; to help them see relationships between events and the contemporary world, and to provide them with the skills to identify and solve problems confronting them, now and in the future. Within the framework of this General Education program, students will be helped to gain proficiency in the communication and computational skills.

The program will offer an ungraded, interdisciplinary approach designed to give students the core content of required courses in English, social studies, mathematics, science, physical education and the arts. This approach will be radically different from that practised in conventional classrooms, and will cut across traditional grade barriers which will enable greater articulation between all age levels. For example, rather than engaging in systematic study of the various disciplines, the student will focus on the solution of problems more relevant to his needs. To solve these problems, teachers and students will plan together and the curriculum will be developed through emphasis on the learning process rather than the teaching act. Also this emphasis will enable older students to work with younger students.

Method of Operation

Enrolment of no more than 100 students is planned for the first year of operation of the school. Later it is anticipated that the enrollment will increase to a limit of approximately 150 students, K – 12. The staff – a team of four teachers – will function under the coordination of a VSB Education Department official who will be responsible for carrying out overall policy and evaluation of the program. Policy within the project will be determined through interaction among students, staff, parents and community participants.

While much of the education will occur throughout the community, a central base is required. Edith Cavell Annex is recommended as this base, because of its proximity to the business and cultural heart of Vancouver and its central location for transportation purposes.

The regulations of City School will be simple. Students will be asked to work together congenially, to follow agreed procedures of daily accountability in developing and working out their individual programs, to record and evaluate their learning experiences and to attend on a regular basis.

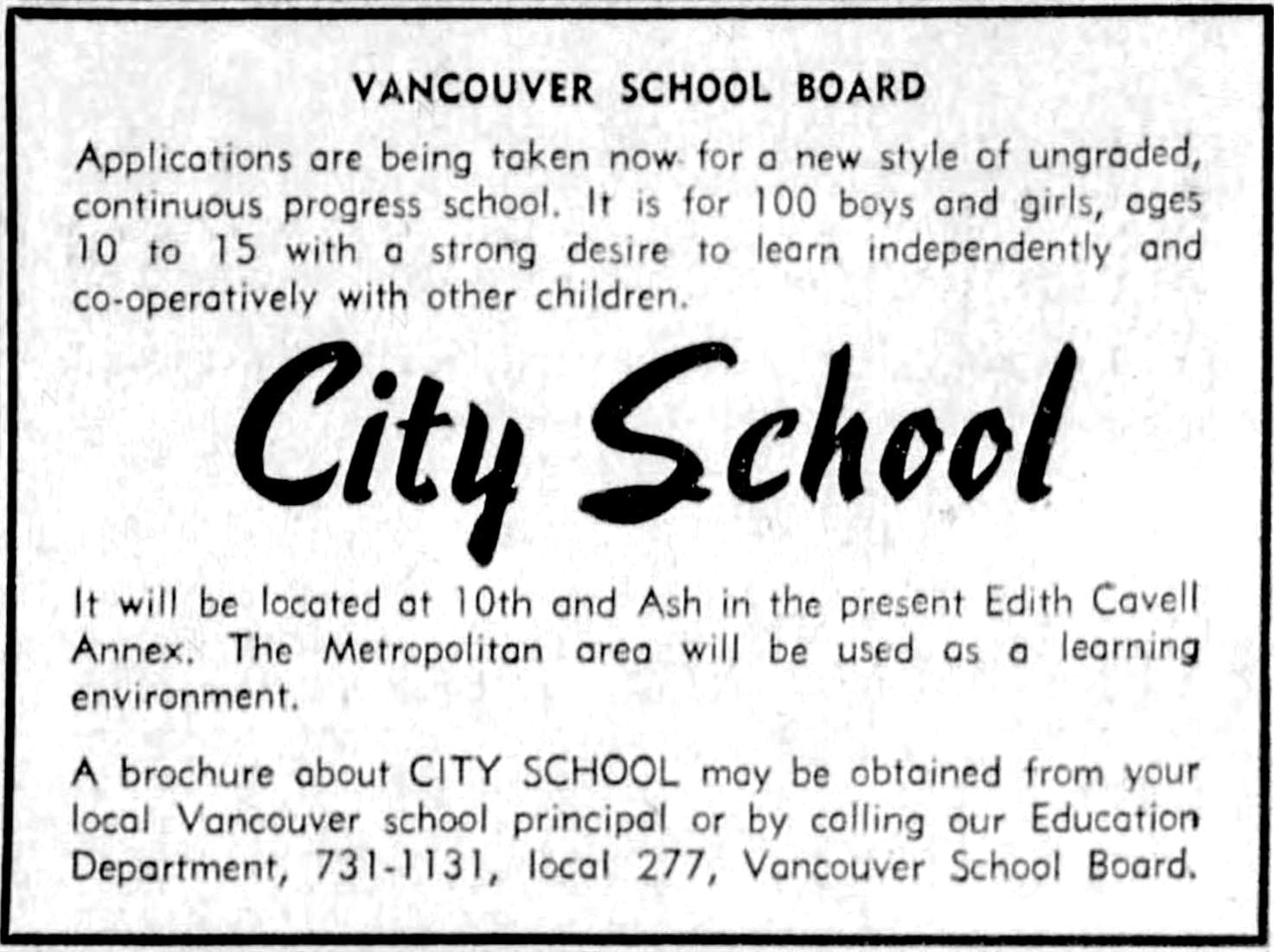

Dr. Clinton’s proposal was accepted and by June of 1971, local newspapers were providing publicity with articles headlined, “Ungraded school for city scheduled to open in fall”[2] and “New school strides into the future: Student participation comes to Vancouver”[3]. Advertisements directed interested parents to get brochures from their local school. More articles appeared in the summer: “Experimenting in school”[4] termed City School “a bold innovation” that might sound “way out.”

from June 12, 1971, The Vancouver Sun

Part I – September 1971 to June 1974

City School opened on September 7 and was in the media cross-hairs the next morning. An editorial titled “Back to school, with a difference…” cautioned,

“Mention of free schools may strike fear into the hearts of many, perhaps most, parents who may see visions of their children turning out vacuous, unmotivated ne’er-do-wells and misfits. And there is the legitimate fear that educational experiments may leave those taking part in them worse off than if they’d been given the standard schooling.”[5]

A much more positive picture was painted later in the month when reporter Wilf Bennett visited City School in the former Edith Cavell Annex at 550 West 10th Avenue and wrote about what he found.

“The city’s newest school – simply called City School – has no principal, no regular classes, no exams, no formal structure of any kind. Since it opened on Sept. 7 the 100 students have decided each morning what they want to do during the day. Suggestions come from the pupils themselves and from the school’s four co-equal teachers. The day’s options are outlined on a big blackboard in the entry hall and the youngsters then decide which they will follow for the day.”

Bennett described some of the activities: studying poetry, collecting science specimens and making art in Little Mountain Park; cooking and eating a chicken and inspecting its head preserved in formaldehyde; touring VGH; visiting a veterinary clinic and watching an operation on a dog. He also commented on the students.

“The children are prolific with the flood of ideas about things they want to see and learn about, the teachers say. What children attend City School? The 100 come from all parts of Vancouver drawn by lot from nearly 200 who applied to attend it rather than their own neighbourhood schools.”[6]

City School was established with students aged 10 to 15 and the intention of expanding to include the primary grades while advancing the initial group – and taking on more senior students – through to Grade 12. The expansion to include younger children never formally happened, though the enrolment as of September 30, 1972 showed a girl in Grade 1 and a boy in Grade 3, along with 87 more students ranging from Grade 4 to 11. By the end of City School’s second year, the VSB was advertising that “About 25 places will be available this September for Vancouver students usually in Grades 4 to 12 to enroll at City School.”[7]

This advertising was referenced in a brief from City School parents to the Board of School Trustees in June 1973, in which they outlined the scant planning, support and resources with which the staff were expected to provide an alternative to the mainstream. They described the “considerable limitations” placed on City School’s proper functioning:

- The school was set up on an inadequate “shoe-string” budget as an “experiment.”

- The Board authorities assigned four teachers to the school and with little pre-planning or organizational direction handed over the responsibility of developing the program and running the school with no assistance from special staffs within the School Board.

- Parents were assured that a complete curriculum of instruction would be available to students which would meet existing secondary educational grade standards whereas there were no facilities for French or Science.

- The community resource program, a major aspect of the planned curriculum, was limited by the complete lack of properly insured transportation facilities.

- The four teachers, occasional aides, and an assistant who had to perform many other duties, such as secretarial work, have been expected to organize the courses, conduct individual tutorials, arrange and conduct group projects, arrange the community facilities, organize and supervise out of town trips, and carry out their responsibilities related to the teacher-pupil sponsorship procedure, a vital aspect of the program. In addition, they have been expected to cover a curriculum ranging from grades five to eleven. This range has now been extended to four through twelve.

- Numerous representations have been made to Board officials to effect needed improvements both to the organization of the school and the physical facilities. So far it appears that some improvements have been initiated to the physical facilities, most notable has been the provision of five years’ supply of toilet tissue and some eighteen toilet bowls. Some concessions have been made regarding an increase in teaching staff but, due to an expected increase in student enrollment no effective improvement in teacher-pupil ratio is expected.

It is our finding that, in the face of a serious need for an alternative education facility, the Board have set up City School as a gesture only, and presently regard it as a nuisance factor.[8]

The parents acknowledged that the teachers had “been successful in providing the students with the kind of human and considerate environment which is nurturing their learning development” but were concerned about the impact of the excessive work load on the functioning of the school, and the unwillingness of the Board to improve matters:

What is happening in effect is that the Board authorities are reacting to the basic requests of very concerned parents with numbers games and politics at the expense of the students.

This program is a unique and potentially successful answer to the growing disaffection of many of our young people with existing educational conditions. We are determined that the basic and urgent needs of this school be considered objectively and not swamped by rules, regulations and allocations.[9]

So that the school could “have a chance of success based on its unique and vital contribution to society” the parents asked for funding for an expansion of the staff to include a full-time program organizer, a reduction of the student-teacher ratio to 16-1, a system of gaining teaching assistants in conjunction with universities and other agencies, adequate administrative help, and transportation facilities.

The brief ended with an offer of any and all help to ensure the needed improvements became a reality, and the comment that “Surely the large advertisement in recent editions of the Vancouver Sun and Province inviting applications for enrollment indicates that this is no longer an ‘experiment’ but the nucleus of a very significant aspect of our educational system.”

1972-1972

Not long after the parents vented their frustration at the VSB’s failure to adequately support its token alternative school, some publicist was feeding glowing reports to whoever wrote editorials in the Province. This remarkable analysis was published on September 6, 1973:

“The clamor for change in the B.C. school system suggests that education is some kind of immovable object resisting an irresistible force. Nothing could be further from the truth, as the school year opening this week testifies… The Vancouver school system is, by any comparison, among the most progressive in North America. It launched the City School two years ago as an experiment in which the student is encouraged to learn at his own pace rather than at the pace set by his peers in class. Its continued existence testifies to its early success.”

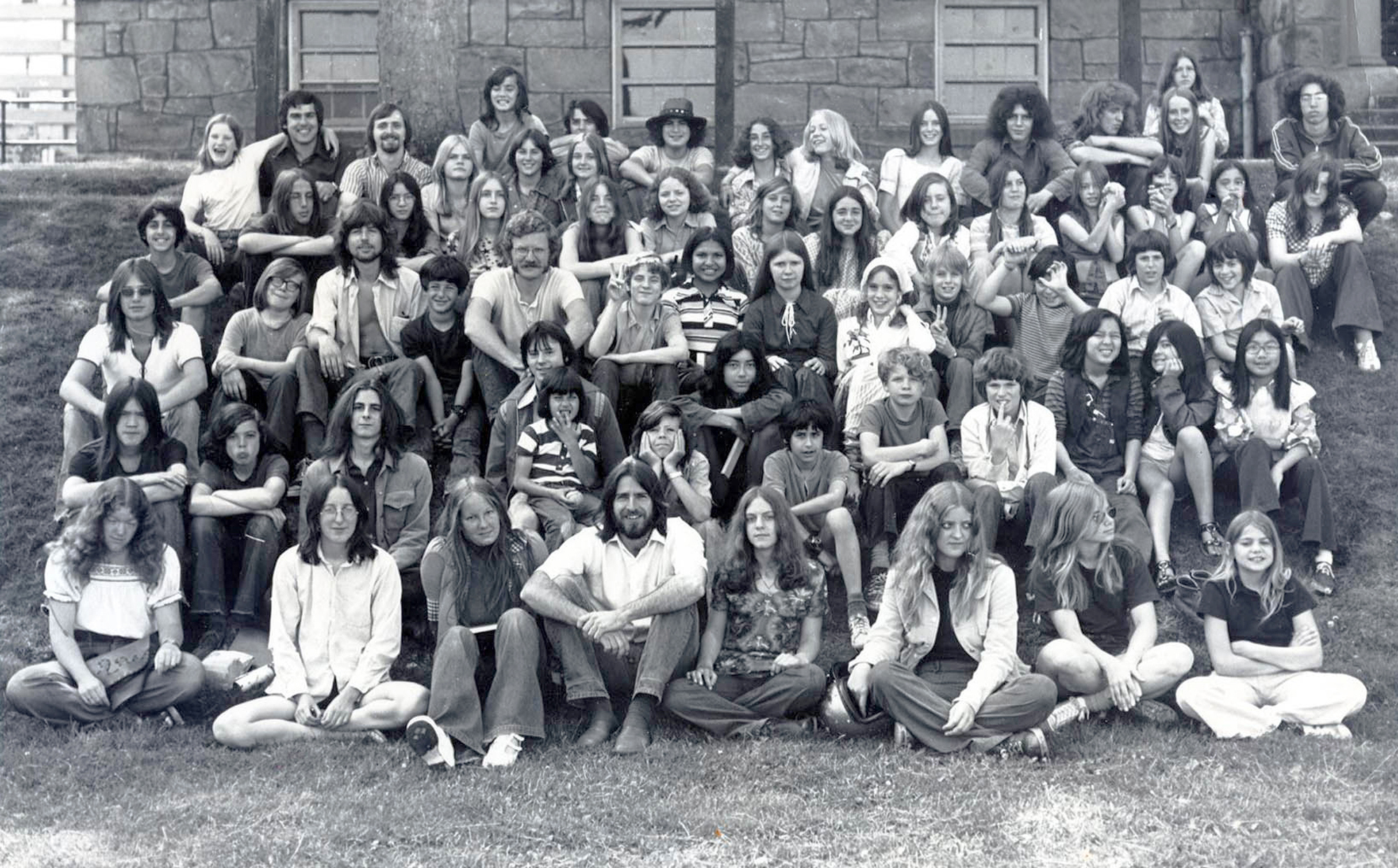

Of the four original teachers, Thom Hansen would remain until the middle of the 1976-77 school year, and Kit Fortune until June 1976. Staff assistant Fumiko Greenaway was part of the team from the beginning until June 1975. Sue Arundel, Joanne Broatch and Alan Crawford came in 1972-73 and stayed until June 1977.

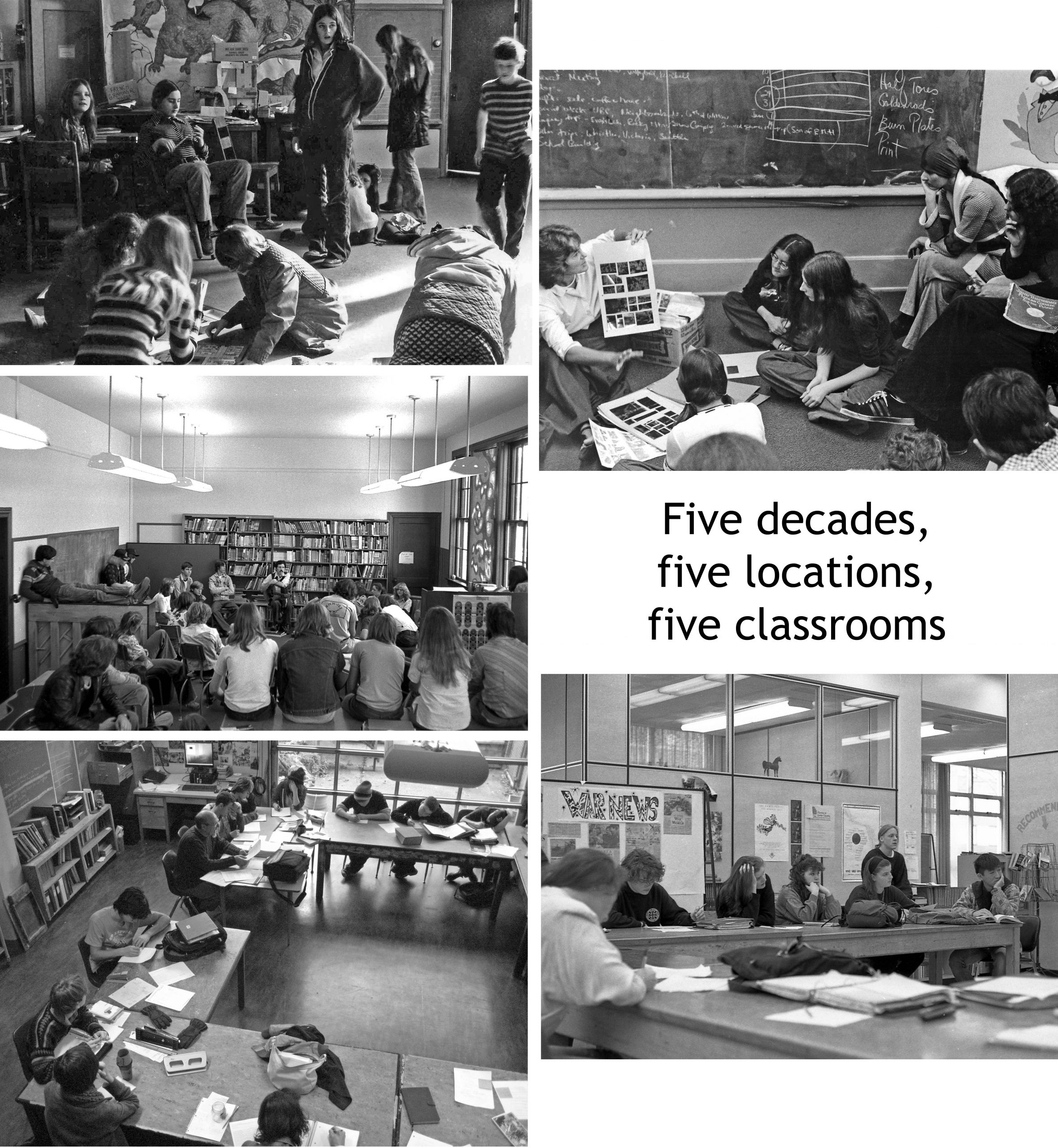

With a growing population (134 students were on the books that year) City School finished its third year in the portables at 10th and Ash but would pack up and move downtown in time for the 1974-75 school year.

Transitional brochure. Original logo design by John Greenaway.

Part II – September 1974 to December 1976

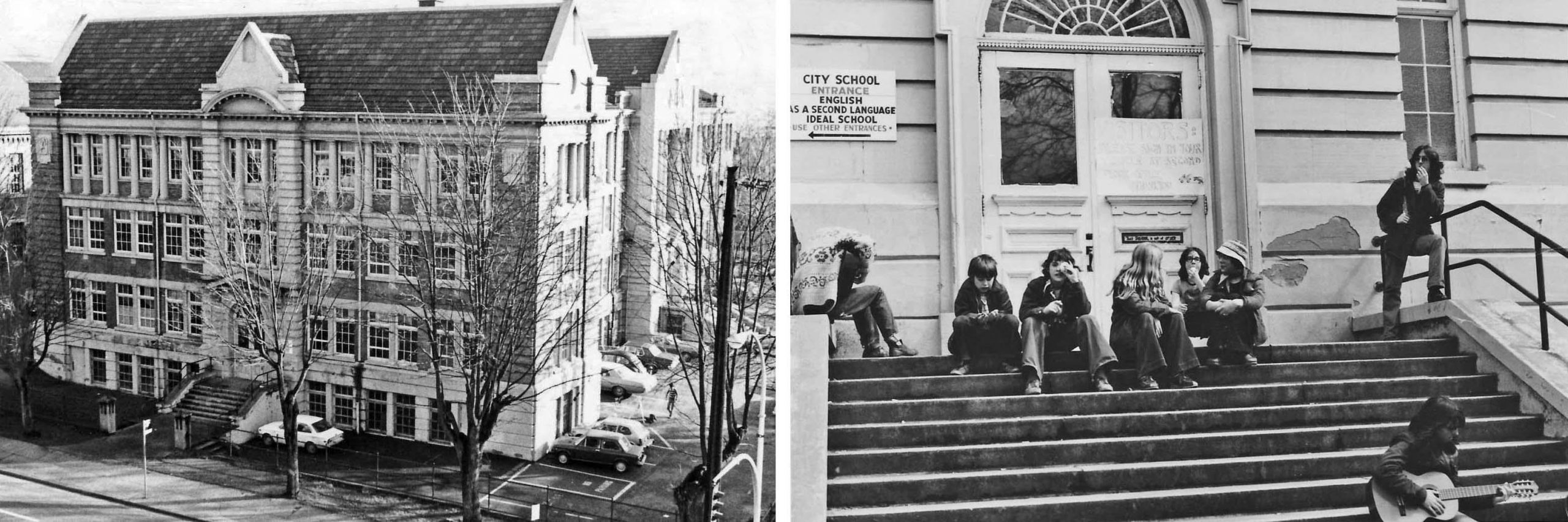

Sir William Dawson Elementary School at 901 Helmcken Street, built in 1914 and shuttered in 1972 thanks to declining enrolment, shared a piece of prime downtown real estate with the long-empty King George Secondary School building. Ideas floated for the site had included a commercial development of an office tower, an apartment and a personal care home, a conversion to a courthouse for family matters and a campus for Vancouver Community College. Its fate was in limbo when the VSB adopted the independent alternative Ideal School and needed a home for it and for City School. The two schools moved in for a September start in 1974. Trustee Betty-Anne Fenwick told the Vancouver Sun she expected that both schools would stay in the Dawson building for a year.[10]

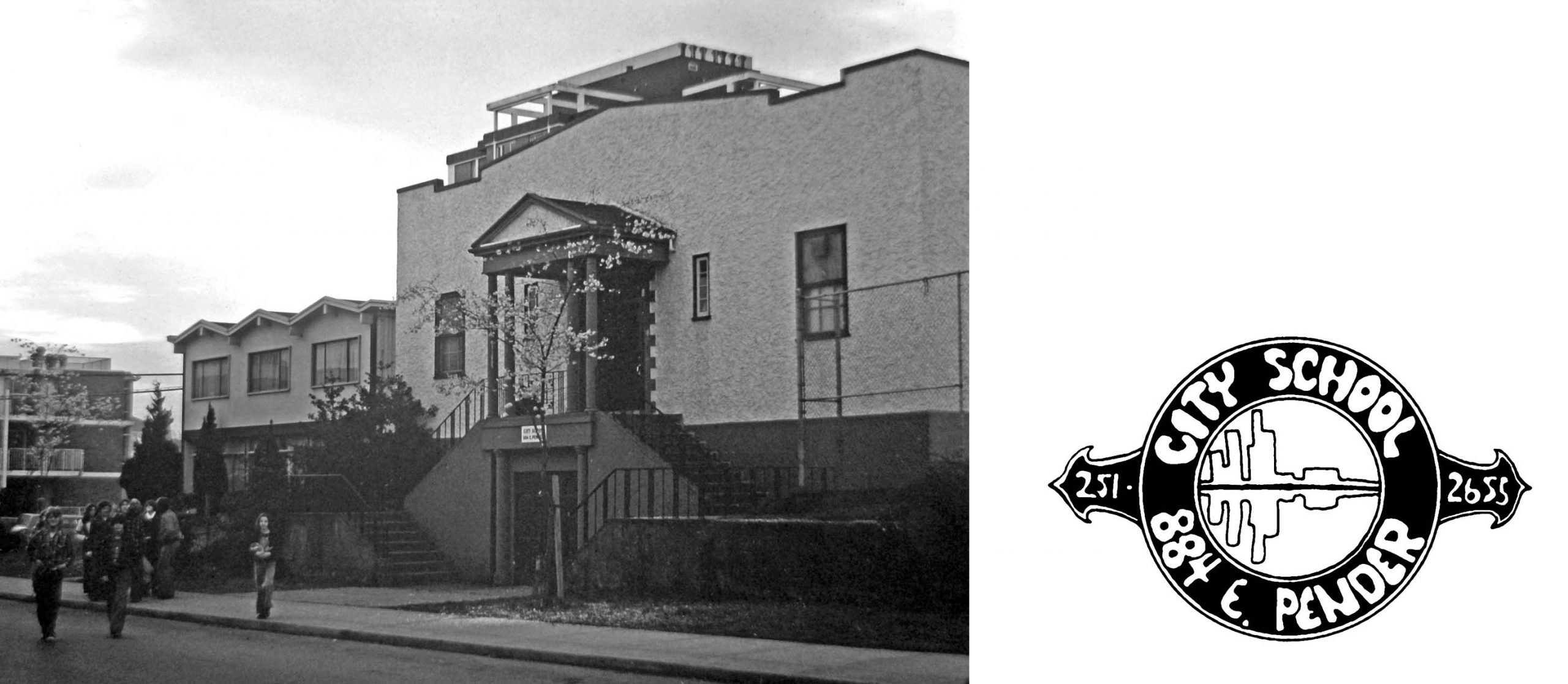

Sir William Dawson School at Burrard and Helmcken. The Helmcken Street entrance to our shared building.

The new location was a hit. Some news stories the previous spring made for greater awareness of alternatives which, along with word-of-mouth publicity and increasing referrals from mainstream schools, contributed to a population explosion. The nominal limit was 125 but, with turnover, some 176 students were on the roster the year of the move downtown. Barbara McClatchie and Daryl Sturdy joined the teaching staff.

City School made itself at home in a building that was, in the words of the visiting nurse, a “health hazard.”[11] It was decrepit, but comfortable. Vancouver Sun reporter Mary McAlpine visited the school in November and wrote,

“The blackboard reads ‘Science – Human Anatomy. This week featuring circulation and one bloody thing after another.’ Plaster has fallen off the ceiling. Paint has peeled crisp along the walls, lights are out, pipes exposed, sofas sag. But City School has a long waiting list.”[12] And what was City School doing that made it such a magnet? City School “breaks every apparent order of the old school system – absenteeism is ignored, desks don’t exist, teachers look scruffy and sit on the floor, students loll with their feet up, reading newspapers. What it doesn’t ignore, and claims to teach better than School Proper, is learning.”[13]

A brochure explained the school’s philosophy:

We feel that, functioning ideally, a school will:

- allow education to follow a natural life pattern in order to be most memorable and effective;

- promote a feeling of self-worth in an individual;

- create a situation where people are concerned with each other and their community to help break down the impersonality of our society;

- help the people in the school to communicate their feelings and ideas, to find more and better ways of expressing them, and to listen and respond openly to others;

- give a person a chance to make decisions which affect him to develop self-responsibility and independence;

- include experiences from many areas – art, music, literature, philosophy, science – and the chance for an individual to discuss them and to relate them to himself;

- include opportunities to meet the community and learn to deal with it.

Most important, the school should provide the atmosphere where the learning experience is one of mutual trust and sharing; it should be a learning community.

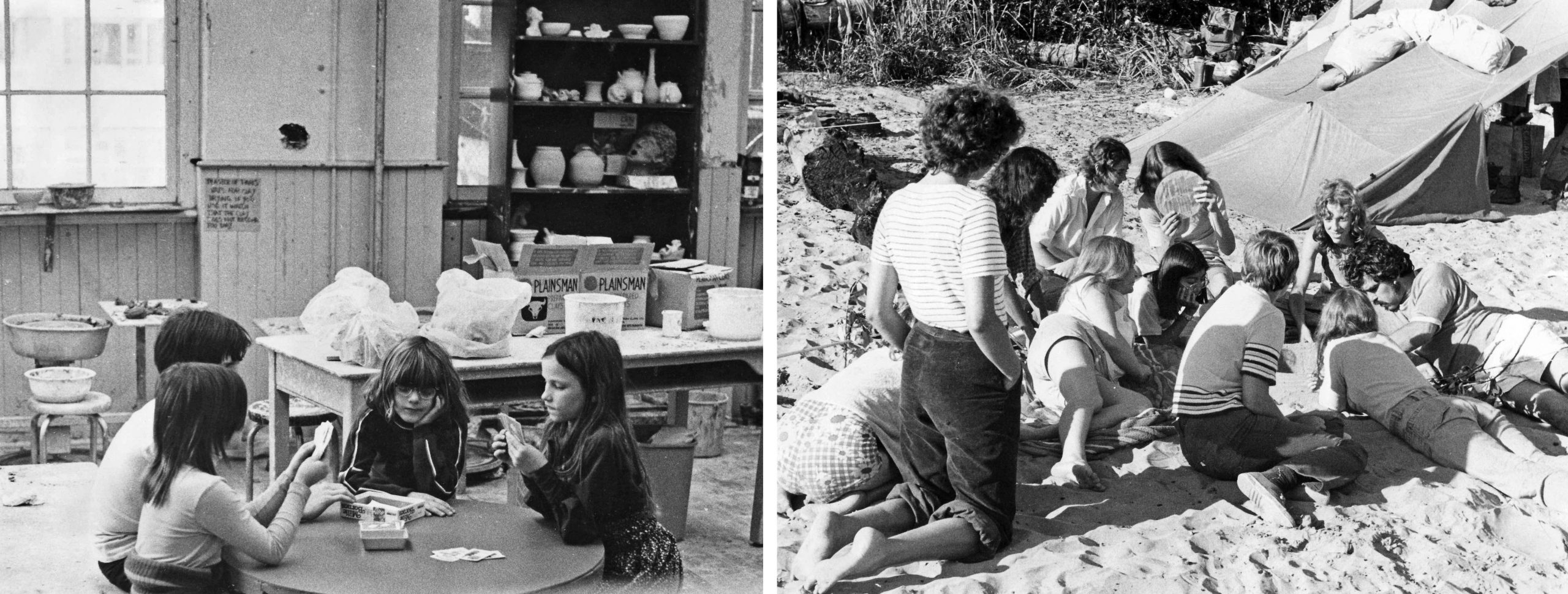

A learning community. Beginning of the year camping trip.

The brochure described the admission process:

Admission to City School is by application. There is no screening. Students who apply are placed on a waiting list by date of application. Approximately every two months, vacancies are filled chronologically from the waiting list. Prospective students visit the school for a few days, then decide with their parents whether they wish to attend the school.

Students were responsible for making a sponsorship agreement with the teacher of their choice, with whom they met regularly to discuss and assess their progress. The sponsorship agreement was critical. Either the student or the sponsor could cancel the agreement at any time, but a student could not remain enrolled without a sponsor after a week’s grace period.

The brochure outlined what students were expected to do:

- attend regularly (or be accountable if they were involved in activities off-campus)

- inform themselves about requirements for post-secondary studies and fulfill them if that was their plan

- involve themselves in the democratic decision-making by which the school operated

- know what courses and activities were being offered

- “select their program of studies and their method of acquiring the basic skills and be responsible for those decisions”[14]

- have an awareness of what other people were doing and be considerate of them

- keep themselves supplied with whatever materials they needed in their education and take proper care of the equipment and physical facilities of the school.

The education program was described as including work experiences, mini-courses and field trips using the resources of the city extensively. Evaluation and accreditation would occur as students desired, in consultation with their sponsors.

A final section of the brochure let parents know what they were in for:

Parents are expected to be involved in both the philosophical direction and the day-to-day operation of City School. They are encouraged to offer themselves as resource people in the school and to take part in any school activities in which they have an interest.

Decisions involving the philosophy of the school are made by teachers, students and parents collectively. New members of the staff are selected by the present staff in consultation with students and parents. The day to day administration of the school is accomplished through weekly staff meetings in which decisions are made democratically. Students are encouraged to attend all staff meetings.[15]

Many parents were very involved, especially when conflicts arose between the City School community and directives from the VSB administration. This would happen repeatedly over the years and the first major test was at the end of City School’s second year in the Dawson building.

Until then, however, the school enjoyed a brief golden era of activities and endeavours. With six teachers and a large contingent of receptive students in Grades 4 to 12, City School operated more or less as it was designed to. Much of the school day was spent out of the building, but Monday morning’s General Meeting was the one thing to not miss. It was the forum for communicating what was happening for the week and for the airing of issues. Anyone could put items on the agenda and the time allotted was open-ended. Motions passed at General Meetings directed the school’s activities and how the community would function. Policies were created for everything from keeping the kitchen clean to where smoking was allowed. Plans were made for mini-courses, seminars, speakers, fundraising, science-oriented road trips, arts fairs, music nights and all-school camping trips.

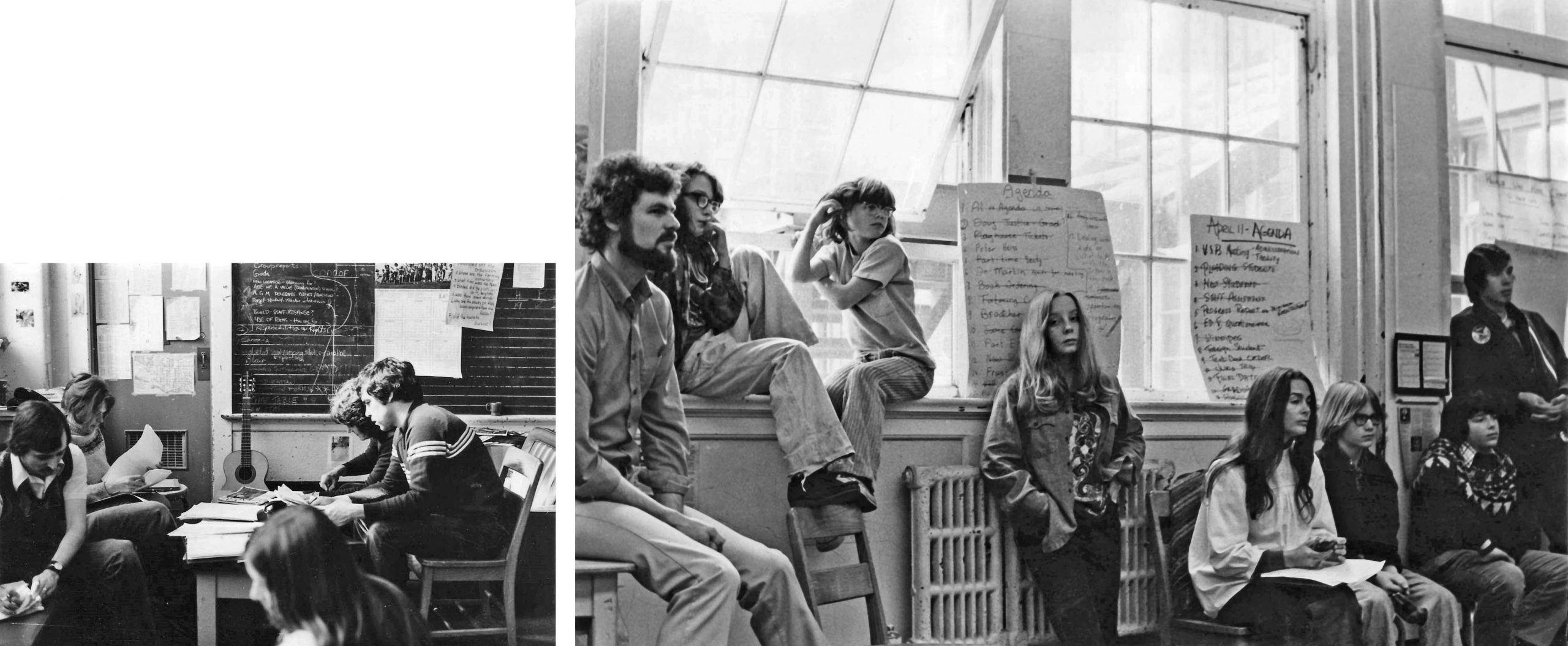

Friday staff meeting. General meetings could sometimes be a test of endurance.

New students received a document describing the whats, whys and hows of being a City School student. The primary obligations were to have a sponsor, to master (or improve in a measurable way) basic skills of communication, computation and processing, to record and evaluate learning and to be involved in the operation of the school.

In a section named for James Herndon’s How to Survive in Your Native Land, a lengthy list of suggestions was presented under headings roughly correlating to regular school subjects.

The headings and some ideas:

- Encounter people and ways of life different from your own

- Live with another family.

- Visit residential sub-societies (homes for the elderly, etc.) Sample different ways of making a living

- Be an apprentice for a day.

- Talk to some people who are self-employed. Find out the pros and cons of their position.

- Gain an awareness of the mechanics of society

- Attend City Council meetings for two or three days in a row. Report on the happenings.

- Investigate an organization that serves the needs of a minority group, e.g. Gay Liberation, Vancouver Status of Women.

- Involve yourself in some regular activity which will help you learn to keep your body fit

- Spend a number of sessions doing yoga, tai chi, kung fu, etc.

- Establish a school or community sports group, e.g. cycling club, softball team which would meet regularly.

- Explore ways in which to share subjective ideas with others

- Read and discuss an author.

- Learn a new craft or art.

- Experience the satisfaction of learning beyond the superficial

- Do a history of an ethnic community.

- Present an in-depth research project on a topic of your choice.

- Prepare yourself for living away from your parents

- Learn basic cooking. Learn about nutrition.

- Find out how to arrange a bank loan, a credit union loan.

- [Learn] about the natural systems of the earth and the universe

- Learn what the organs of your body do.

- Identify groups of plants native to specific biotic areas.[16]

Students were empowered to make meaningful change. They attended Friday staff meetings and on one occasion held a “Student Professional Day” to address the problem of poor attendance and lack of commitment on the part of some students.

In light of all this, it was no wonder then that the school community’s reaction was swift and strong when, in the spring of 1976, a vice principal assigned to City School began imposing rules.

The “edicts,” as they came to be known, conflicted with City School’s philosophy and undermined its autonomy. Instead of students writing self-evaluations with input from their sponsors, teachers would be required to write report cards. New students would be screened, and enrollment and the school’s finances would be handled by an outside administrator. Staff, parents and students would not be involved in hiring of new staff. In short, City School was to conform.

The ensuing uproar culminated in a meeting of City School’s parents, staff and students, with its liaison trustee and the principal of its administering school, King George Secondary, in attendance. The first item on the agenda was a review of the original concept of City School, which prescribed that decisions would be made collegially. A student stated, “The vice principal has no right to hand down edicts… unless he is far more involved with the school community where he will learn how we operate.”[17] Item two was “Where we are now.” The third item, “Review of vice principal position as promised by [VSB superintendent] Dr. Lupini,” generated a lengthy and confrontational question-and-answer session. The fourth item, whose ramifications would ultimately be more impactful than the vice principal dispute, was “Progress report on facilities.” The edicts handed down by the vice principal ended up being modified or ignored, but the facilities issue became an existential threat.

By 1976, a downtown city block used for nothing but City School and Ideal School was a treasure the VSB could no longer afford to keep: “School board trustee Pam Glass said the property is too expensive to tie up accommodating the schools.”[18]

The search for a suitable new building went on for months. Several sites were suggested by City School and rejected by the Board, which made the decision on September 14 to lease Sacred Heart School in Strathcona, and to move City School to 884 East Pender at the end of December. (Ideal School would be relocated to available classrooms at Lord Byng Secondary School, against strong objections.)

A committee of City School parents immediately petitioned the trustees to reverse their decision and allow the school to remain in the Dawson building until the end of the school year. Their brief explained that, of all the sites proposed, Sacred Heart was the only one unanimously rejected because of its distance from downtown, its physical set-up and lack of facilities. They had toured the building with VSB officials who had left them with the distinct impression that Sacred Heart was eliminated from further consideration, and that City School could occupy its current building for the following school year as the search for a suitable site continued.

City School’s pushback was not without consequences. In an interview with The Province when the decommissioning of the Dawson building was publicized, school trustee Pam Glass “announced that City School has caused the board ‘grave concerns’ about the academic quality of its program. For example, she said, ‘we are concerned about teachers with elementary qualifications teaching a Grade XI law class.’ Because of this concern, she said, the board has asked Superintendent Dante Lupini to have school administrators conduct a full evaluation of the City School program. ‘We feel there has been a shift in the philosophy of the City School since it started (about four years ago),’ she said. ‘For example, when the students and staff heard that a decision was in the offing to move to the Sacred Heart school, a notice appeared advising militant students to attend a board meeting and express their feelings.’”[19]

As moving day approached, City School appealed to the Minister of Education.

“The move has been violently opposed by students, parents and teachers who feel strongly they are victims of a school board that cannot and will not solve a problem relating to the continued existence of this special school which, in six years… has more than fulfilled the promise and hopes of its founders.”[20]

The City School community left its home for Christmas holidays in a less than merry mood. The building sat empty until long after the end of the school year; it was eventually razed and the land paved for a parking lot.

Abandoning 901 Helmcken to its fate. Waiting to start the march to our new premises in Strathcona.

Part III – January 1977 to June 1980

On the first school day in January, students and staff met at 901 Helmcken for the last time. Wearing black armbands and playing taps, they undertook a protest walk to the new site at Pender Street and Campbell Avenue, three and a half kilometres away from their former central location.

Sacred Heart School at Pender and Campbell. Updated logo.

Reporter Karenn Krangle caught up with them there later that week. She was told that the “100 students are finding Sacred Heart’s six small rooms too cramped, and the school has started a grievance procedure through the B.C. Teachers Federation to gain more space.”[21]

The layout was not conducive to the easy communication and many activities that the Dawson school had accommodated. The classrooms opened onto a corridor that ran the length of the building; none was large enough to comfortably hold everyone for General Meetings. A small room was fitted up as an office and a storage closet became the darkroom; the washrooms were elementary-student sized.

The mid-year move and battle against it took its toll. The staff, students and parents did their best to adapt to the unsuitable building and remote location (a leased school bus was provided to ease the transportation problem) in a sometimes unfriendly neighbourhood. As the school year neared its close, all four of the teachers made known their plans to resign and many students were opting to leave as well.

“The teachers’ resignations, all for independent, personal reasons, left the board in a quandary: Is there enough interest to keep the school going and will the board be able to find suitable teacher replacements? At a meeting Thursday between five trustees, two teachers, a handful of students and the school-parent consultative committee, all sides agreed that the school should continue but with fewer students and only two teachers.”[22]

The “End of an Era” camping trip was the last big outing for students and staff who had spent years together in their unique learning community.

“End of an era” camping trip at Porpoise Bay Provincial Park.

It is a testament to the passion and commitment of the twenty-nine returning students and their parents that the City School philosophy and core values were preserved through the turnover in staff and the eventual addition of an equal number of new students. Former student Sal Robinson was hired as staff assistant, providing institutional knowledge. The new teachers, Starla Anderson and Tom Morton, both had some experience in alternative settings.

After a couple of months the community was pulling together to lobby the board for another teacher, and Robbie McLennan came on board. An overnight trip in the fall, an exchange with a school in Prince Edward Island, a trip to Ontario, a year-end camping trip and a junket to the Shakespeare Festival in Oregon all helped to build cooperative spirit. The student population grew by a third in the next year, when the new alliance of students, staff and parents was about to face off with the VSB, again. It proposed to move City School into space at King George Secondary School.

The negative experience of Ideal School at Lord Byng was in the minds of the committee of students, parents and staff who wrote to VSB officials pleading for reconsideration or at least for more time:

“It has been suggested that a portion of King George High School be utilized as the permanent site of City School commencing in September 1979. However, the present circumstance of City School is such that with the disruption caused by several moves and changes in staff in the past few years, the program is just now taking hold again. Therefore it is our request and desire that City School should be left at its present site for one more school year… This would then allow the staff to strengthen the present program in order to provide the greater benefit to the students and to properly prepare for a move to an appropriate permanent site separate and apart from an established secondary school, if one can be found, or failing that, to King George pending appropriate renovations, for the school year commencing in the fall of 1980.”[23]

In its brief to the VSB concerning cutbacks in the 1979 budget, the Committee of Progressive Electors reiterated the difficulties facing City School in the event of a move.

“Moving City School into King George Secondary School has the effect of absorbing a very effective alternative program into the mainstream of a secondary school. A move of this nature also has the potential to generate stiff opposition from parents and students, similar to the furor that resulted in the relocation of Ideal School. Moreover, this is the fourth move in eight years for this program, a situation that is bound to produce problems in establishing an effective program.”[24]

The appeal was successful and City School remained at Sacred Heart for another year. But the stress of the fight and conflicting philosophies led to more staff turnover. Two of the three teachers moved on and Thomas Harapnuick and Dianne Turner took their places in September 1979.

The student population had stabilized at around 75, many of whom lived on Vancouver’s east side and were leery of leaving their neighbourhood. In anticipation of fewer students, one teaching position would be cut in the move to the West End. The school’s bus, already downsized to a van, was cut too.

Packing up our van for the last time. Grad ceremony at Rathtrevor Provincial Park.

Part IV – September 1980 to June 1996

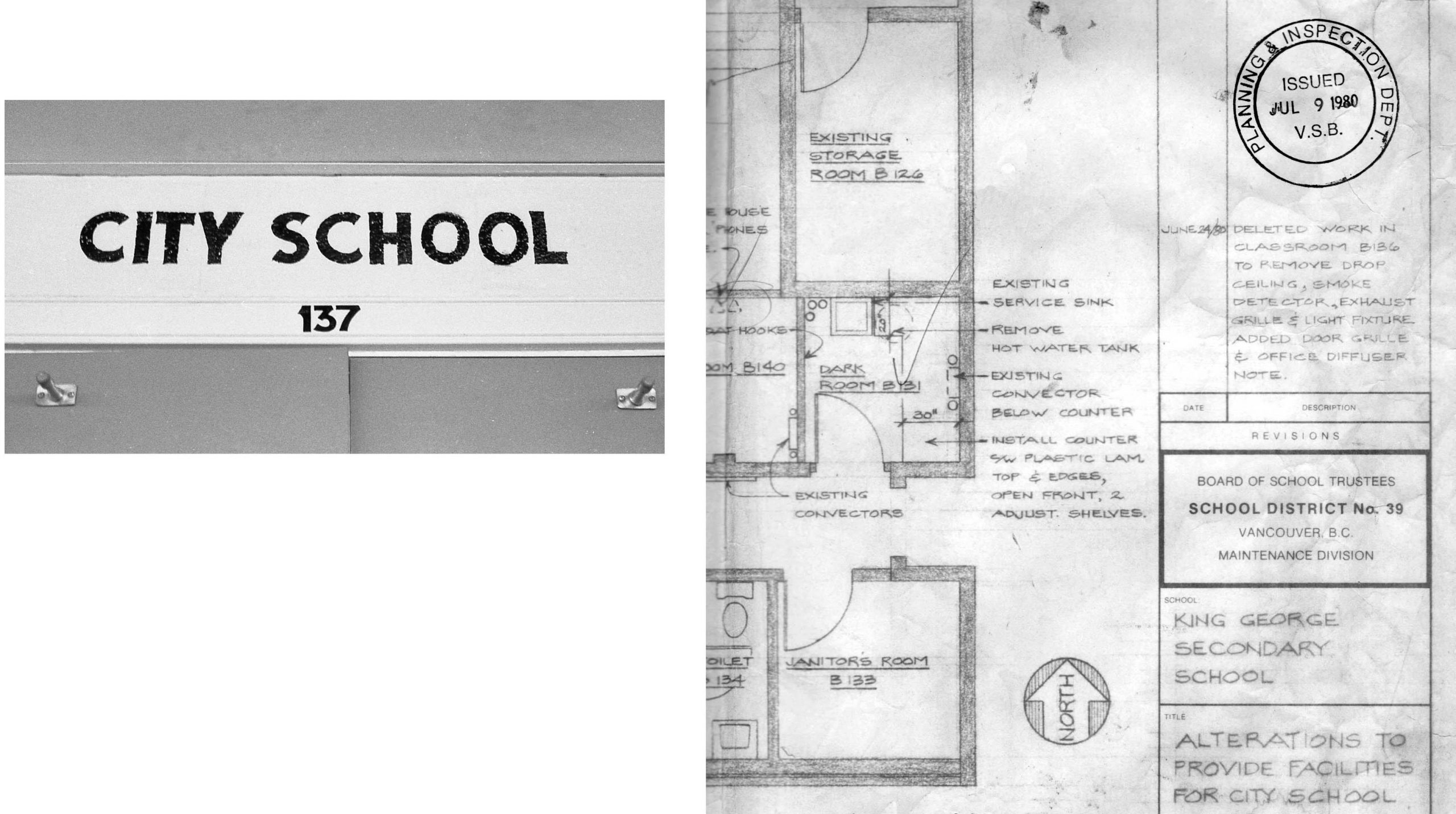

Our new “address.” Plans for the future.

Through the spring of 1980, City School’s Move Committee had worked with VSB officials to figure out how to optimize the space on offer at King George. The cafeteria, operating at a loss due as much to declining enrollment as to competition from fast food outlets in the West End, was modified to provide two large classroom spaces, an office, and a library and lounge area. The former teachers’ dining area became a seminar room and the former industrial kitchen functioned as a kitchen and art room; a janitorial closet became the darkroom. City School students uncomfortable interacting with people in main school hallways could use doors that opened directly to the outside. This would be home for fifteen years.

Only nineteen students from the Sacred Heart site remained with City School in its move to 1755 Barclay Street. Critical to the passing-down of City School’s philosophy and policies, eleven of those nineteen students and their families brought 33 years of experience, and the staff assistant a further five. The downtown location was a draw for West End and west side families. 53 students in Grades 8 to 12 were on the roster in the first year at King George and 63 the second. The elementary grades were dropped completely.

The settling-in process was more positive for the City School community – liking both the space and the West End neighbourhood – than for its “landlord.” There were many among King George students and staff who did not welcome the new inhabitants of their cafeteria. Despite that aspect of the move, City School would enjoy a few years of comparative calm and stability.

In May 1981, the VSB advertised City School, inviting applications from self-motivated students looking for “A comprehensive program which combines classroom learning with community studies; field trip experiences which enrich academic studies, including a variety of learning resources around the city; the opportunity to be involved in planning school activities; encouragement in developing goals; recognition of learning achieved through the pursuit of personal interests; a small, informal classroom environment.”[25]

The prominent position of the phrases “classroom learning” and “academic studies” in the advertisement’s description are indicative of a shift toward the priorities of the mainstream system, and away from the goals of City School’s founders. The teaching staff had a commitment to alternative education, but no experience in it; they read the old brochures and learned from ‘veteran’ students. (Even in the 1983-84 school year, some students and families were around who had been active in the 901 Helmcken days.)

A lengthy and positive news article indicated the creativity with which some curriculum goals were met. During a two-week mini course on consumerism, students compared prices at stores across the city. After one was thrown out of a drug store for asking what their dispensing fee was, reporter Nicole Parton became interested and visited the school.

“They suffered financial reverses and whooped when windfalls came their way. They searched for jobs, budgeted their paper earnings and moved into hypothetical apartments decked out with imaginary furnishings. Spending ‘city bucks’ rather than hard currency, their object was to get through a typical month with a reasonable portion of their incomes intact. They are the 40 students of Vancouver’s City School, recent graduates of a two-week consumer immersion course. While Victoria’s education ministry frets over its proposed consumer course, City School students simply plunged right in, calculating interest rates, studying banking fundamentals, insurance terminology, the rights and wrongs of credit, and even filling out their own income tax forms.”[26]

Consumer Week and Election Week were two of many theme weeks.

In one activity, students moved through a series of paper squares laid out on gymnasium floor. “This is life in a microcosm – a board game originated at City School, in which students roll dice to determine the number of squares they’ll advance in a typical month. They could land on a square commanding them to pay a veterinary bill, or a square directing them to the post office for a special letter that could be a bill, a birthday cheque from grandma…”[27]

The article inspired letters of congratulation from officials at both the district and ministry levels. The story was picked up by a magazine:

“If students see something happening in their community that they want to be a part of, they can suggest it as an area of study. If the idea fits into the curriculum, then teachers and students plan a course around it. This year alone, students have participated in over 100 field trips. City School students, in general, tend to be self-motivated and willing to try different approaches to learning.”[28]

In other words, still true to the school’s core values.

In September 1982, John Henderson replaced Dianne, forming a staff team that would see City School through troubled times and calm ones. John would stay for eleven years.

The 1983-84 school year was the last that City School offered a Grade 8 program. It was also the first in which students taking some Grade 12 courses would be compelled to write the provincial exams (scrapped in 1973 and resurrected ten years later) which were focused on specific content and would count for half the final mark. The spectre of a final exam put a damper of the creativity and flexibility with which course content could be treated.

The next existential threat came not only for City School, but for King George too, in December of 1984. Declining enrolment and provincial funding cutbacks were behind the VSB’s proposal to close King George and send its students to the four nearest high schools. The City School community joined with King George parents, staff and students in loud public opposition to any thought of closing the only high school on the downtown peninsula, particularly in light of the planned development on the north side of False Creek. A January meeting set the tone:

“At a noisy, rancorous meeting, about 400 people heard a school board budget team warn that King George secondary school may be closed if the city has to knock another $17 million from its education budget.”[29]

The VSB chair was accused of deliberately stirring up the community to make a point about insufficient funding for the district as a whole. One parent minced no words:

“If you still persist in your threat to close King George… and wreck the educational facilities of the West End, then we must accept, Dr. Weinstein, that you are using politics and the students as pawns in your political game.”[30]

King George had a reprieve: it would not close for the 1985-86 school year. (In fact, it would not close at all.) But its inhabitants spent many months on edge, waiting for bad news.

The 1987-88 school year was the sixth together for the City School staff. Thomas was in his ninth and final year and Sal in her eleventh. With a healthy student population and supportive parents, these years were City School’s longest period of stability. Until the early 1990s, energy was spent on learning and not on survival.

With only two teachers, one needed to have expertise in the sciences and the other in the humanities. Caroline Dixon took the latter role for nine years beginning in 1990-91. Jim Rutley became the math-science guy in September 1993. But City School teachers were always called upon to offer courses outside their specialties, and in doing so they modelled “life-long learning” every day.

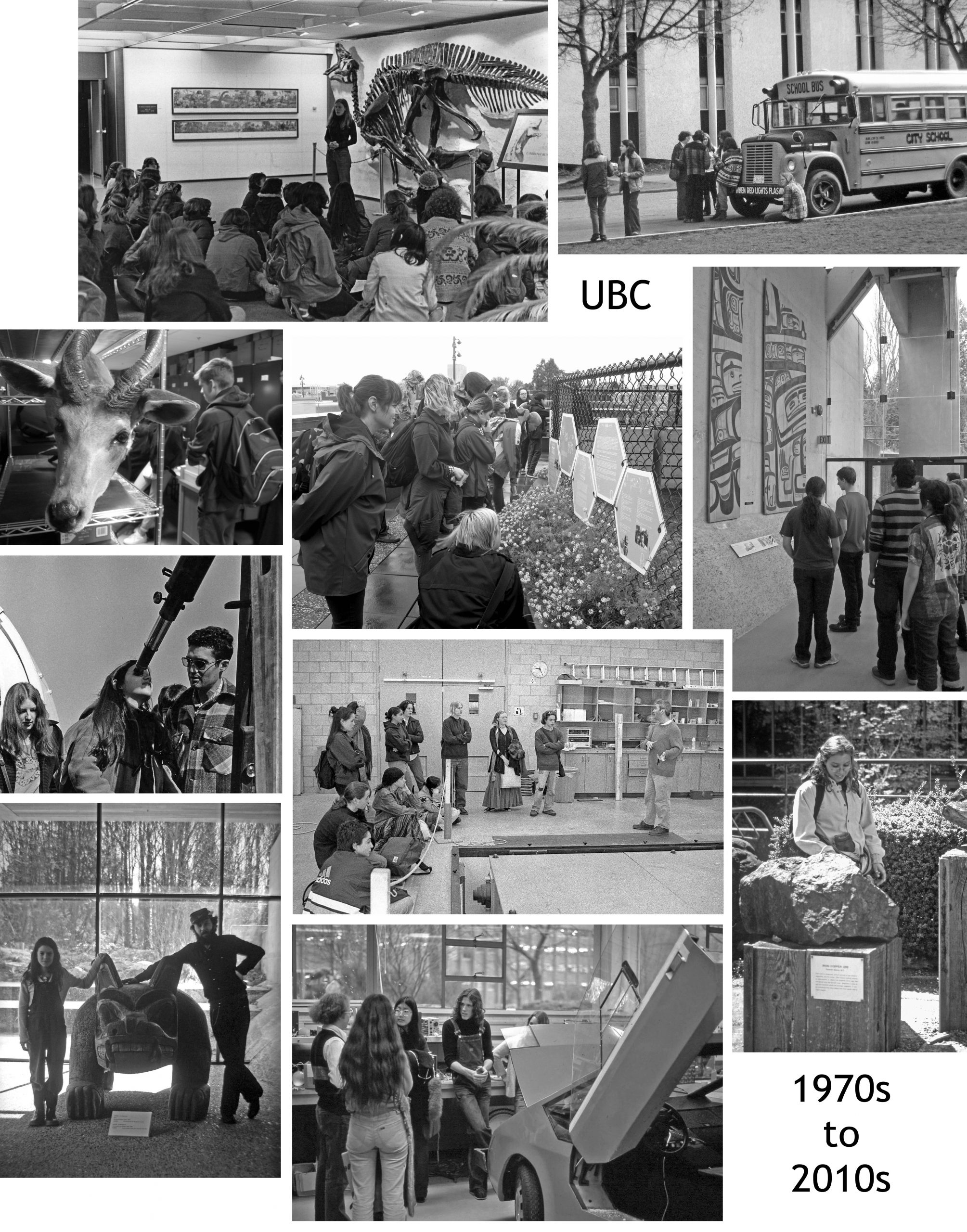

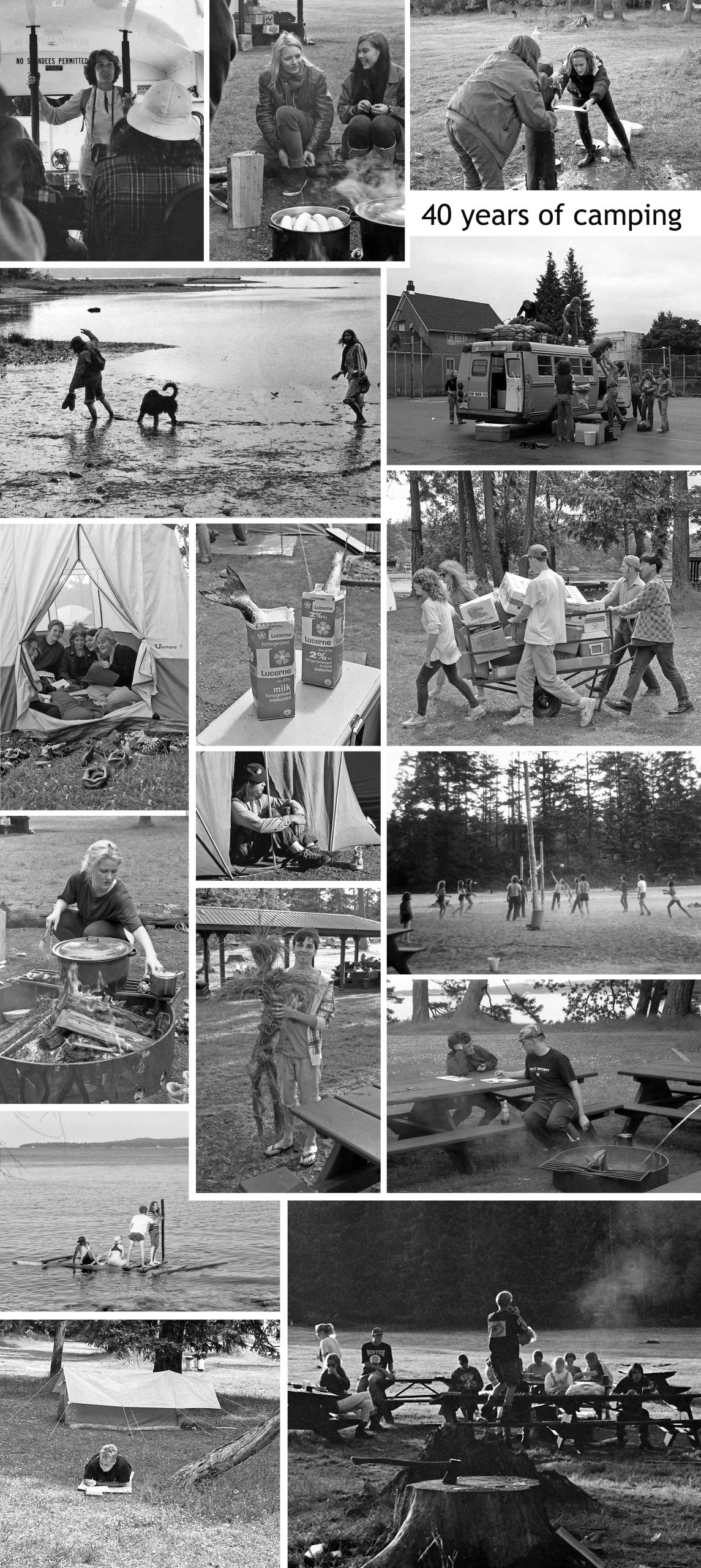

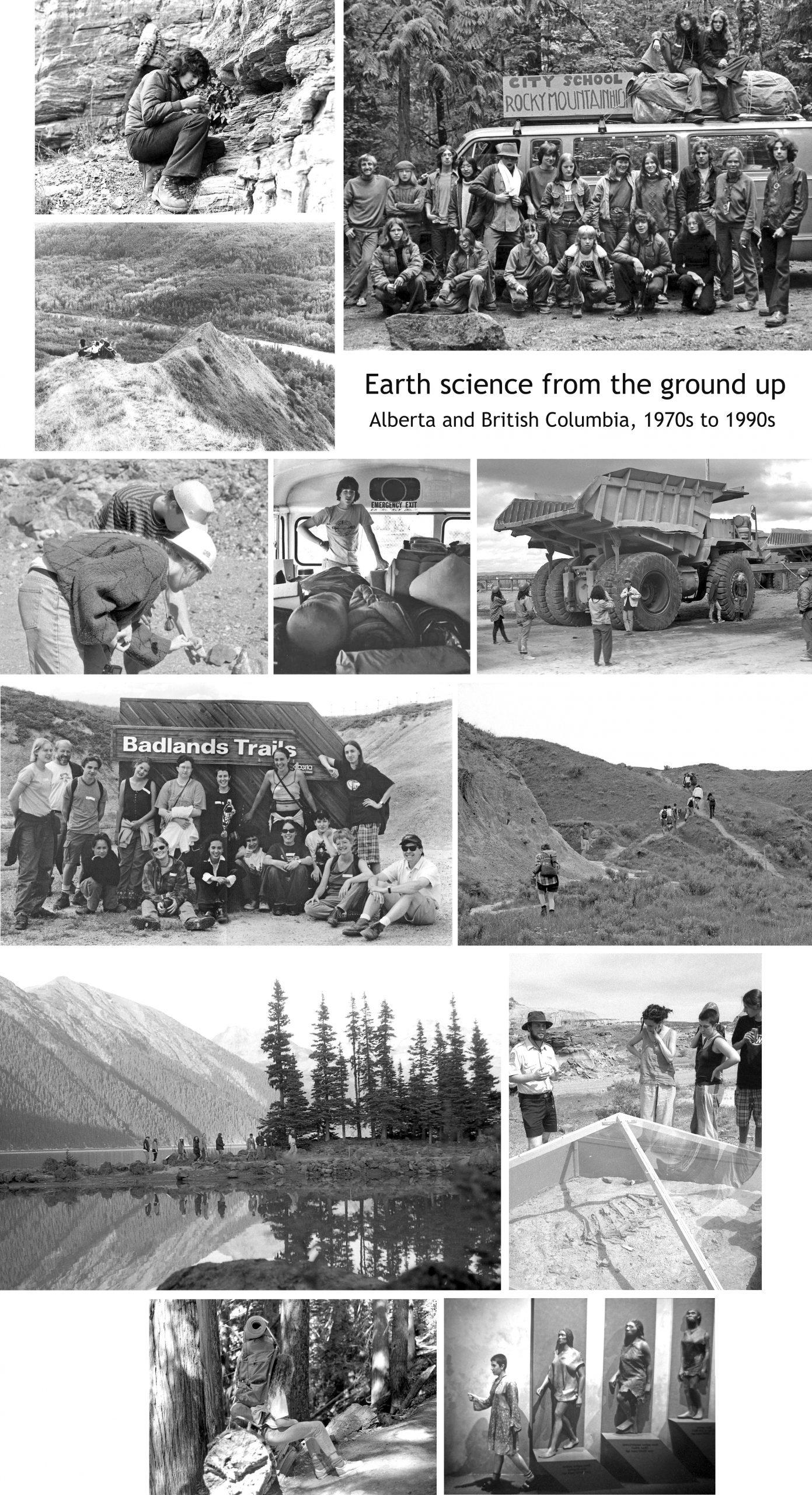

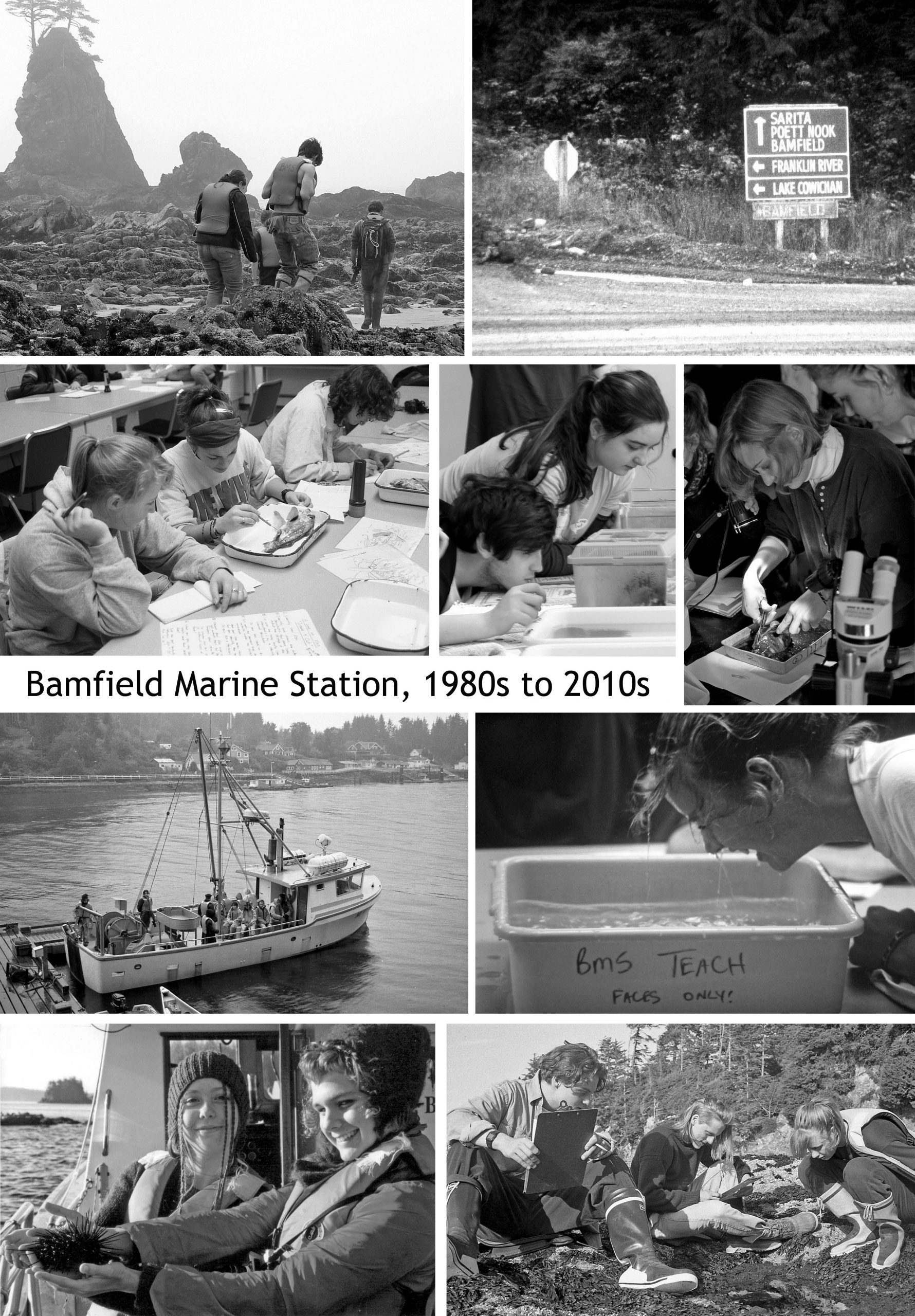

In addition to, and often instead of, classes in the building, City School continued to use learning opportunities in the city and beyond. Year-end camping trips were annual events; science courses were enriched by hikes in local mountains, biology trips to the Bamfield and geology outings to mines in the Rockies. General meetings were still the clearing-house for issues and planning.

On board the M.V. Alta in Barkley Sound. Making art in the kitchen/art room we were soon to lose.

On Friday, June 11, 1993, City School’s senior students were bracing themselves for their exams, and all of the community preparing to wish farewell to a long-time teacher who was moving on. Out of the blue came an order to clear everything out of the kitchen/art room, storage area and anteroom. Over the summer, that area was to be converted to use by King George for a lunch program. On Monday the students wrote a letter explaining the issue, proposing solutions, and calling a meeting of parents for Tuesday. The parents organized a protest which put a stop to the immediate plans.

Through the fall of 1993, meetings occurred in which City School’s concerns were made clear: loss of teaching space (the kitchen/art room as well as the main classroom, proposed as the eating area); nuisance of noise and smell; loss of space and security at lunchtime; a sense of helplessness in the face of invasion. The City School committee proposed several creative alternatives but, in the end, the “compromise” was that City School would lose its kitchen and art room but King George students would not eat their lunch in the main classroom.

When King George underwent accreditation in 1994-95, a weakness identified was the lack of a place for students to eat. In the fall, a VSB facilities committee inspected City School and the unused metalwork shop for their relative viability as lunchrooms. For the next year, City School had to operate with the constant distraction of its probable fate. Students, parents and staff met with administrators, planners and, once the decision to evict was made, architects. The new space would be half the size.

In May 1995, the VSB advertised for applicants to five district secondary alternative programs: City School, Ideal Mini School, International Baccalaureate Program, Montessori Pilot Program and Templeton Mini School.[31]

Reporter Gudrun Will surveyed enrichment programs in the district and her lengthy article featured the Churchill IB Program and City School, introducing it as “Vancouver’s oldest and least-known”[32] program.

Despite the promotion, City School’s population was dwindling. With a limit of 40 students, only 26 were enrolled in May of 1996 when reporter Susan Balcom visited and interviewed several senior students about how their school lives had transformed.

“For… students at a Vancouver alternative program called City School, the accomplishments [graduation and perfect attendance] are something of a miracle. Like many other teens who end up dropping out, for them, life in a traditional high school had become an ordeal. City School’s concept of a nurturing environment was a sharp contrast: students in small, multi-grade groups, lots of enrichment activities, and teachers who genuinely care.”[33]

On the issue of the low number of students, she spoke with the staff.

“Despite the program’s long history, [Sal] Robinson says she can’t help wondering if students from other secondary schools in the district even know they have an alternative. ‘I don’t think many people know about us. We’d certainly like to have more students and there are hundreds of kids on waiting lists for mini-schools.’”[34]

The 25th Reunion

City School celebrated its first quarter century in June 1996, and students, teachers and parents from every year back to 1971 came to the reunion. Two early students took the opportunity to produce a documentary, City School: 25 Years of Alternative Education. The reunion was a real eye-opener for the more recent students, and the sense of their school’s past that they gained was an unanticipated bonus.

Completion of the remodelling of the metalwork shop was promised for August of 1996, at which time City School’s belongings and furniture would be moved. With that assurance, staff planned to come in and pack after the end of June. What happened instead was that the first walls to come down in July were those that made up the City School office, the photos and artwork still on them. The staff worked in the plaster dust, wearing face masks, to pack up their school.

Part V – September 1996 to June 2014

In September, City School faced a grim situation. The new space was not ready, and the first meeting of the school year was held in the cafeteria in a circle of chairs tucked in next to a twenty-foot pile of furniture and cardboard boxes. There was no classroom, no office, no telephone. But there was a warning from the administration – not the first one – that if City School’s student population didn’t increase, staff cuts were likely.

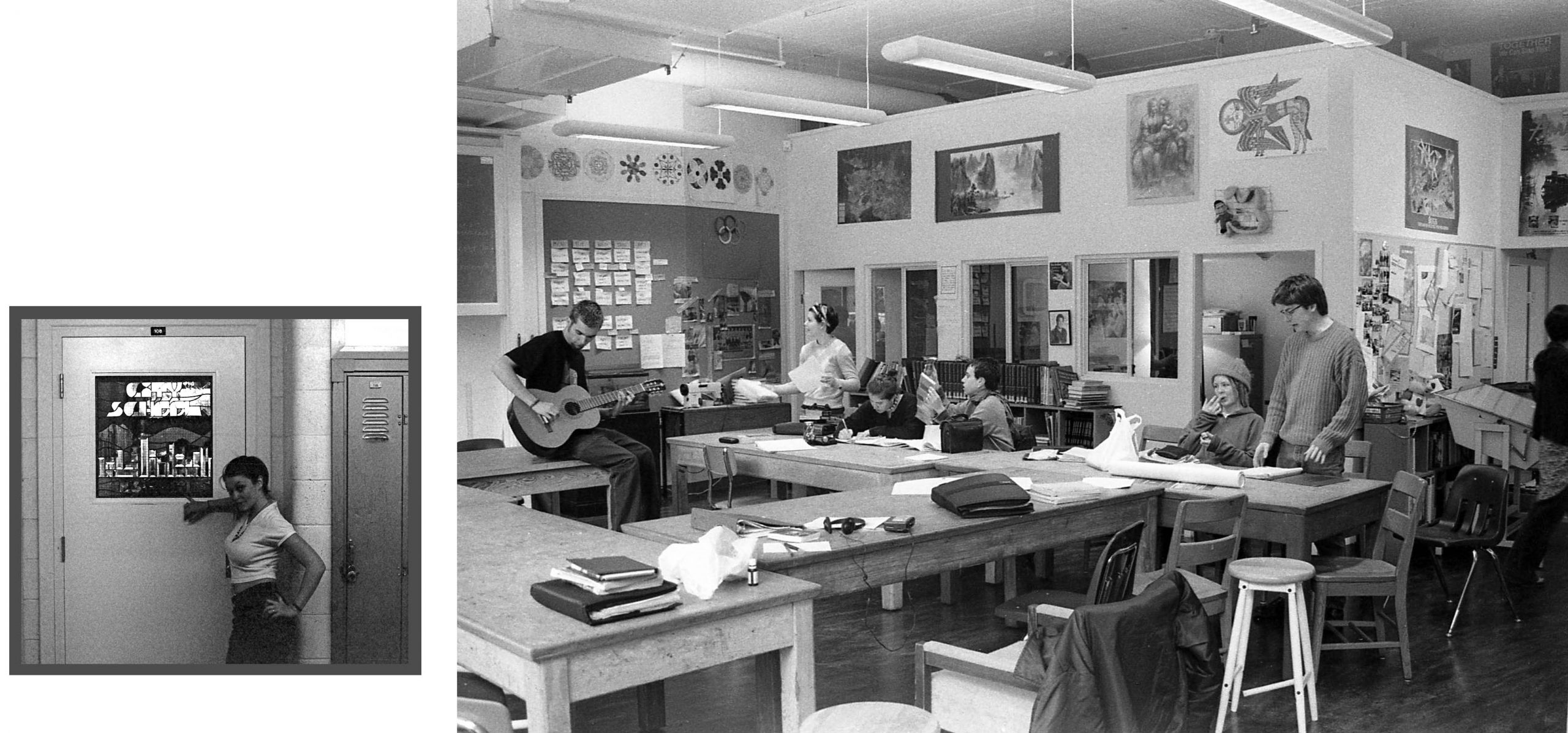

Room 108, now home. The repurposed metal shop was our new space.

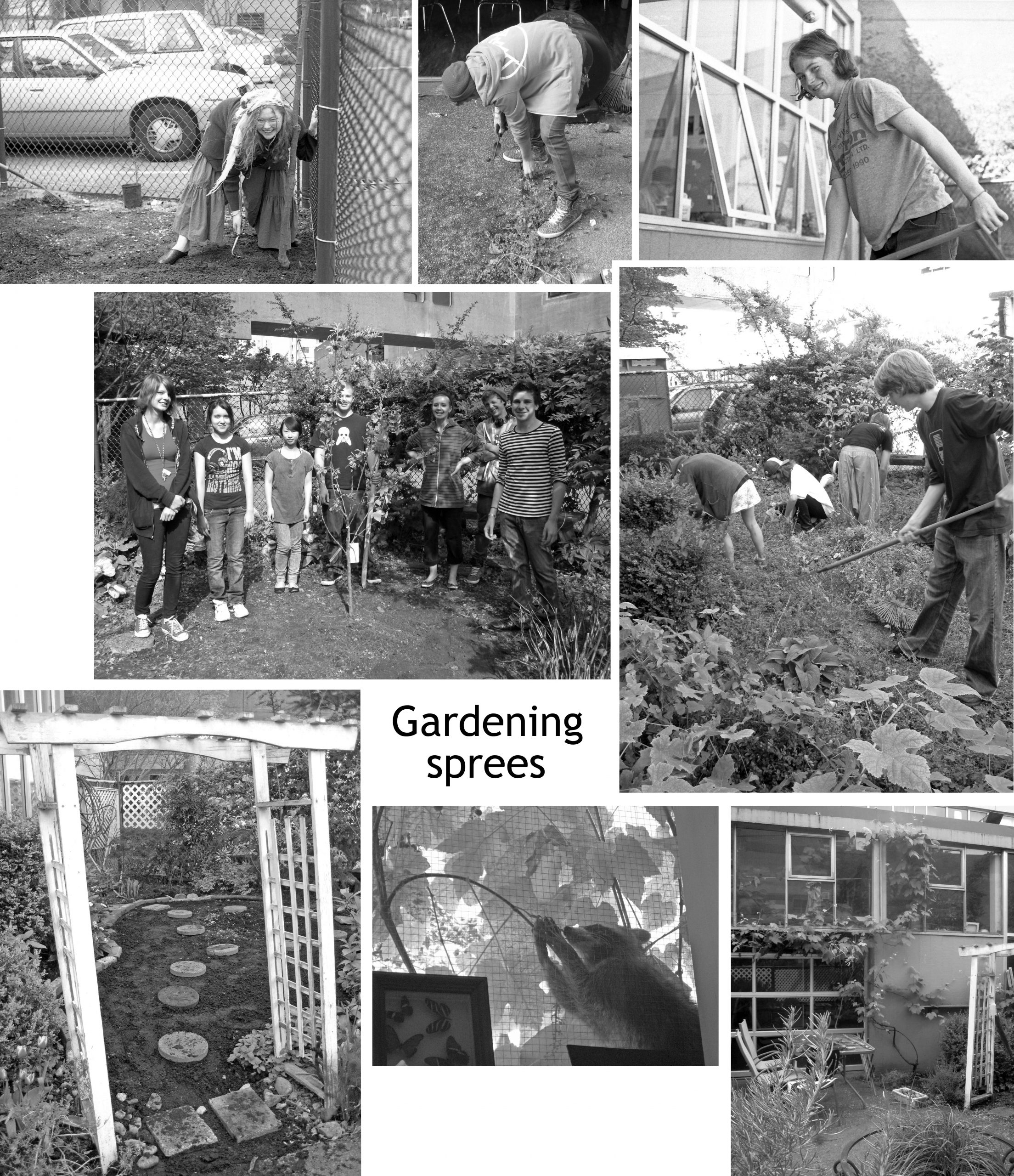

After a week, City School moved across the hall to its new location in the former metalwork shop. Some walls had been put up forming a small office and smaller computer room under a low-ceilinged loft reached by stairs with a stop at an eight-foot square mezzanine noted in the architect’s plan as “small classroom.” A kitchen area had been constructed, and glass replaced the metal in a garage door that opened onto a parking lot. City School retained its darkroom and seminar room (known as “Math Valley”), both reached through the cafeteria. The parking area and adjacent landscaped plot would later be fenced in to allow for a school garden.

This was the fourth year together for the staff and the third for many students and families. The community worked to make the new space home, and got on with school. The year culminated in a geology trip to Alberta’s Dinosaur Park, and the traditional all-school camping trip to Newcastle Island.

Around this time, the alternative education landscape in Vancouver was shifting. In only three years, the number of district alternative programs advertised by the VSB doubled to ten. (A similar number of alternative “rehabilitation programs” had been operating for years but were not advertised.)

The older programs had begun life simply as alternatives to mainstream. Over time, some, such as City School and Ideal School, had attracted students interested in academic post-secondary paths. They were funded solely by the VSB, and open to students living anywhere in Vancouver, not just in the catchment area of their administering school. Others, such as Total Education and 8J-9J, were funded by the VSB, with provincial ministries providing specialty staff to meet the non-academic needs of the students who attended them. (See Mary-Jo Campbell’s “The Rise of Alternative Education in the Vancouver School District“ for more on this topic.)

In his March 1998 Secondary District Program Review, retired VSB principal Bob Pearmain looked at all the programs. One of his recommendations was to clarify the differences in focus among them. This was a welcome change. Until the Pearmain report, all education options had been listed in the VSB’s Ready Reference with no indication of their aims or target clientele. This meant wasted hours of frustration for parents seeking appropriate alternatives and wasted hours of repeated explanations for the person answering the phone at each school.

Now, material would be published describing each program. “District Specified Alternative Programs” (DSAPs) would include French Immersion programs and others with a specialty (IB, arts, and so on), anything with “mini school” in the name, and City School. It was never a completely comfortable fit.

In City School’s first decades, there was no screening; any kid who wanted to give it a try was welcome. And many of those who came were having trouble in school for any number of reasons. When the Pearmain report split the alternative river into “academic” and “rehabilitative” streams, City School kept one foot in each, accepting any student with the academic prerequisites (i.e. passed Grade 8) who wanted out of mainstream.

As time passed, keeping the founding philosophy alive in daily life at school while meeting the accountability expectations of the people paying the bills was not within the skill set of the staff or even a desire of some students and parents. The notion that “teachers and students will plan together and the curriculum will be developed through emphasis on the learning process rather than the teaching act” (as per Dr. Clinton’s proposal) was lost in the mists of time.

This fundamental change in how courses were “delivered” (i.e. teacher-driven rather that student-led) stretched the limited staff resources. The focus of what courses they were able to offer had to narrow.

When university entrance was predicated on a certain selection of courses as well as provincial exam performance, choices were necessary. Algebra or Consumer Math? English Lit or Communications? The City School community opted for the more academic ones. If bright and gifted students were miserable in high school, where would they go if they didn’t want to drop out? City School was their refuge, if they only could find it.

VSB brochures didn’t help much in generating new students, and high schools were loath to see anyone transfer out because fewer students meant fewer teachers. A DSAP [see above] working group was struck to determine criteria for creating new programs when every secondary school wanted one of its own, but each must be distinct from the mainstream and from all the existing programs. The proliferation of alternatives may have had a hand in City School’s often tenuously low population; when programs were discontinued some years later, City School gained.

Budget cuts, layoffs and maternity leaves all contributed to the instability of the City School staff over the next decade. Jennifer Luis took on the science-math role for nine years, and Susan Gerofsky spent four years as the humanities teacher. With the support staff position cut by half in 2002, Grade 9 was dropped.

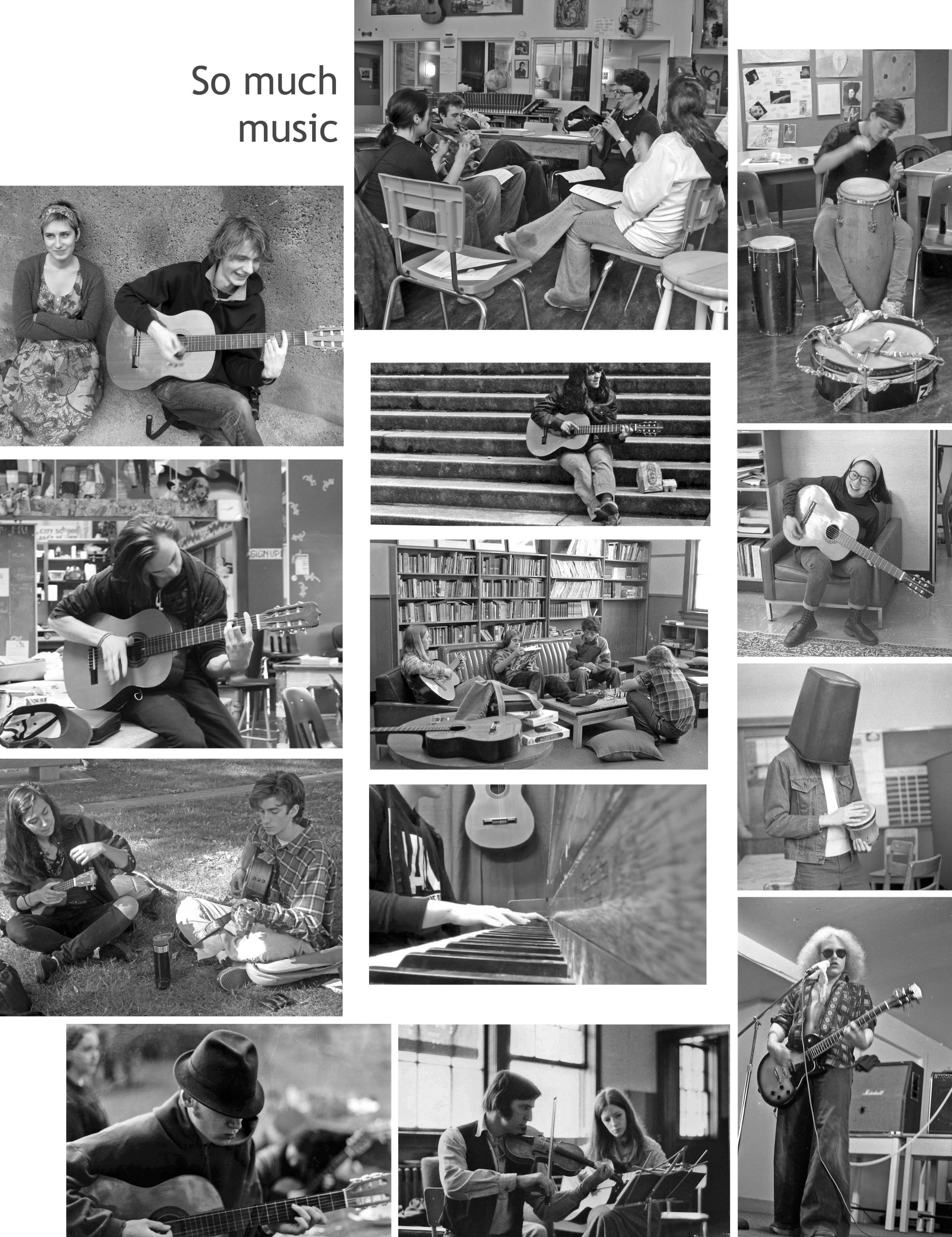

City School has never been short of musicians. Hunting for fossils in the Alberta Badlands.

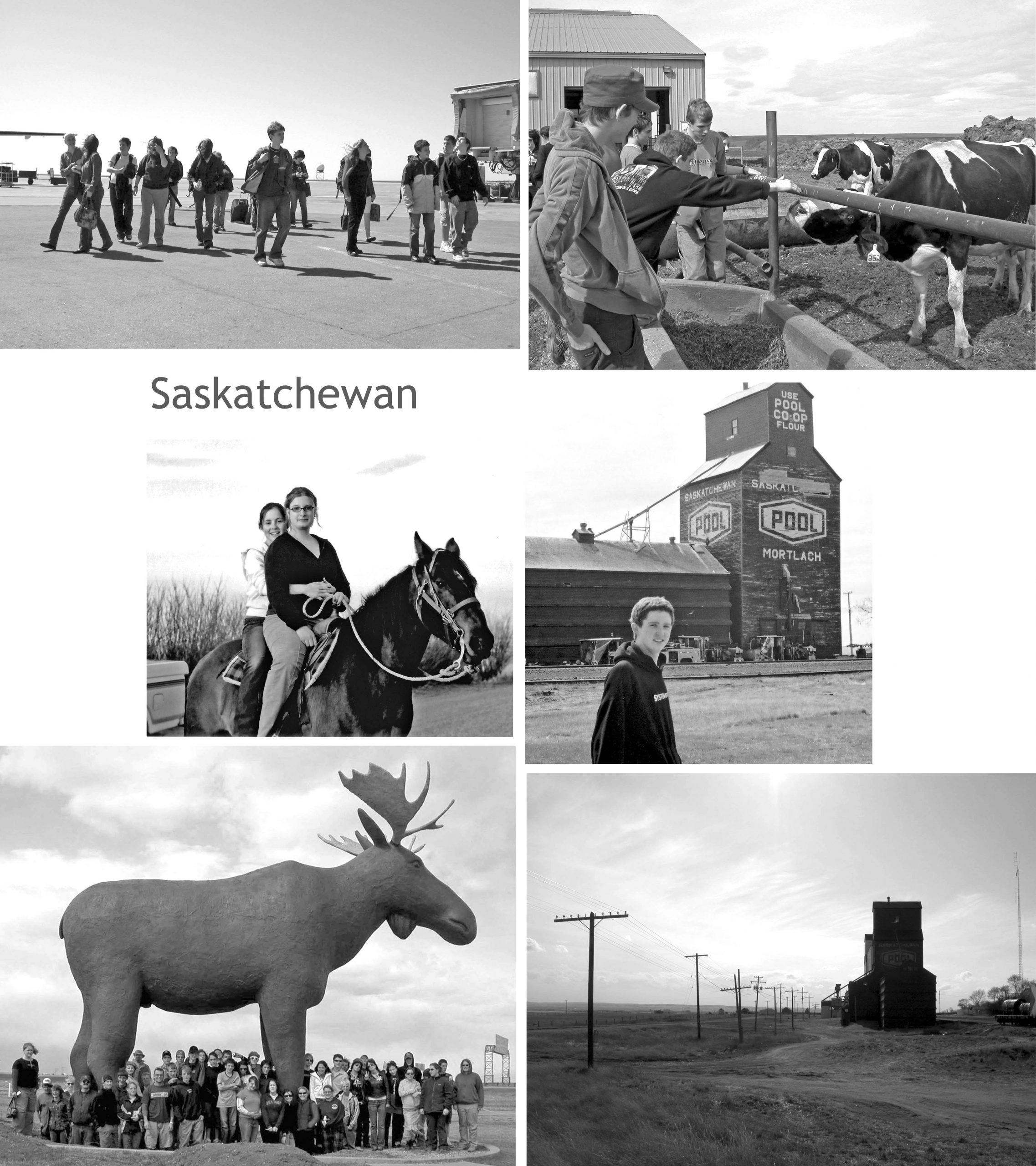

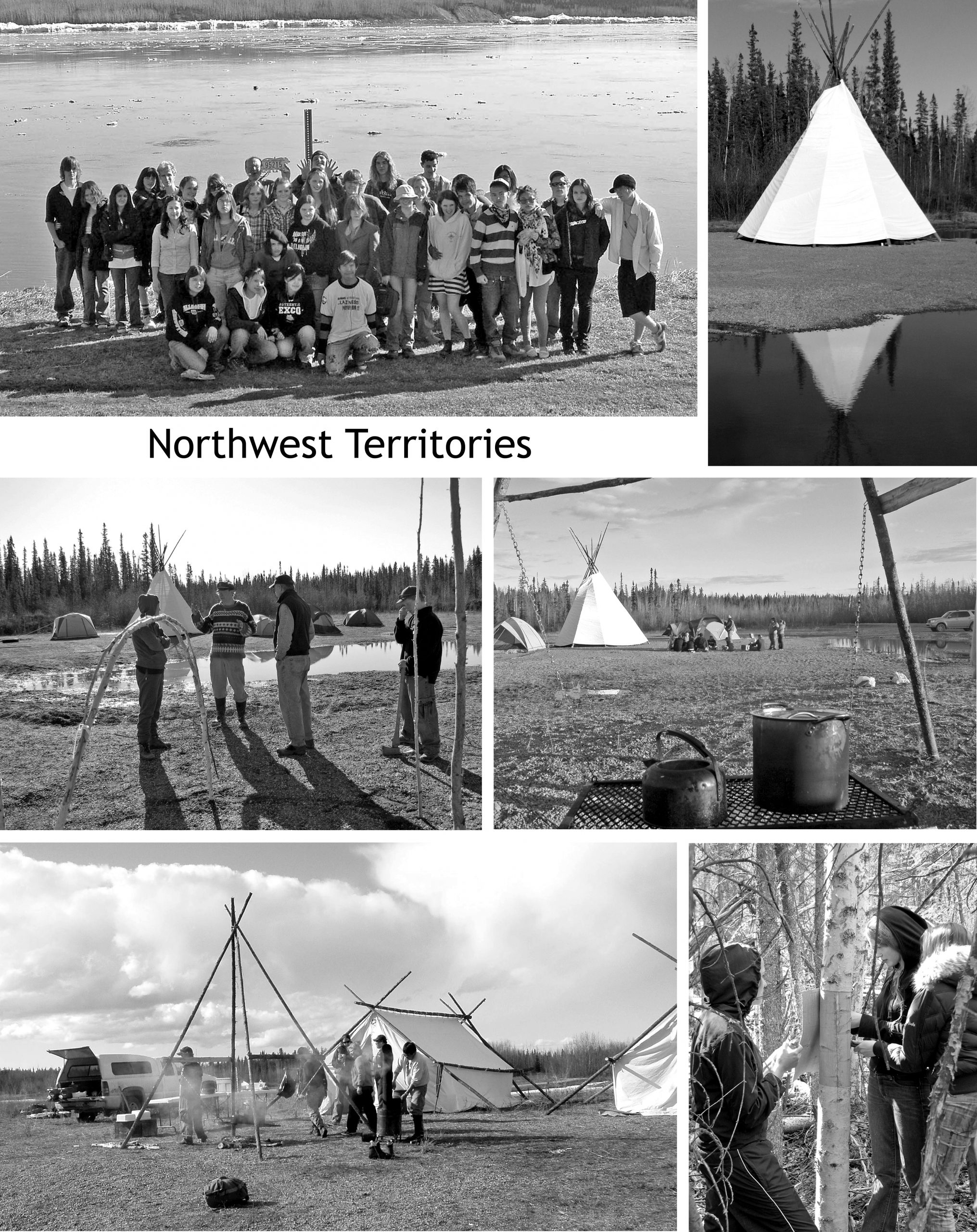

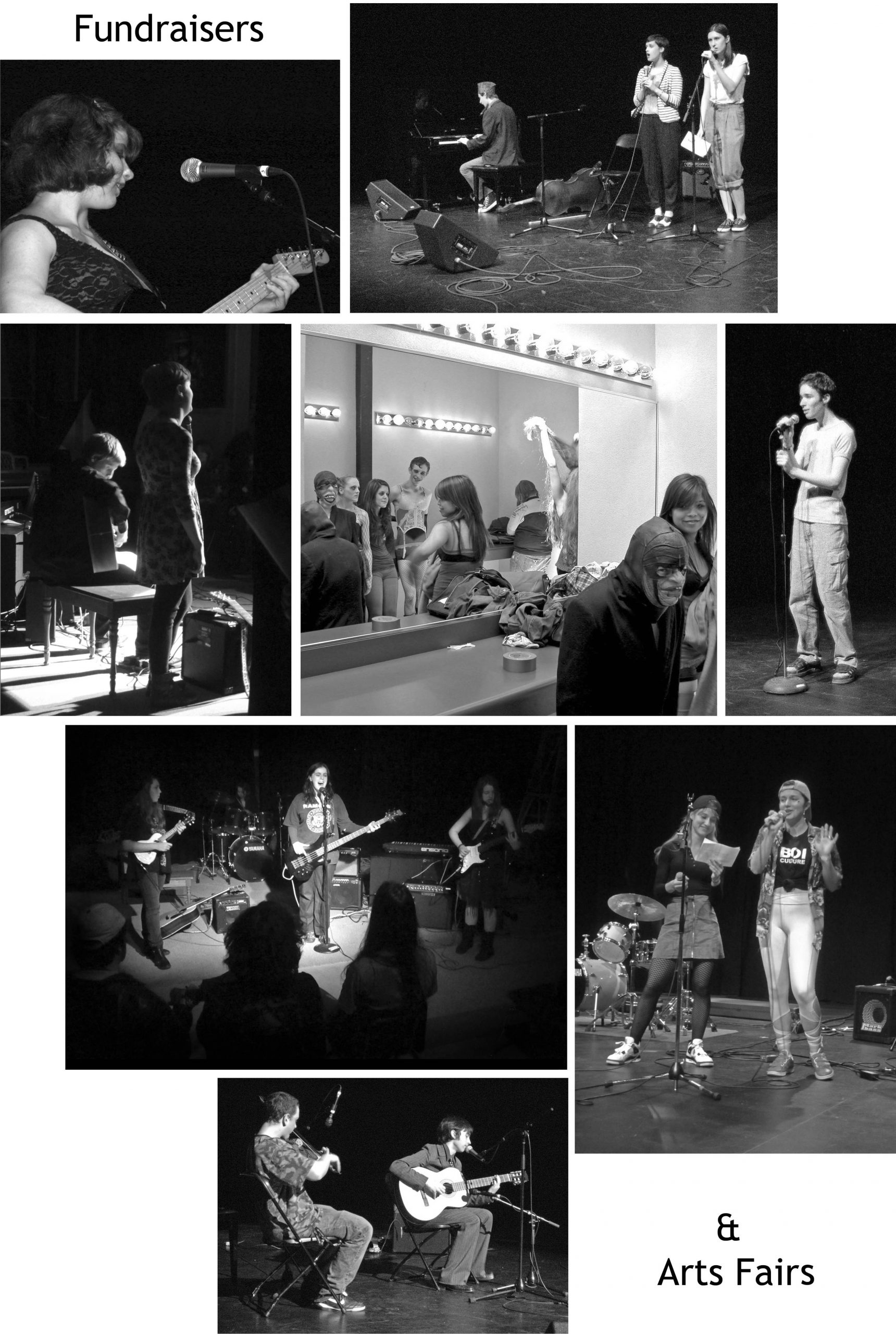

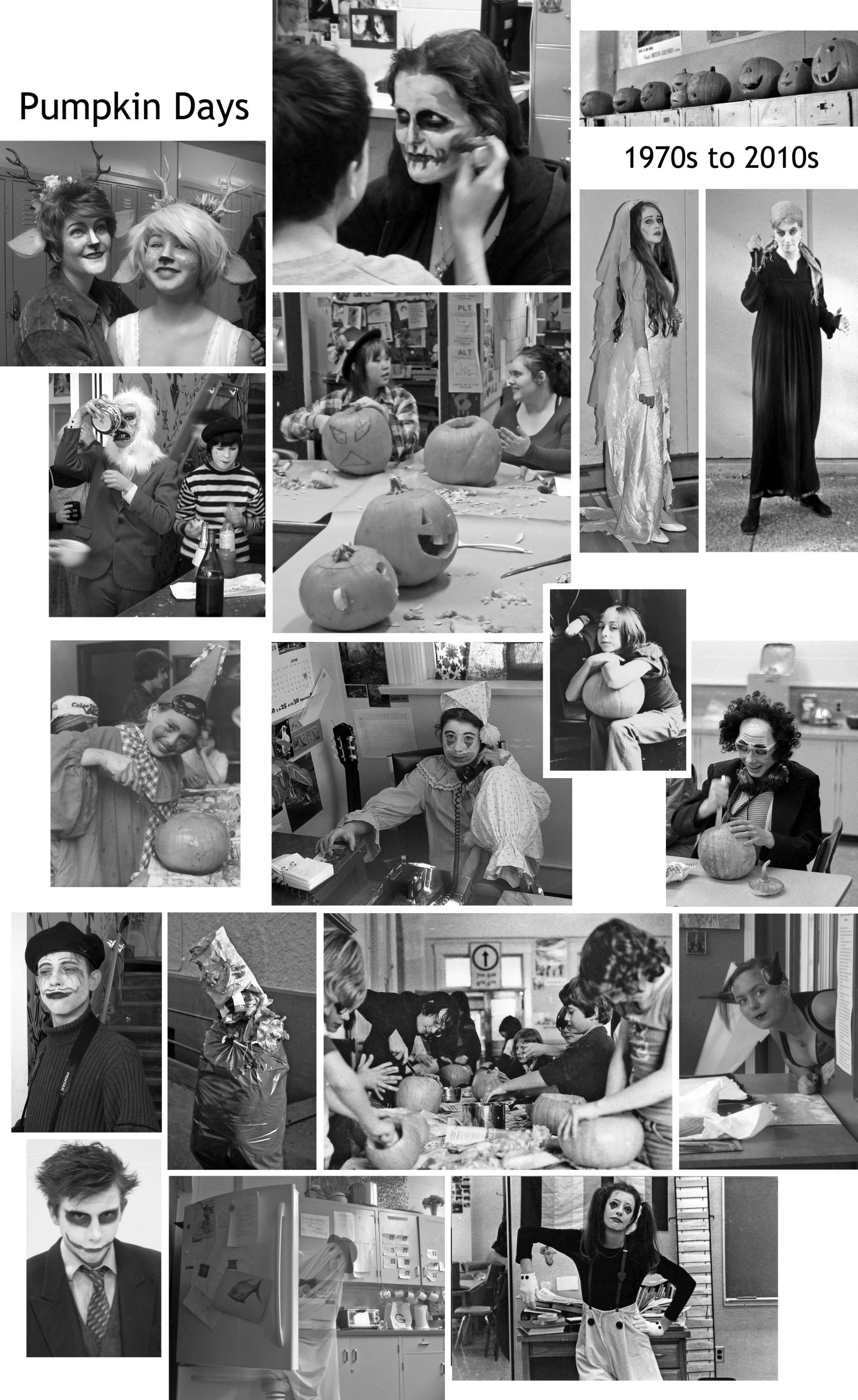

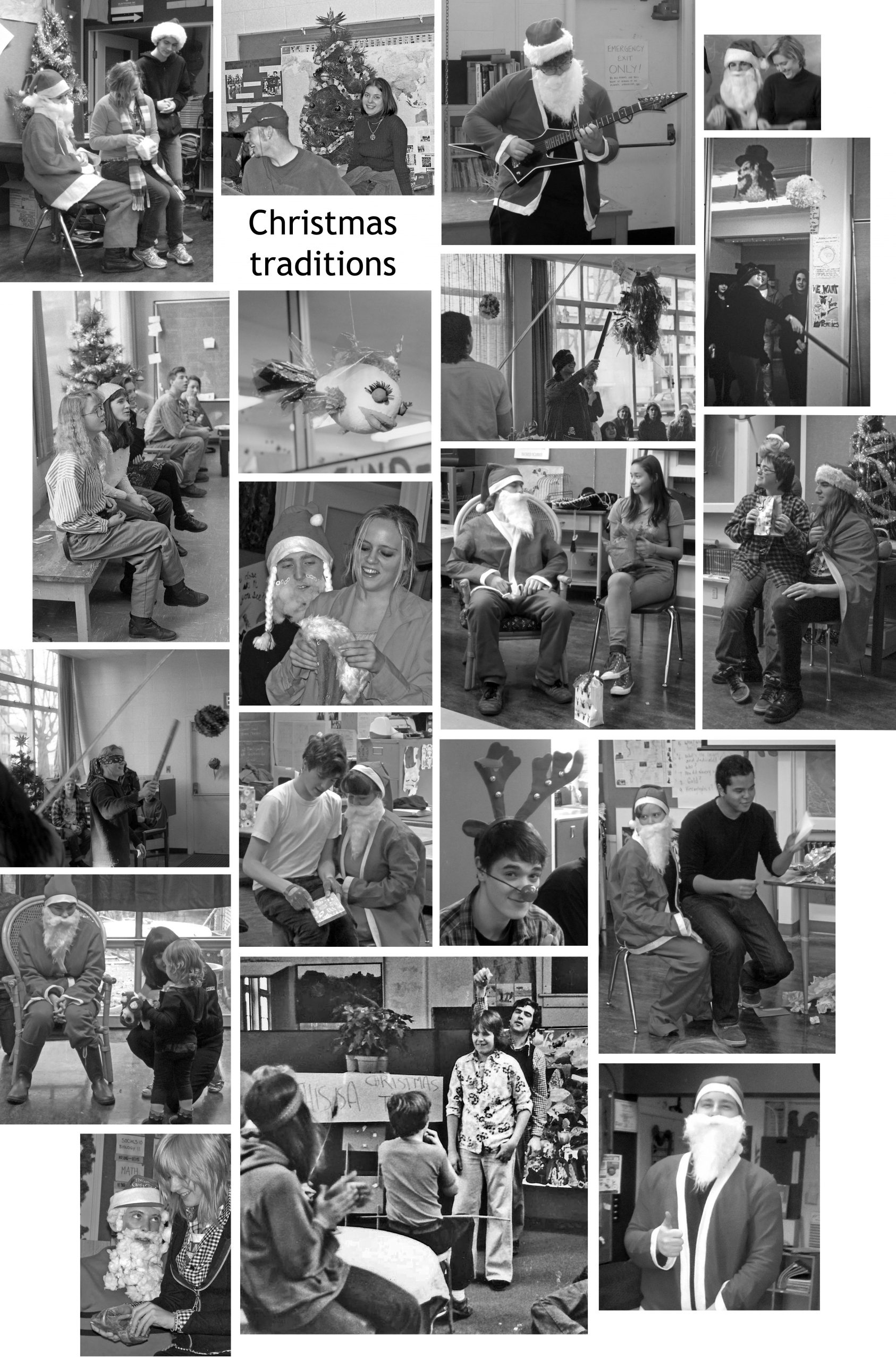

Yet life at City School went on. General meetings still happened. School traditions were upheld: Autumn Potluck Dinner, Halloween Fine Juice & Cheese Tasting, Santa’s Visit (when the most senior student would mysteriously be absent), Happy Lunches, the alternative schools’ Arts Fair, year-end camping trips, grad dinners. The garden would be tidied up and replanted; the guitars would be restrung. A postcard might be received from Norman Gazebo[35]. Some big projects were undertaken that required the cooperation of the entire school community. These included student exchanges to Quebec, Saskatchewan, and the Northwest Territories, another geology trip, and biennial Bamfield trips.

City School’s 2006-2007 brochure described the scope and flexibility of course options:

The desires of the students dictate the course offerings to some degree. As a small school, we cannot offer as wide a range of course options as are found in a regular secondary school, but we ensure that university entrance requirements may be met. In addition to the core academic courses (English, Mathematics, Social Studies, Science), students take the provincially prescribed courses for their grades (Planning, Applied Skills, Fine Arts, Physical Education). Spanish is our language option.

We are semi-semestered; that is, courses may run a full year or only one semester. Some course modules, especially in Drama and Fine Arts, may last one or two terms.

A variety of senior courses may be offered over a two-year period, including Biology 11/12, Law 12, Comparative Civilizations 12, Earth Science 11, Geology 12, History 12. Students may gain credit in courses not listed above by making special arrangements with the staff.

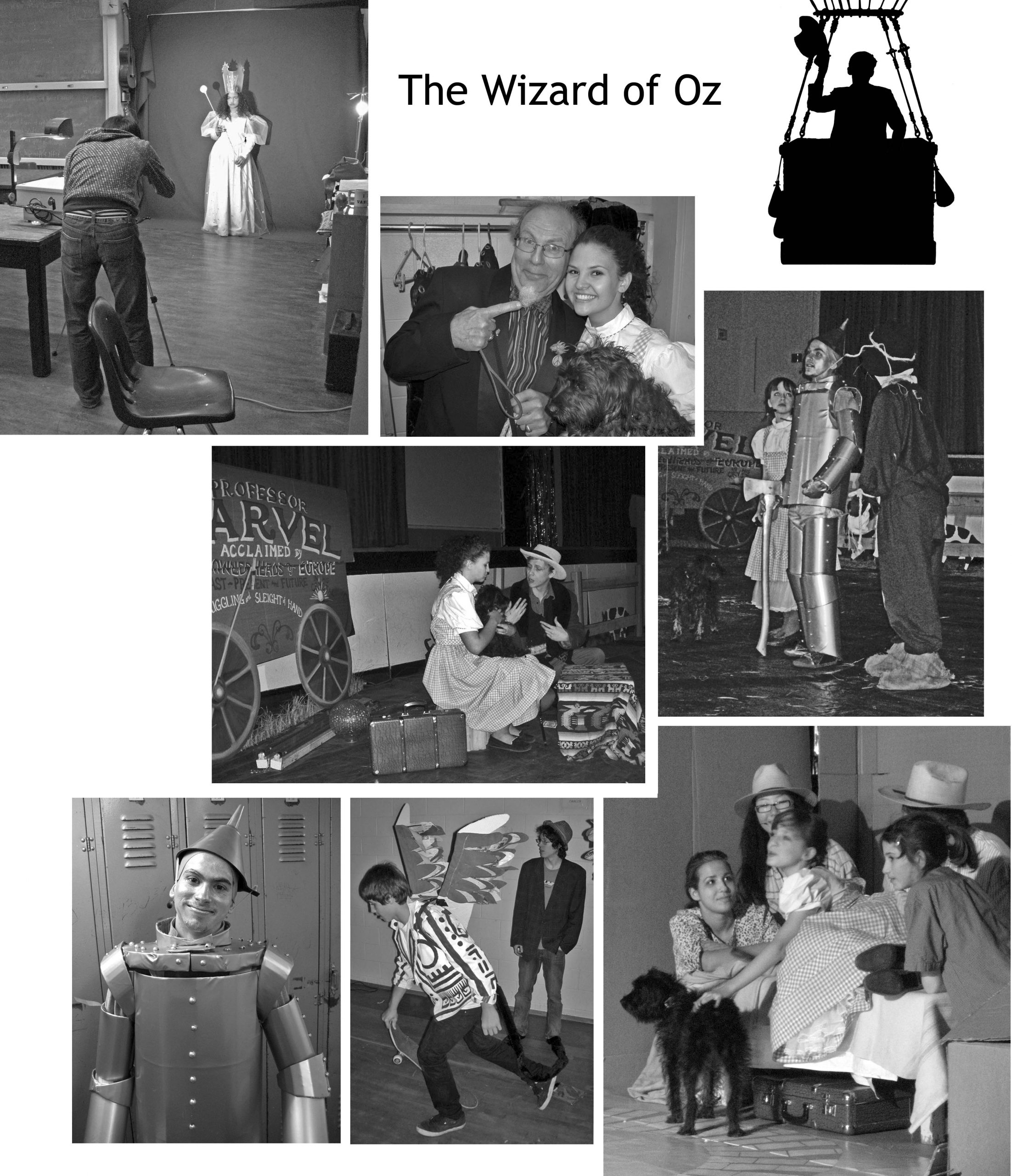

September 2007 saw a staff change that would result in four years of a solid team. Sal, now an alternative program worker, was still there. Gary Davis, then in in his fourth year, had had years of experience in alternative education, including having run his own school. Under his mentorship City School developed a drama and music focus that appealed to many students who were active in the arts outside of school. The new teacher, Jay Hildebrand, had come to education from a career in science. There was a productive variety of talents and interests among the staff and among the students. The 2009 production of The Wizard of Oz was a huge project. Every City School student and many from King George and Lord Roberts Elementary were involved in this unprecedented cooperative effort.

The 40th Reunion

Souvenir mug. Forty panels of photographs, lists of students and tidbits from our archives await reunion guests.

In the fall of 2010 the City School community – current and former – geared up to plan a celebration of its first forty years with a reunion the following May. A message went out to all who could be found online and through old address lists, inviting them to come or at least to send greetings and memories:

What do you remember about City School?

- general meetings

- camping trips

- music nights

- moving the school

- Playhouse performances

- complaining about the kitchen

- road trips

- the office door

- Wednesday lectures

- craft fairs

- Happy Lunches

- making yearbooks

- mock trials

- car washes

- taking on the school board

- exchange trips

- drama productions

- potluck dinners

- Bamfield trips

- grad celebrations

Some eighty former students – including five from the first year – and staff came and dozens more sent messages. In a giant general meeting, all had a chance to speak about what City School meant for them. A participant described it in his blog:

“As the meeting was called to order, and the agenda set, a warm feeling of belonging filled the air as students who hadn’t seen each other in decades were giggly with the novelty of seeing old peers, and sharing their personal evolution from the perspective of being adults. Introductions were called for and one after another each student and teacher introduced themselves and gave a brief biography of their life since City School. A common theme began to develop in all their introductions, City School was a special experience for all of them in their development. Students representing the many diversities of Vancouver claimed they would have been lost in a larger school setting. Teachers spoke with strong feelings about their experiences with the students and how much they grew with the students. City School offered students and teachers something which their local neighbourhood school could never offer them. Above all, from all the testaments of previous students, City School fulfilled the need for students to belong.”[36]

The themes were consistent, and experiences from 1971 could as easily have been related by people from 1981, 1991 or 2001. They remembered being alienated in their former schools, and how stepping through City School’s door made them feel they were “home.” They contrasted the subservient role imposed on them in mainstream classrooms with the respect and trust they accepted from adults at City School. They spoke of the freedom from judgment, from time constraints, and from limits on the scope and depth of what to learn. Many said they never would have finished high school, or stayed in school so long, anywhere else. The current students, as at the 1996 reunion, understood they were part of something extraordinary.

A former student who couldn’t attend the reunion got in touch later with a generous offer: to establish a fund such that no City School student need worry about paying for course supplies or activities like plays. From 2011 on, support from Hollyburn Properties has been a lifesaver for City School’s mandated use of “the city as a classroom.”

The reunion’s success boosted the energy required for challenging times ahead. The number of students remained comparatively stable even after the next staff change resulted in a less constructive team. But the pressure of unending budget cuts was relentless, and City School was continually in danger of staff downsizing or outright elimination. The former came to pass despite a heroic fight in the spring of 2014.

The VSB’s preliminary budget for 2014-15 proposed to cut the district staffing entitlement for City School in half. As reporter Jenny Peng put it, “A downtown mini school is clinging to life as school board cuts threaten to reduce the number of City School teachers from two to one.”[37]

A committee of City School parents, students, former students and staff immediately began planning on how to keep this from happening. An online petition gathered 600 signatures. Letters from former students, parents, student support professionals and the community at large were solicited and forwarded to trustees. Briefs from individuals and on behalf of the parent group were presented at VSB budget feedback meetings.

But City School was a very minor player in the budget debate, as Global News reported:

“Alumni and staff of an alternative mini school in Vancouver are speaking out against proposed cuts to teaching staff. The cuts come as part of the Vancouver Board of Education’s proposed 2014-2015 budget, which is projecting a $28.7 million shortfall. The proposal includes cuts across the education system, including the elimination of the elementary school band program, the closure of Roberts Adult Education Centre, reducing psychologist and counsellor staff and cutting teachers, including one of two from Vancouver’s City School.”[38]

While the cost of one teacher was too small to be considered even a drop in the half-billion dollar bucket, the impact on City School was life-altering.

A morning of serenity in anxious times, January 2014.

Part VI – from September 2014: “Urban Renewal”

A school with one full-time teacher plus one half-time alternative program worker could not function as it had with a second full-time teacher, offering a complete graduation program to students in Grades 10, 11 and 12. And it shouldn’t have had to. When City School moved to King George in 1980, it brought a “district staffing entitlement” of two teachers with it. At that time, City School had more than enough students to merit two teachers; the district entitlement went into the King George staff numbers, and there it stayed. The truth of this peculiar arrangement did not emerge for many years; the City School staff knew nothing about it. The funding formulas grew so complex and arcane that by 2014 every teaching block was gold. Somehow, when the district entitlement was cut from two to one, it was City School’s staff that took the hit. For the 2014-2015 year, a single block of teaching time would be made available to City School from the King George allotment.

How was it possible to carry on? The staff was realistic enough to know something major would have to change. The way forward was to go back to the founding philosophy and let the education fall where it may. The motto of the day was “Classes if necessary, but not necessarily classes.” From promotional material early in the new regime:

The school day starts with Advisory (individual meetings with staff, parents, whoever) from 8:30 to 9:00, then Fundamentals (primarily time for honing English and math skills) from 9:00 to 10:30. General Meeting (organizational get-together) comes next. The rest of the day, usually until 3:00 or later, is a variety of field studies, projects, guest speakers, seminars and other activities that have been planned – or pop up spontaneously – to support learning goals. The last half hour is set aside for Reflection (students document their activities and reflect – what I did, what I found out, how it relates, what I’m wondering – on the progress they’ve made that day toward their goals). This schedule is our default; we modify or suspend it if there is something better to do, such as an all-day trip or conference, or if we’ve been out late the evening before.

Students are responsible for making sure they know where and when they are supposed to be on out-trips, and they must be accountable for their whereabouts every school day.

The relationship that had been “sponsor-student” in the early 1970s was rebranded “advisor-student”:

You choose the staff member who will be your advisor, and meet as often as necessary to get and stay on track. Our Advisory time most mornings is for such meetings.

Your advisor helps you figure out what you need to do in order to achieve your educational goals. Your advisor is responsible for providing educational guidance, helping you plan, recommending courses and projects, offering strategies, and following through and tracking your progress with you.

On what students could expect:

Our name comes from our mandate: to use the city as a classroom. Vancouver – and the Lower Mainland – is full of people, places and things that are real-world manifestations of what the textbooks tell us. Musicians, scientists, writers, historians, entrepreneurs, artists, politicians, specialists of all kinds: these people are our resources.

Students familiarize themselves with the provincial Prescribed Learning Outcomes (PLOs) for each of their courses. They review them regularly and strike a balance between PLOs and our RALs (Random Acts of Learning).

Students maintain their own records of their learning, meet regularly with their staff advisors, and produce detailed self-evaluations at report card time.

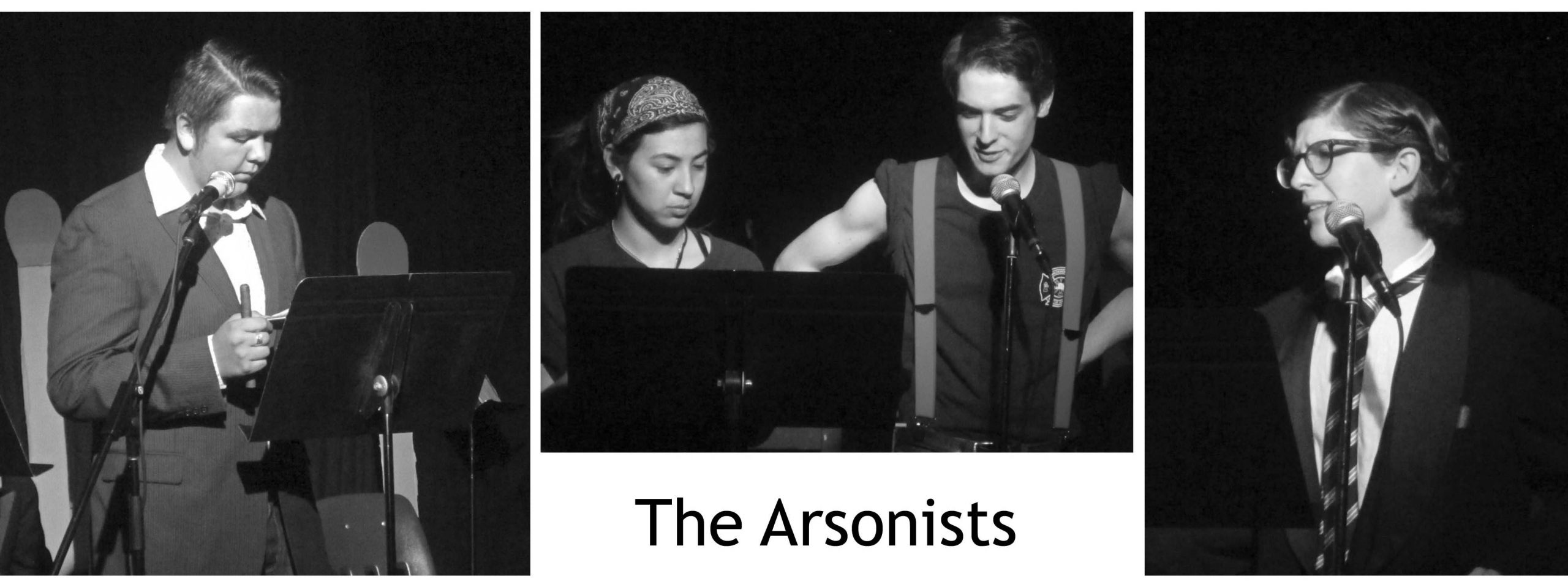

A year-end summing-up of how City School had met its mandate noted that in 35 weeks of school, there had been 65 “times we used the city as a classroom, not including group project related activities”: four full day conferences/events; five films; thirteen guest speakers; sixteen outings with specific curriculum connections; sixteen outings of general interest and eleven theatre performances. Four group projects of three or more weeks’ duration included creating walking tours of the West End as it was in 1915 and a fundraising drama production undertaken entirely by students. 225 hours of Fundamentals time had been scheduled for self-paced work on academics with teacher help. Journaling for English courses required 9000 words of writing from each student. While the evaluation/assessment aspect of the enterprise was onerous and would need some tweaking, the general feeling about the school’s new format was positive. The phasing out of provincial exams made for greater flexibility. Students earned credit in 21 different courses.

Hands-on learning at Vancouver Archives. “Geneskool” at Capilano University.

The next couple of years followed a similar routine. But with no time in the schedule for the staff to meet, any planning and organization had to be accomplished outside of school hours. The eagerness to do this abated after many months and a series of staff turnovers began.

Continued lobbying for a second full-time teacher had been fruitless. But it resulted in a suggestion from the VSB in early 2017 that City School withdraw from the category it shared with mini schools and throw in its lot with the alternative programs. The advantage would be that their different staffing formula would increase the number of adults working in the program. By spring 2020, this move was being planned for the fall – City School’s fiftieth year.

PART VII – The Legacy

Leading the way.

In its five-decade history, City School pioneered initiatives, such as using the city and beyond, that later became policy at the provincial level and now appear in Ministry of Education documents: “Learning can take place anywhere, not just in classrooms.”[39] “Students benefit from more flexibility and choice of how, when, and where their learning takes place.”[40] The concept of “sponsor” was key from the very start: “Teachers will act as guides and coaches for learning.”[41] “As our education system continues to evolve, the teacher’s role is shifting from information provider to facilitator – a professional who helps each student learn how to learn.”[42] City School students designed their own courses years before Independent Directed Studies formalized the process. Opportunities for developing “cross-curricular competencies” were built into City School activities decades before the term made its appearance in B.C. education literature.

Many hundreds of students, parents, staff and administrators have been responsible for the direction, success and survival of City School, far more than can be mentioned, but it’s fair to acknowledge those individual members of staff whose commitment to making it happen endured for five years or longer. They are Sue Arundel (5 years), Joanne Broatch (5), Alan Crawford (5), Gary Davis (7½), Caroline Dixon (9), Kit Fortune (5), Thom Hansen (5½), Thomas Harapnuick (9), John Henderson (11), Jay Hildebrand (10), Jennifer Luis (9) and Sal Robinson (41). One student enrolled in Grade 4 and stayed until graduation; his record is exceeded only by that of Norman Gazebo.

June 2020

PART VIII – Sampling the Archival Record

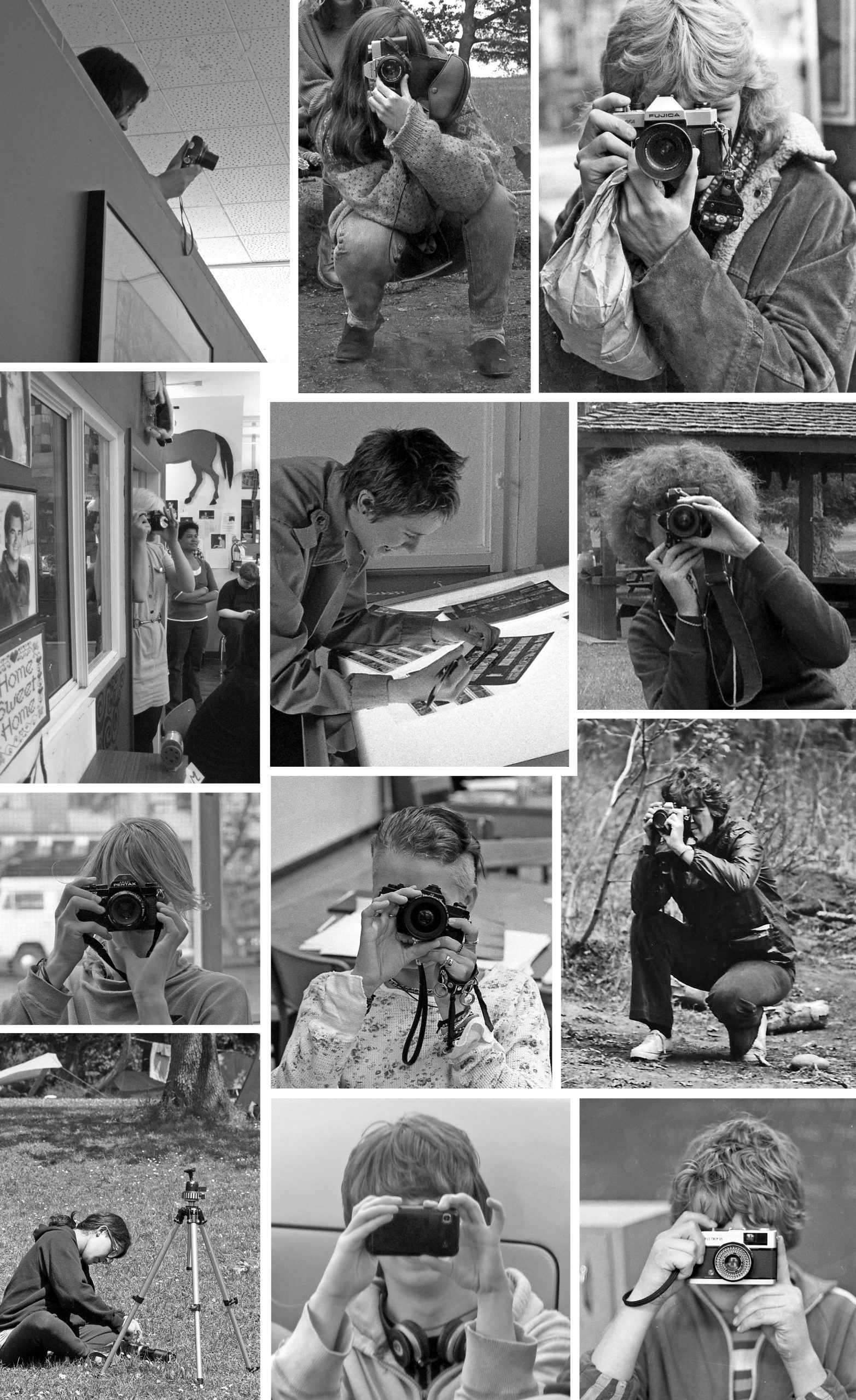

Many people spent time behind the camera and in the darkroom in the early days, and I don’t know who all of them were, but some of them taught me about photography, which skill I passed on to many more. Then came the digital era and the barrage of pixels in our inbox. If you are responsible for one or some of the photos here, I thank you for your contribution to our school and its archives – Sal.

Note: Left-click twice on a collage to magnify it.

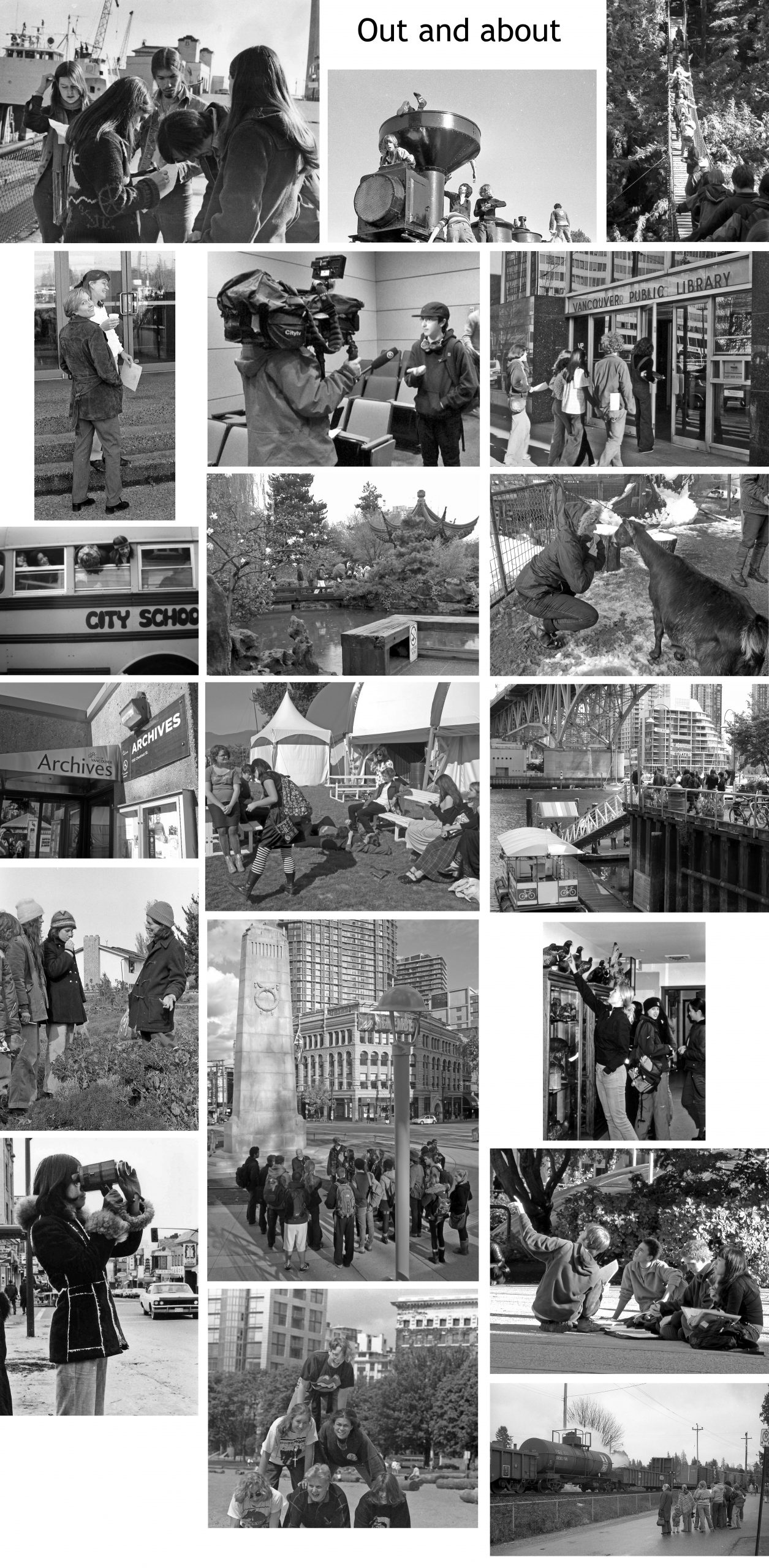

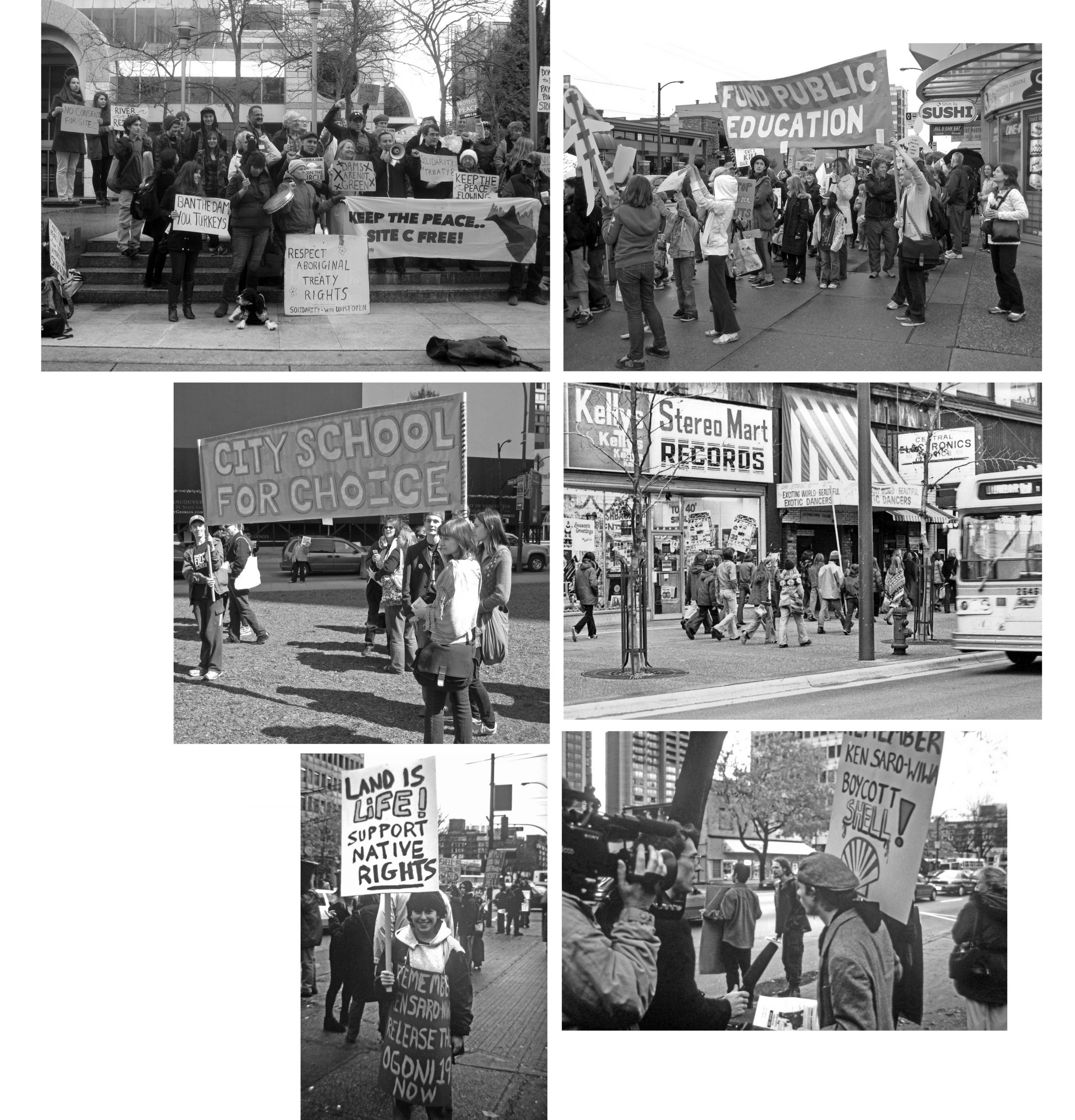

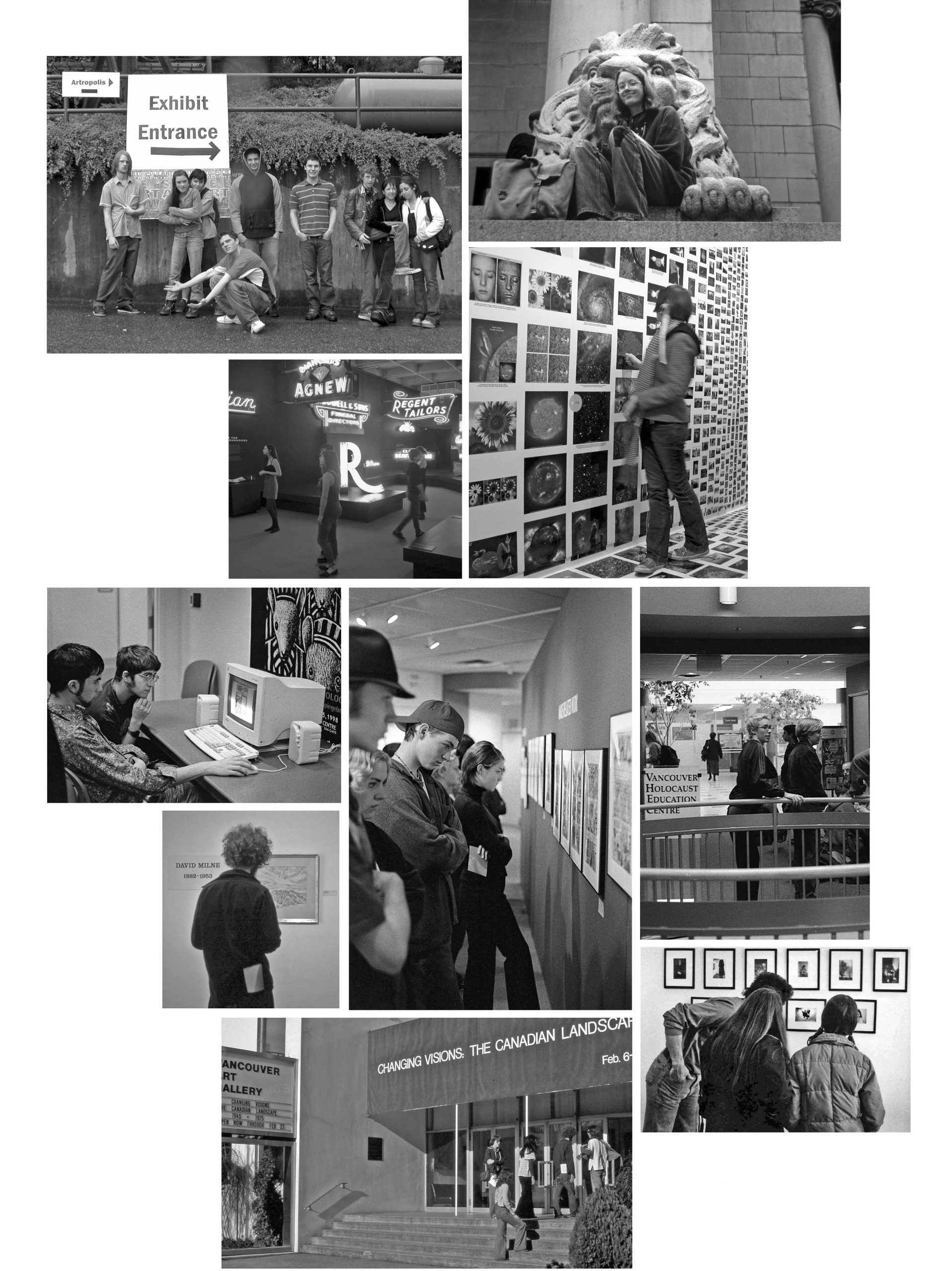

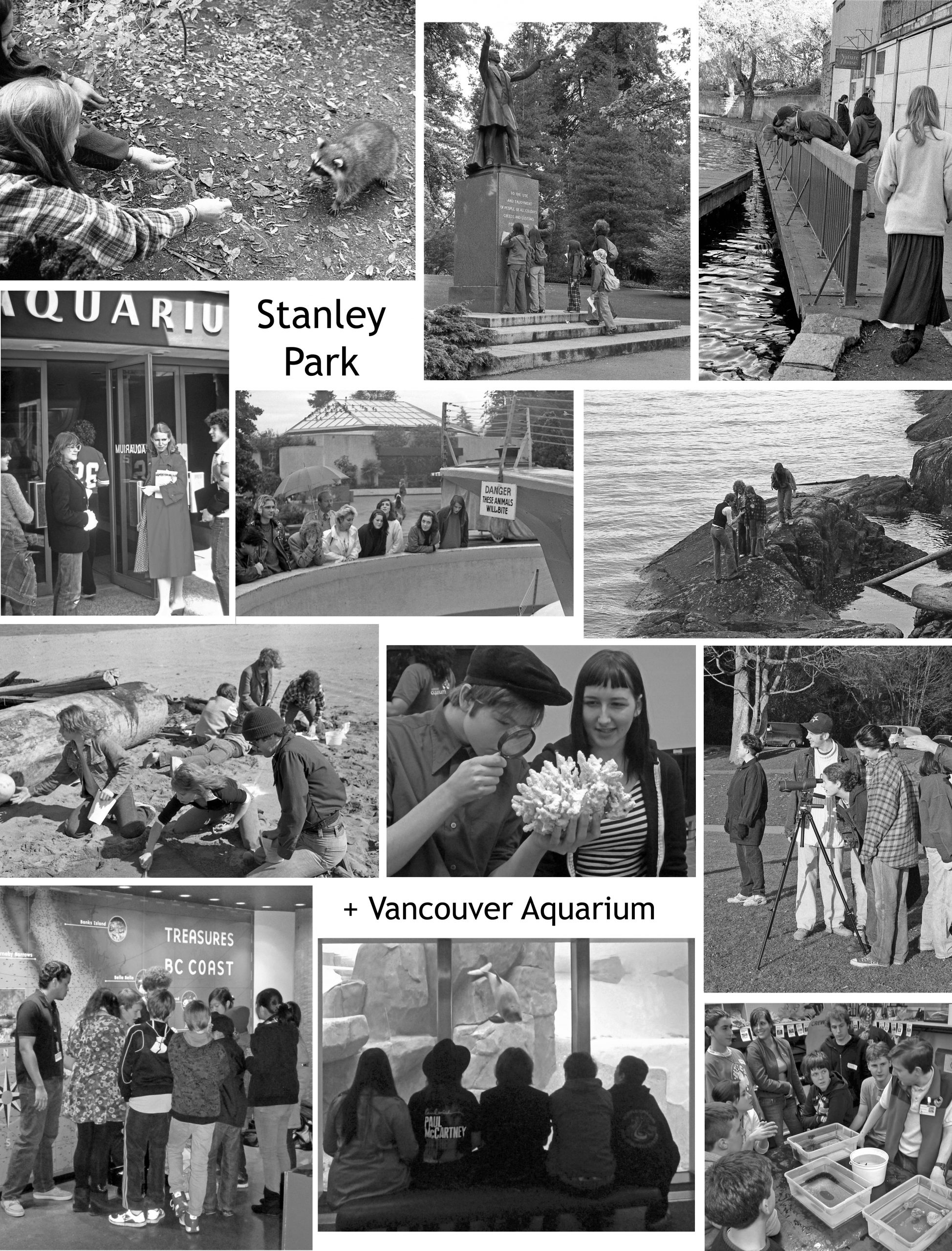

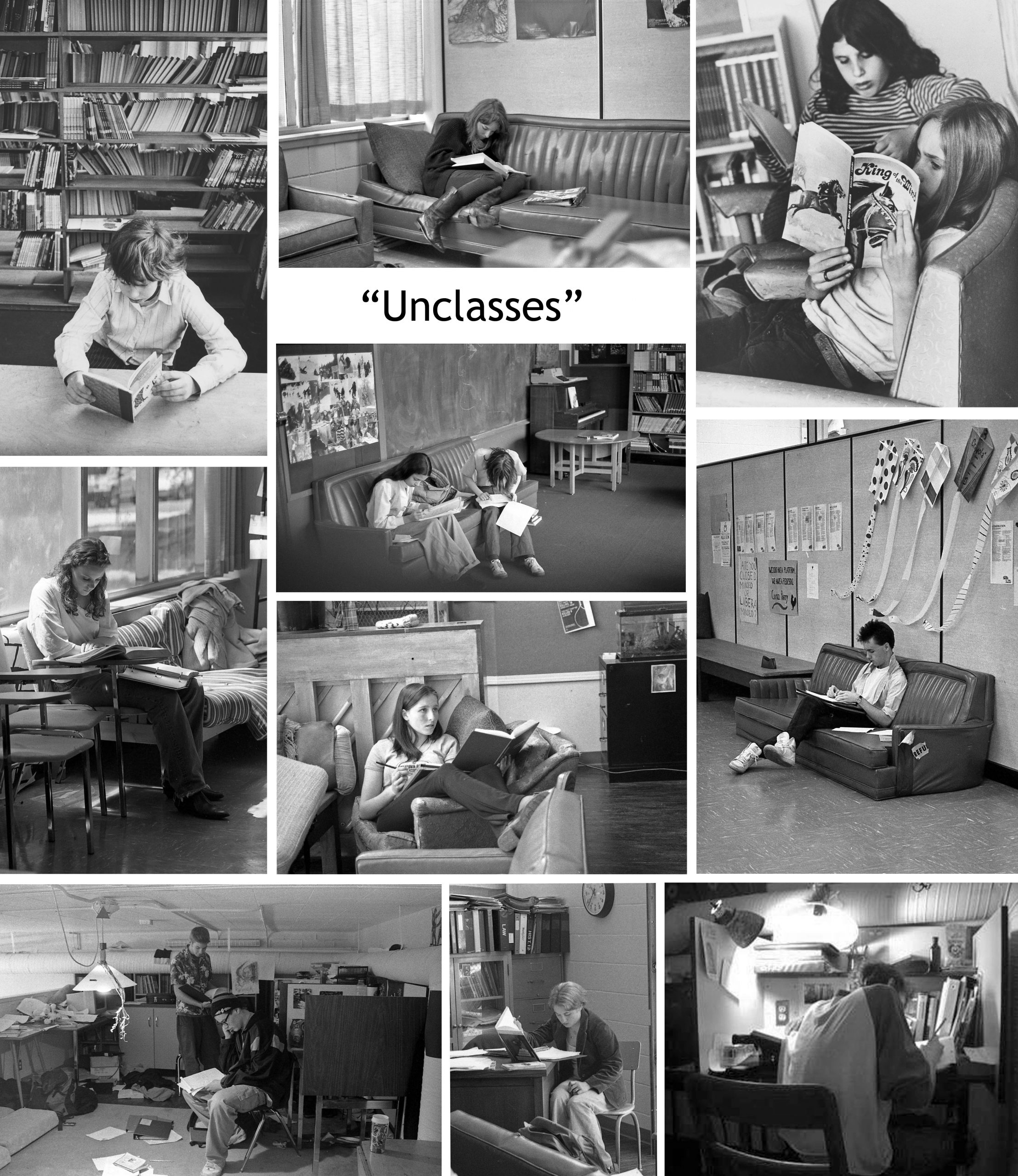

Theme One – The City as a Classroom

Theme Two – The Province/Country as a Classroom

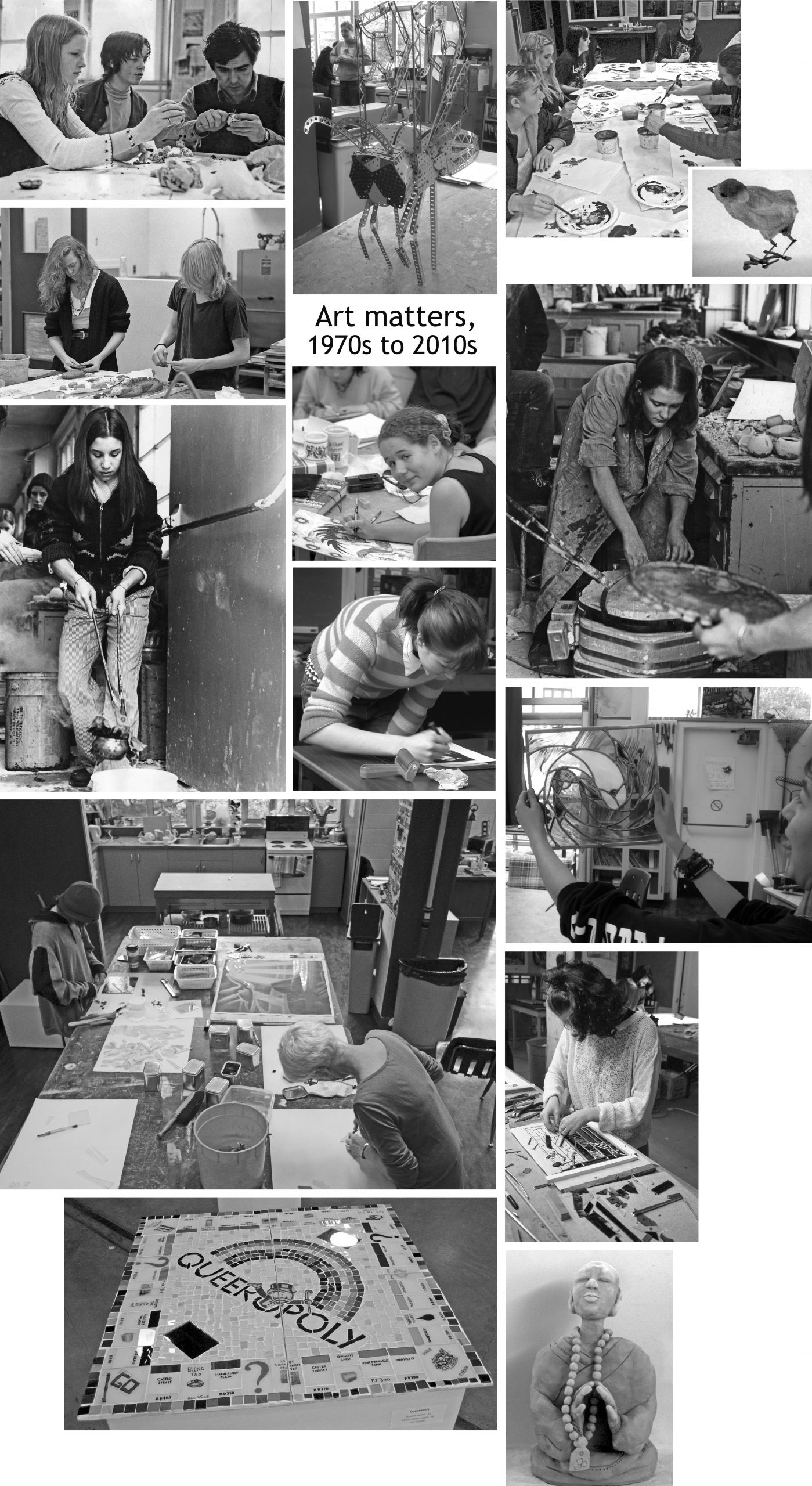

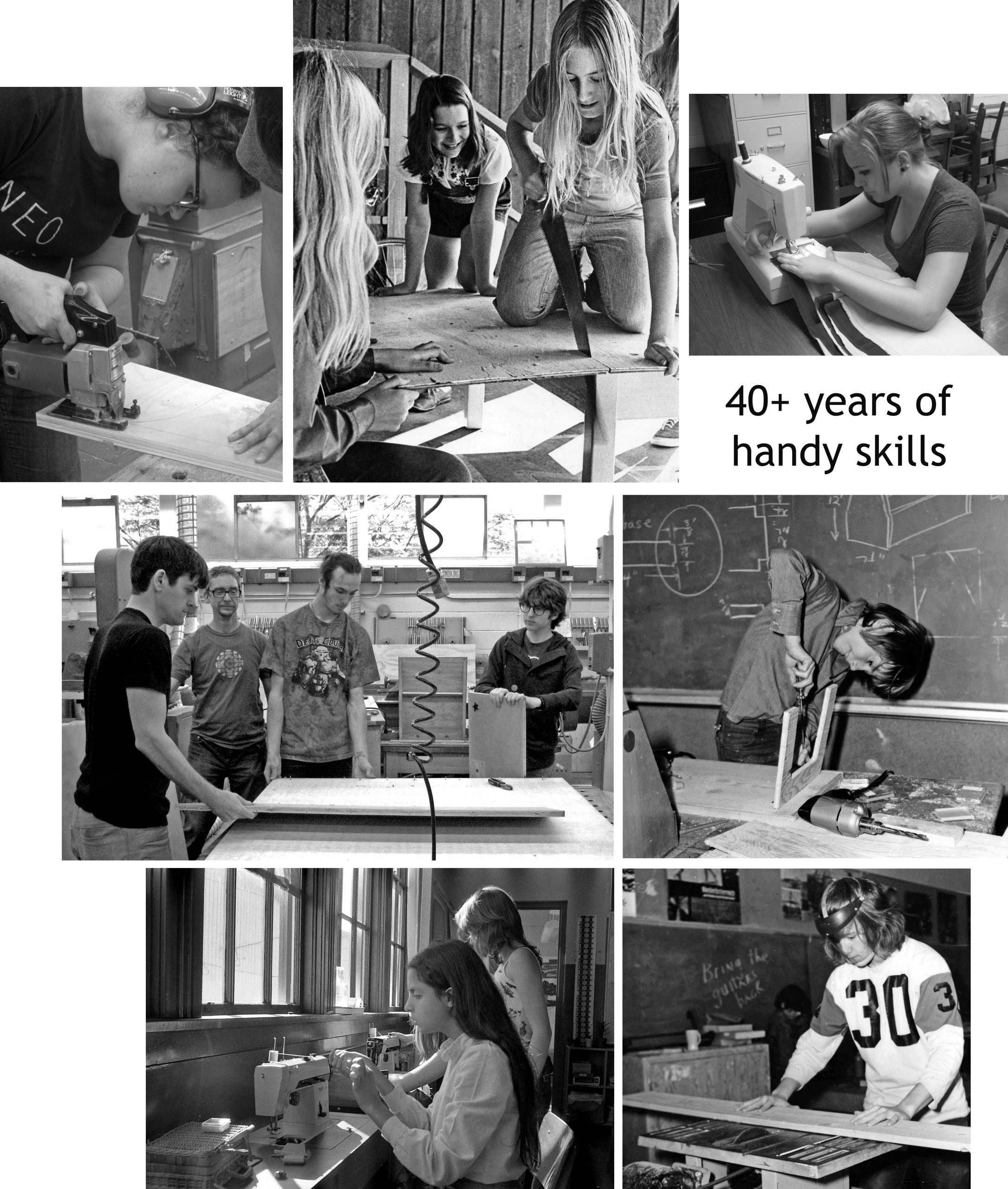

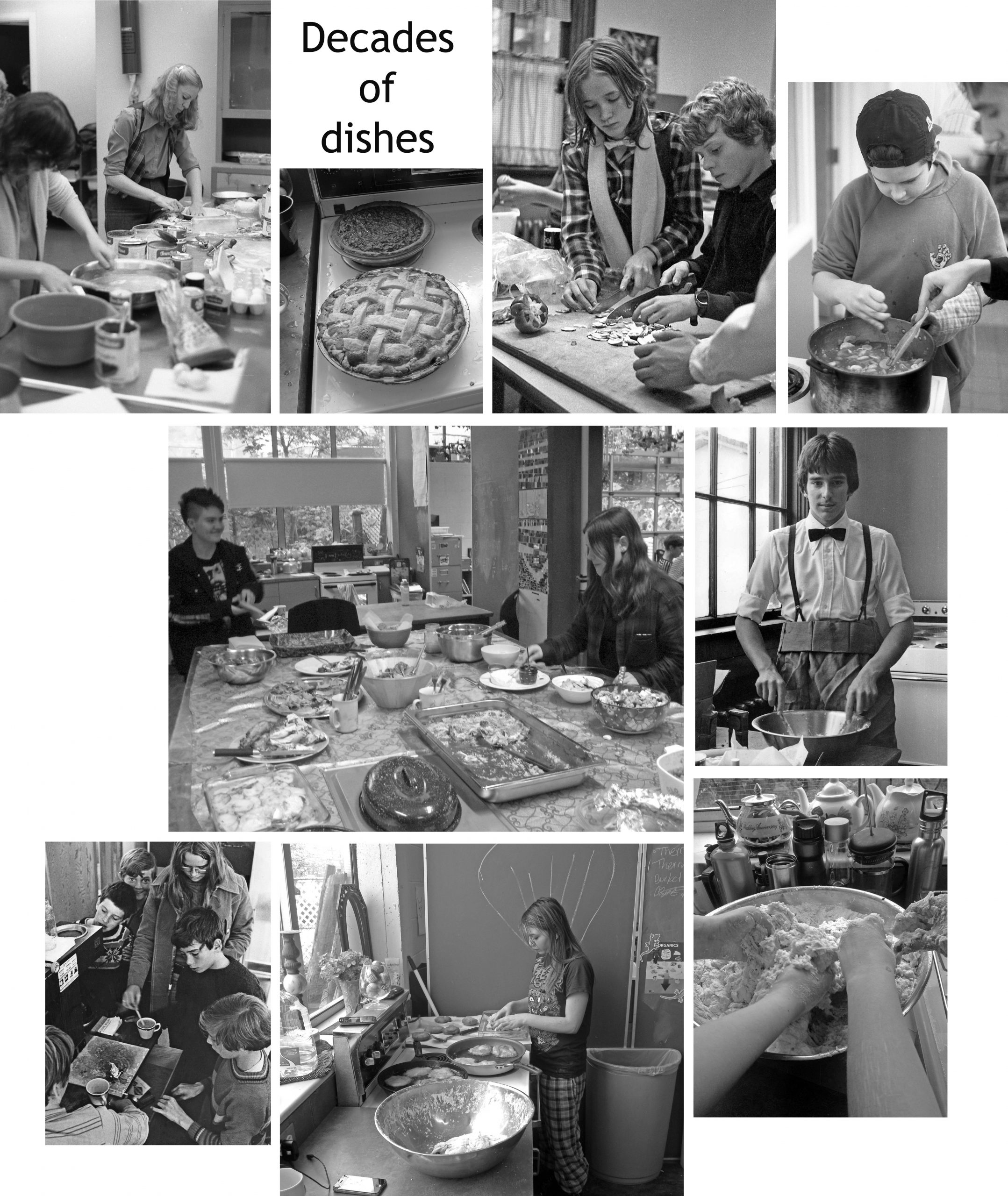

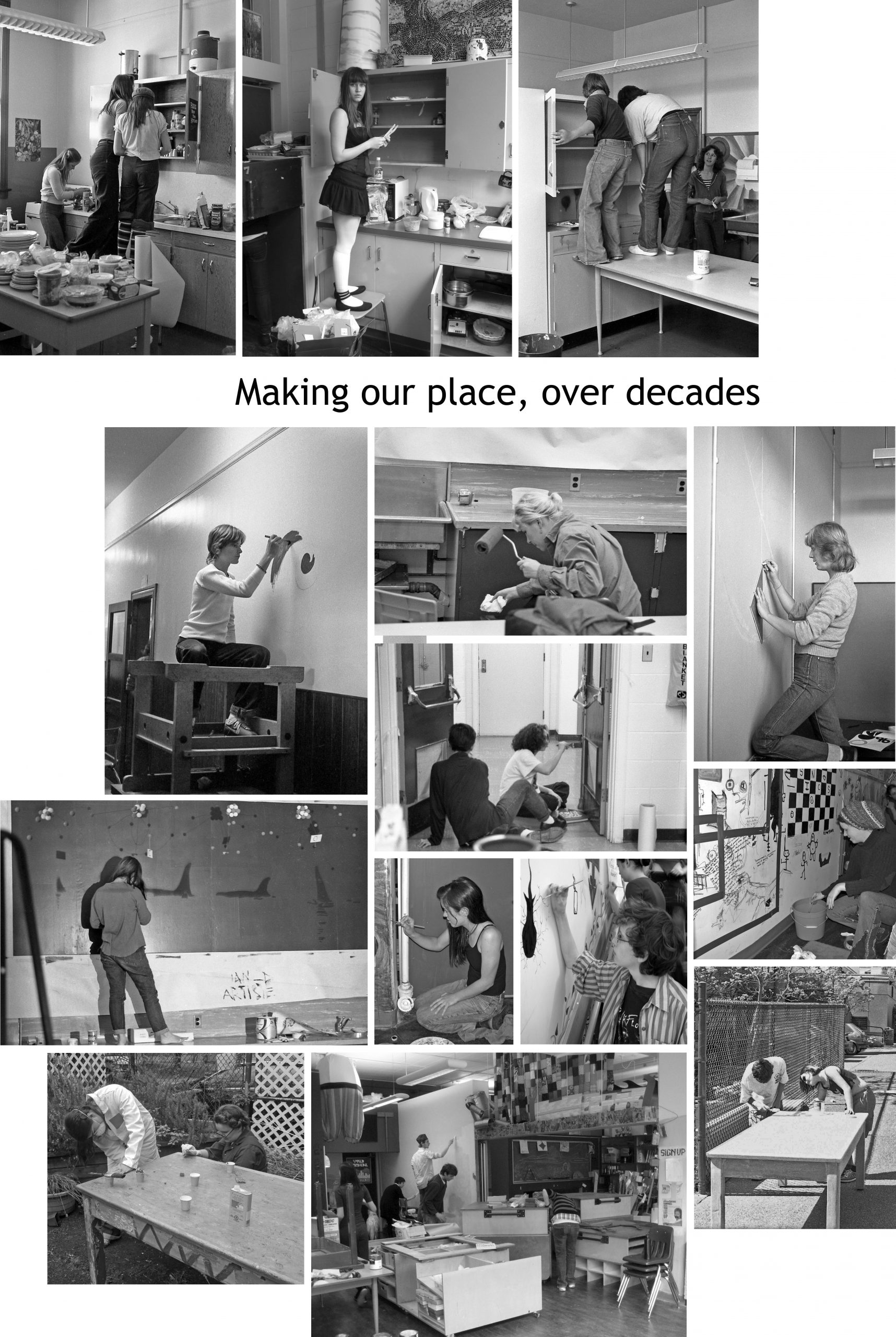

Theme Three – Making Stuff

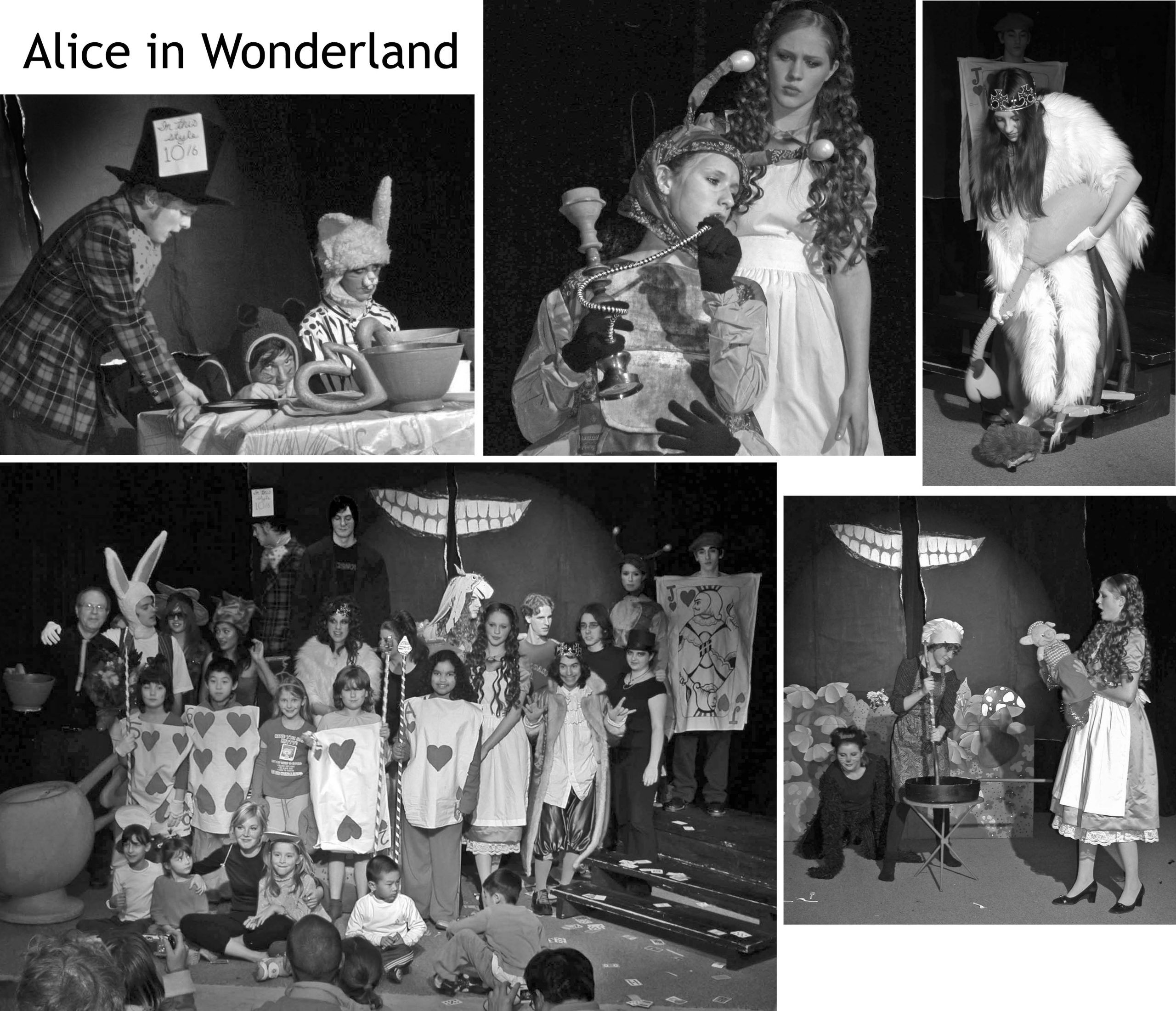

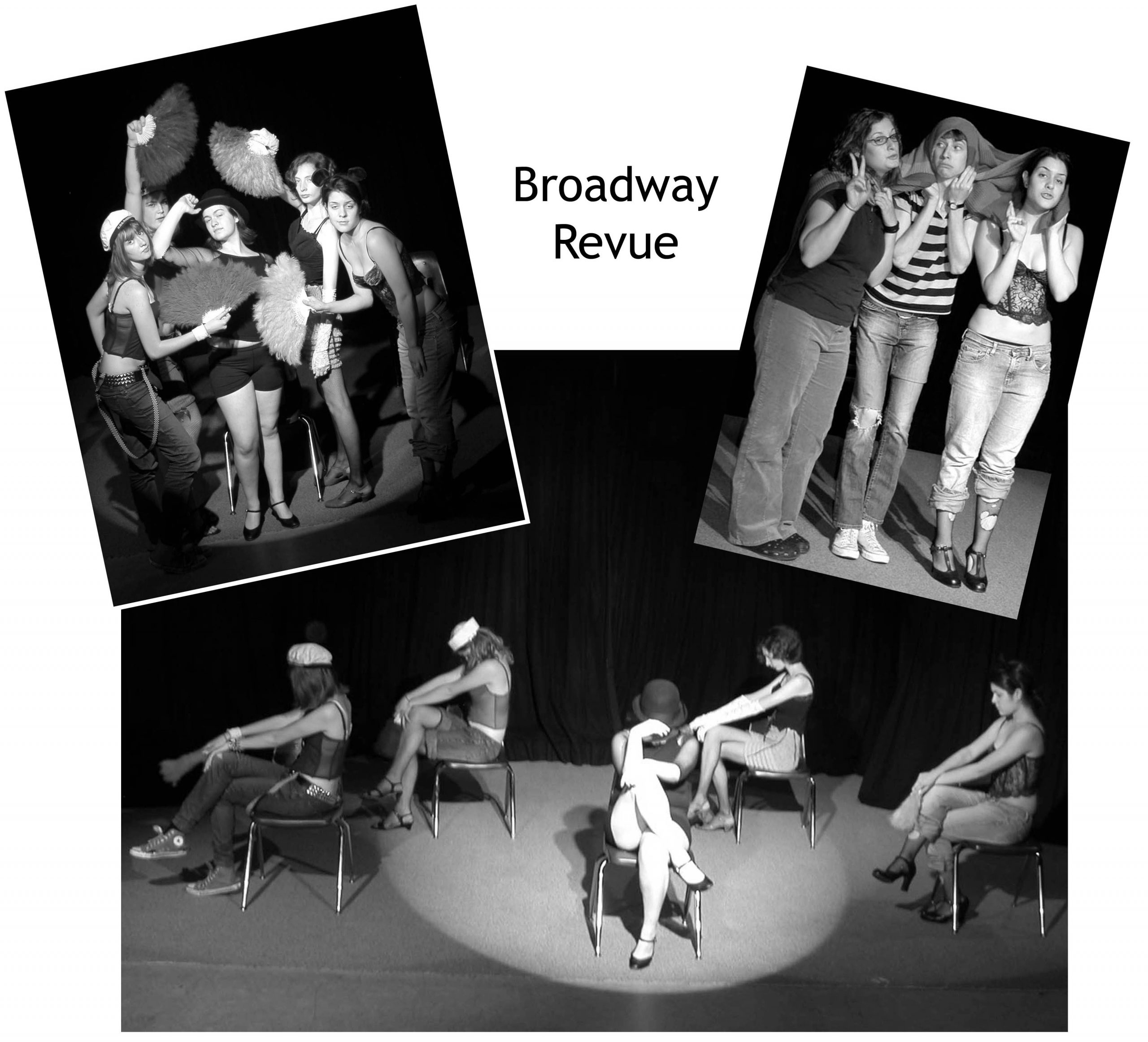

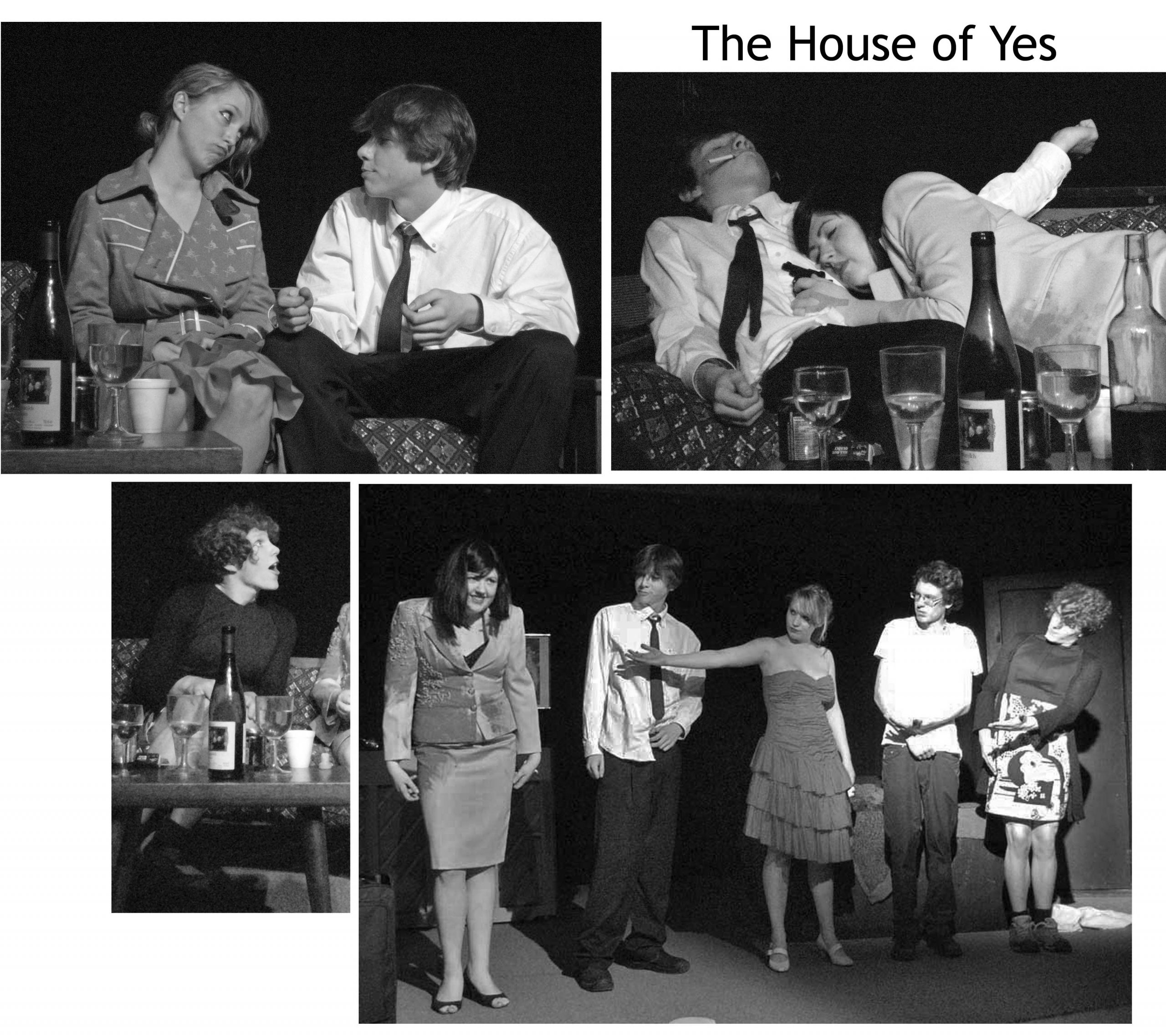

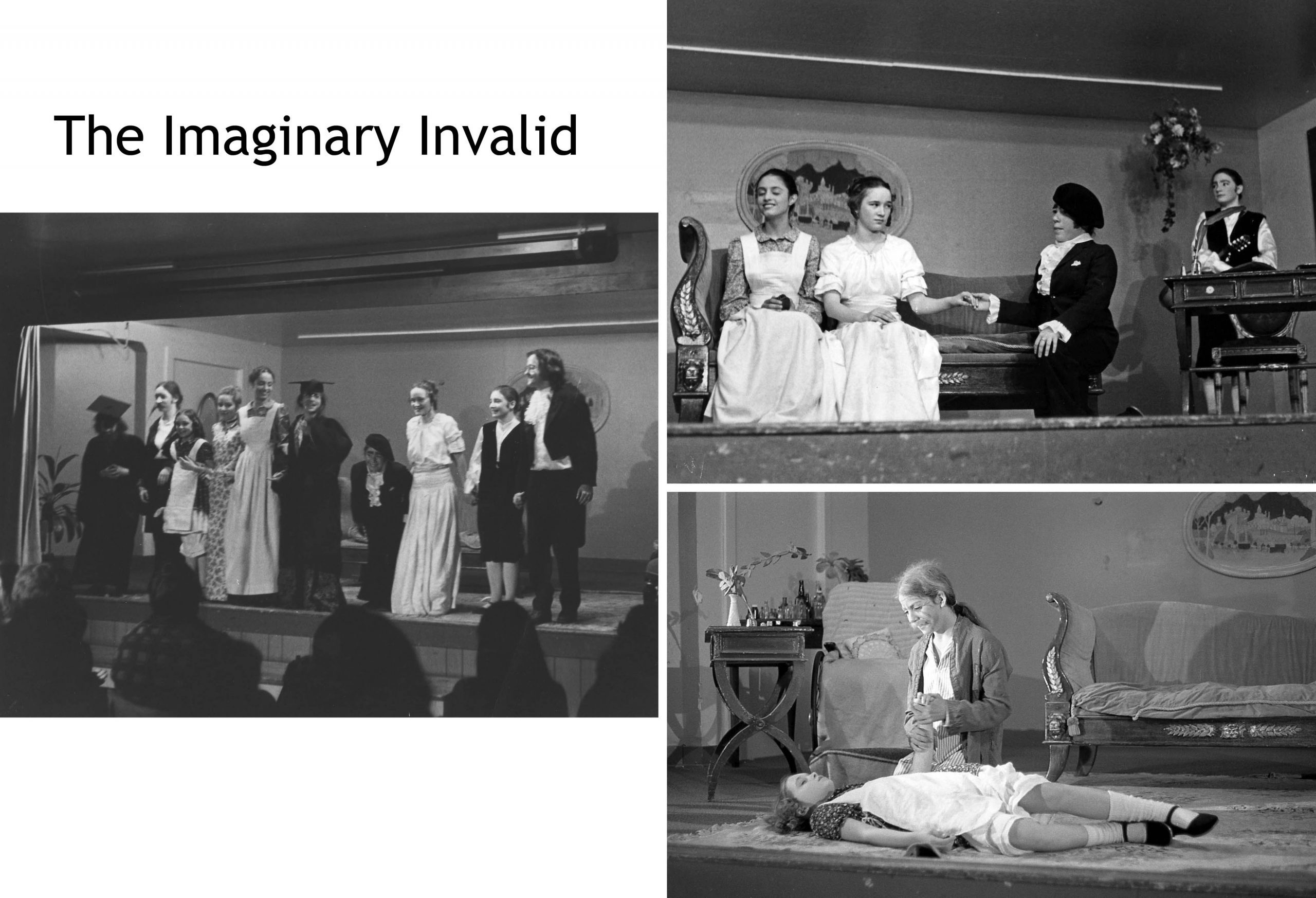

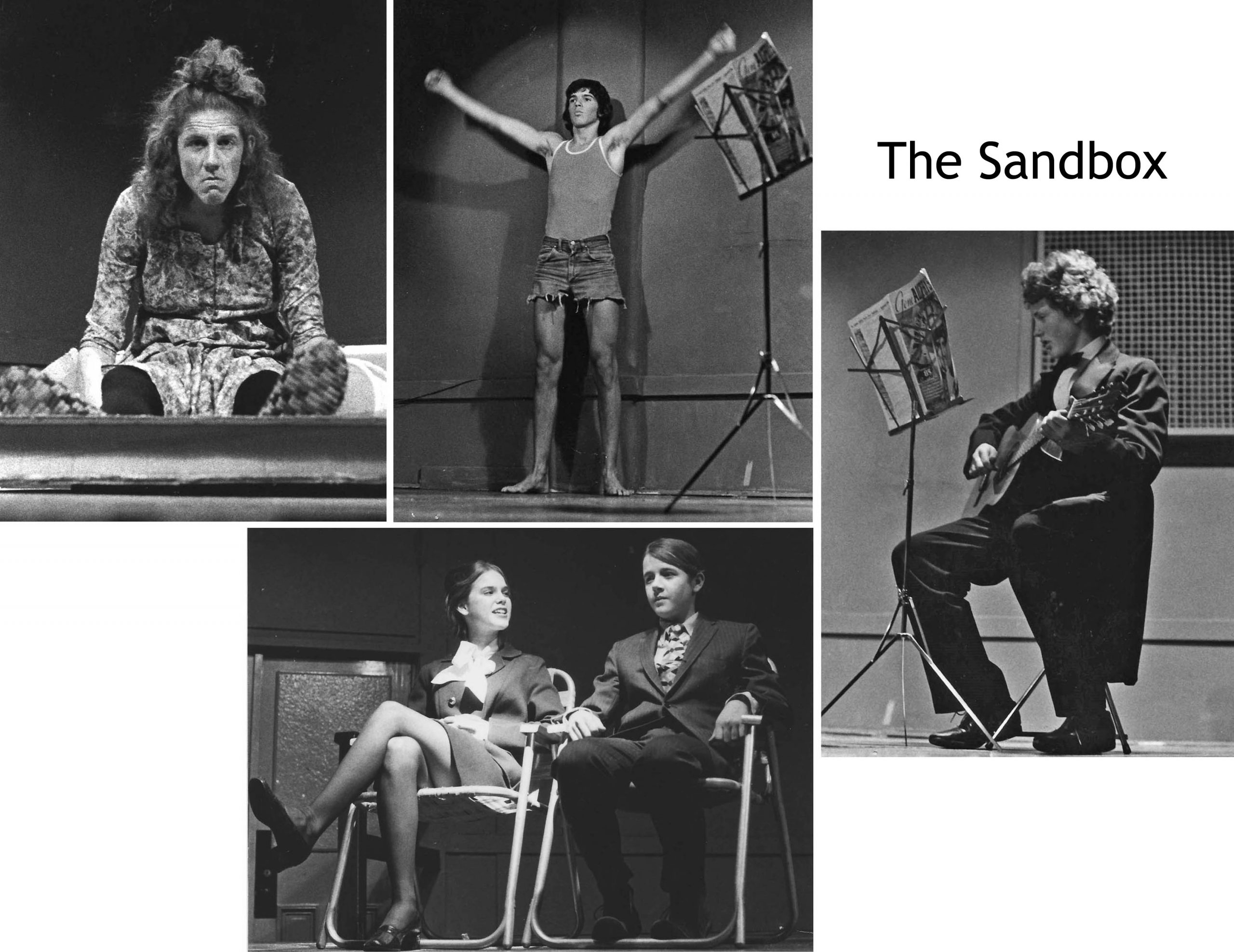

Theme Four – On Stage

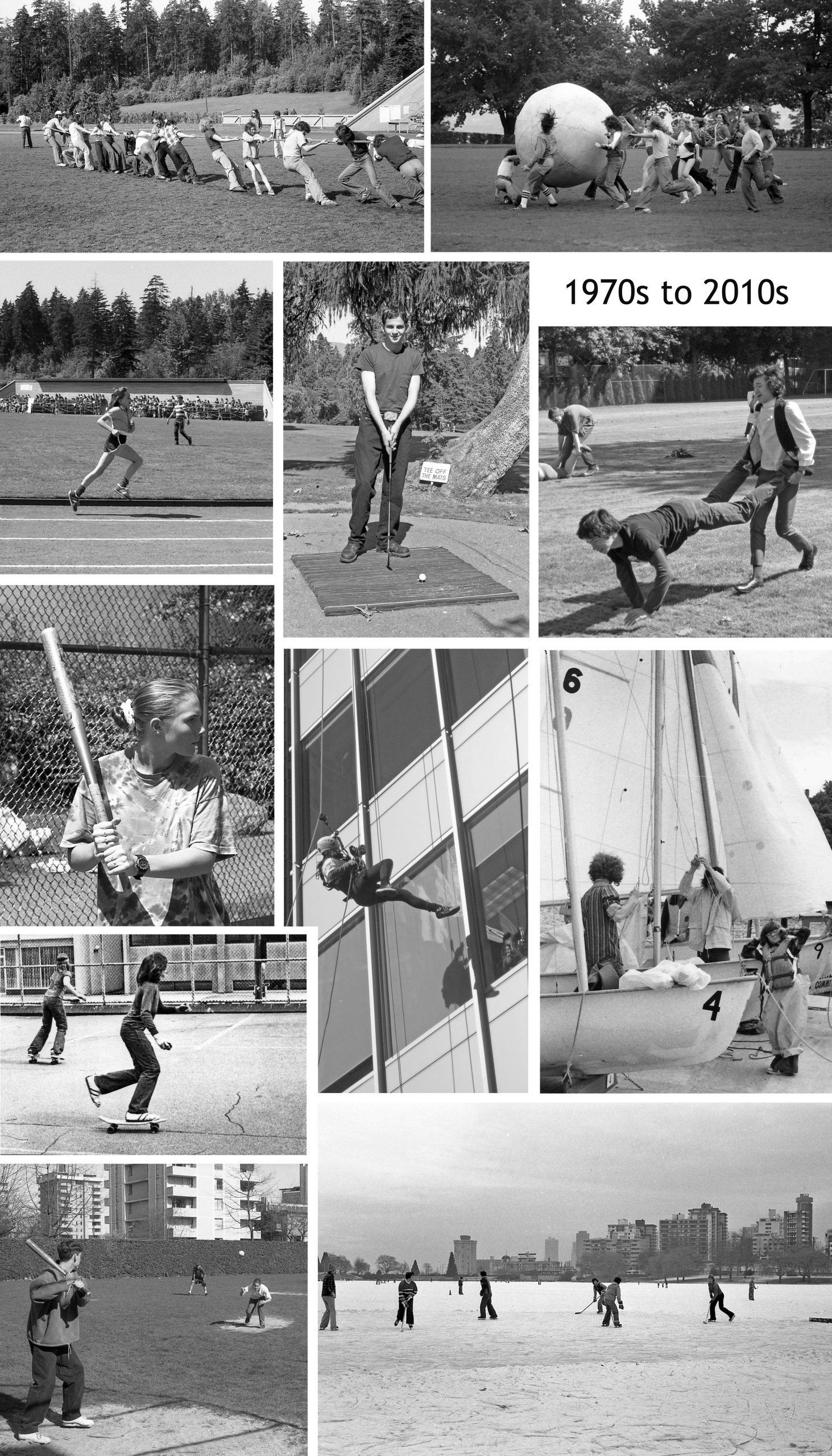

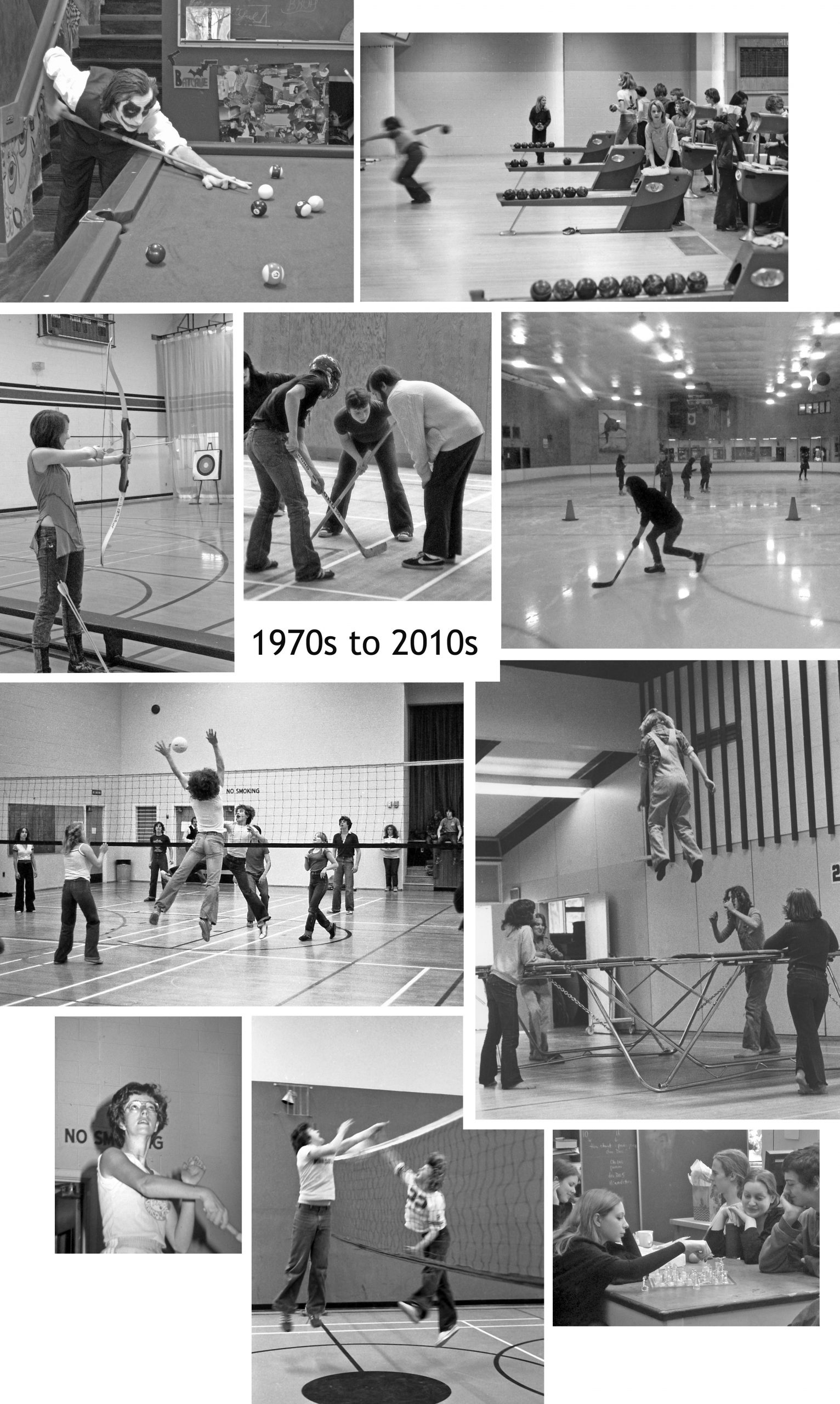

Theme Five – Sporting Life

Theme VI – Around the School

Endnotes

[1] Rothstein, Harley Stephen. “Alternative Schools in British Columbia, 1960-1975” UBC 1999

[2] The Vancouver Sun, June 1, 1971, page 10

[3] The Province, June 26, 1971, page 4

[4] The Vancouver Sun, July 19, 1971, page 4

[5] The Province, September 8, 1971, page 4

[6] Bennet, Wilf. “’A little of what you fancy’ the byword at new school” The Province, September 17, 1971, page 39

[7] The Vancouver Sun, June 6, 1973, page 7

[8] Brief to the Board of School Trustees, City School, June 1973

[9] Ibid.

[10] The Vancouver Sun, August 22, 1974, page 10

[11] McAlpine, Mary. “No tears, no pain, just learning” The Vancouver Sun, November 30, 1974, page 44

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] “About City School” brochure, 1974

[15] Ibid.

[16] “Student Commitments Required by the Student Community”, 1975

[17] Minutes of City School Annual General Meeting, June 10, 1976

[18] Krangle, Karenn. “City School wants to stay where the action is” The Vancouver Sun, October 20, 1976, page 89

[19] “Old school to be ‘phased out’” The Province, October 26, 1976, page 38

[20] “City School carries on fight against eviction” The Vancouver Sun, December 10, 1976, page 7

[21] Krangle, Karenn. “Situation is less than ideal for displaced students” The Vancouver Sun, January 7, 1977, page 28

[22] Krangle, Karenn. “Alternative schools have identity crisis” The Vancouver Sun, June 3, 1977, page 17

[23] Letter from City School to VSB Assistant Secretary-Treasurer Alick Patterson, January 24, 1979

[24] Weinstein, Pauline and Wes Knapp. “Presentation to the Vancouver School Board Regarding Cutbacks in the 1979 Provisional Budget”

[25] The Vancouver Sun, May 9, 1981, Page 9

[26] Parton, Nicole. “Playing the Money Game” The Vancouver Sun, April 2, 1982

[27] Ibid.

[28] Sharp, Anne. “Highschool students become well-informed consumers” Enterprise, May/June 1982, page 11

[29] Scott, Olivia. “West Enders plead for school” The Province, January 25, 1985, page 3

[30] Ibid.

[31] The Province, May 21, 1995, page 80

[32] Will, Gudrun. “From overseas classrooms to university preparation, enriched programs train our brightest” Vancouver Courier, October 15, 1995

[33] Balcom, Susan. “City’s school within a school keeps teens from dropping out” The Vancouver Sun, May 14, 1996, page B1

[34] Ibid., page B8

[35] Norman Gazebo’s name appeared on sign-up lists for classes and field trips from about 1973. Norman himself never materialized. His name turned up in the roster of students in several City School yearbooks – decades apart. In 2005 he was voted “Most likely to miss a field trip.” In 2014 the newly catalogued “Norman Gazebo Library for the Arts and Sciences” was inaugurated in the City School loft.

[36] Christeller, Pascal. “In Defence of City School, an Alternative Enriched Learning Environment” May 14, 2014

[37] Peng, Jenny. “Alumni rally to defend Vancouver alternative school” Vancouver Courier, April 30, 2014

[38] “Alumni, staff rally against proposed cuts to alternative Vancouver school” Global News, April 11, 2014

[39] “Curriculum Redesign” https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/rethinking-curriculum, accessed March, 2020

[40] “Vision for student success” B.C. Ministry of Education, March, 2020

[41] Ibid.

[42] “Kindergarten to Grade 12: Teach” B.C. Ministry of Education, March, 2020