Chapter One: 1872 – 1890

Vancouver School District History

Hastings sawmill built on the south shore of Burrard Inlet by Captain Edward Stamp in 1865.

“Although he would not live to see it, the visionary sawmill on Burrard Inlet that Stamp started would reign as Vancouver’s first and longest lasting industry into the 20th century, paralleling the history of the developing world of the day. It began its life producing enormous amounts of spars supplying the globe’s mercantile ships with the tallest straightest masts the world had ever seen. From the 1860s on, its timbers would build whole towns in South America, baronial homes in in Britain, Australia, and New Zealand and the Imperial palaces of China.”

(Vancouver Exposed: A History in Photographs, Donald E. Waite, Books – Amazon.ca, 2010.)

- Introduction

The first school in what is now Vancouver was built in 1872, at Hastings Mill, fourteen years before the city was incorporated. It was housed in a modest, one-room building constructed with the help of local parents. The schoolhouse is just visible in the photograph above. It is the second building in from the right side of the photograph. In the years prior to the opening of the school, the children of the mill workers would have found plenty of distractions. The saw mill operation itself would have been an object of fascination, and large sailing ships and their crews from far away would have been arriving, loading, and departing on a regular basis.

- Background

The area now known as Burrard Inlet was occupied by Indigenous peoples thousands of years ago. These peoples formed into nations that had their own distinctive cultures and languages. Beginning as early as the 1500s, their populations were decimated by smallpox which had been brought by Europeans to the Caribbean and Central America and spread north along Indigenous trading routes. In 1862, smallpox broke out in the tiny settlement of Victoria on Vancouver Island. It was brought by gold seekers from San Francisco. An estimated 30 – 50 percent of the Indigenous population of what is now British Columbia was wiped out.

Seventy years earlier, in 1792, Spanish and British explorers had arrived at Burrard Inlet by ship, but European settlement of the area did not begin until the mid 1800s.The first European settlements — the small sawmill communities of Moodyville ( north side of Burrard Inlet) and Hastings Mill (south side of Burrard Inlet) — appeared in the 1860s. In 1871, the Crown Colony of British Columbia joined Confederation as Canada’s sixth province on the understanding that a railroad would soon be built linking British Columbia to the rest of Canada.

One of the first things British Columbia’s government did was pass a Public Schools Act in 1872. It explicitly stated that all public schools would be officially non-sectarian, distinguishing British Columbia from all other Canadian provinces; and that education would be free. The purpose of public education was clearly expressed in the Act as being ‘to give every child in the Province such knowledge as will fit him to become a useful and intelligent citizen in after years….

With its scattered population and small tax base, British Columbia’s early public system was highly centralized. The Province controlled all aspects of the operation of the system and paid all the bills. School trustees were simply responsible for seeing that the provincial regulations were followed and that property was kept in decent condition.

Excerpts from Vancouver Schools—Establishing their Heritage Value

Schools were not necessarily popular with parents, let alone children. The government had to find ways to force local school boards to comply with and enforce various amendments to the Public School Act which made attendance compulsory for children, who remained a useful part of the workforce into the 20th Century, especially during seasonal harvesting , whether the harvest was grain or fish…

The age = grade system as we understand it was not fully implemented until 1923. Schools were ungraded at first, the children progressed individually and learned mostly by rote.

Excerpts from A Highlight History of British Columbia Schools

Other noteworthy dates:

- In 1874, the B.C. Government attempted to reduce student absenteeism by introducing legislation which made teachers’ pay dependent on student attendance. Not surprisingly, teachers were enraged. This measure was soon abandoned.

- In 1876, an amendment to the Public School Act required school trustees to enforce attendance over six months a year for students aged seven to twelve. (In 1901, another amendment to the Act raised the minimum school leaving age to fourteen. In 1921, this was raised to fifteen.) In the same year, a further amendment excluded all clergy from holding a position in a public school and restricted religious practices to the recitation of The Lord’s Prayer and the Ten commandments.

- The First School House

The school-house at Hastings Sawmill operated from 1872 – 1886 as the only school on the south side of Burrard Inlet until 1887.

To begin in the beginning, the first settlement at the point where Vancouver proper now stands clustered around a sawmill, in operation, and known as Hastings mill. This mill was built in 1865; and gradually there began to grow up around it a little village formed of the shacks of the employees. Some of these men brought out their wives and families, and by the year 1872 there were between fifteen and twenty children, white and half breed, of school age in the colony. Then the parent began to feel that they could no longer allow these children to spend their days building castles in the sawdust, playing hide-and-seek among the lumber piles, and growing up in utter ignorance. They must be sent to school.

A spot about 100 yards from the mill, and close to Mr. Alexander’s house, was selected as the site for the school; and a school district was formed with this point as centre, and a radius extending three miles into the primeval forest – no land on the north side of the inlet, of course, to be included. Then lumber was procured from the mill, and a school house 18 x 40 feet erected. Then the mill people having done so much, the government at Victoria was asked to provide a teacher, and Miss Julia Sweney, the daughter of the mill machinist, was appointed the first teacher.

Excerpt from The Romance of Vancouver’s Schools

- ‘The First Day of School’ by Adelaide Patterson

Let me tell you about my first day at the new school, February 12, 1872. I remember it as if it was yesterday. I was only four years old and I was nervous and excited.

Father stoked the stove to get some heat in the rooms, Mother told us to wash well. She wanted us to make a good impression on our new teacher. We put on our best clothes and warm woolen stockings. Abbie, my oldest sister, helped comb my hair and put a new ribbon in it. We could hardly eat breakfast. We were lost in our own thoughts of what school would be like and we were a little apprehensive.

After breakfast Mother inspected our faces, hands, and fingernails and gave us our lunches. Then we pulled on our boots, winter coats, scarves, and mittens. We were reminded to do what we were told as we headed out the door.

It was a 100 yard walk along a wooden plankway to the new school but the plankway was icy and slippery. Some of our friends walked miles to the new school.

We met the Millers: Carrie, Alice, Ada, Fred, Ernest and Bert, and Dick and Fred Alexander on the way to school. Two half-native children and a Kanaka child from Honolulu were already playing outside the school. We chattered excitedly while some of the children chased decay other around the school. Soon, Miss Sweney, dressed in a white blouse, ankle length skirt, and high button shoes, rang the school bell and we marched in.

Miss Sweney had arrived early to light the wood stove and the smarter children scrambled to find seats in the middle of the room – not too near the stove and not too far way. I wasn’t quick enough and ended up near the front. It wasn’t long before I noticed steam rising from my clothes and soon I was unbearably hot.

We sat on benches; my feet couldn’t even reach the floor. Light was provided by heavy brass oil lamps held in wall brackets, Indoor plumbing was non-existent and anyone seeking relief had to brave the cold in the outhouse behind the school.

We were nervous and excited. Some of the older boys were elbowing and teasing the smaller children. There was a lot of chatter but Miss Sweney quickly established order. She explained there would be no talking. “You’re here to learn.” she stated firmly.

One boy paid no attention. Every time Miss Sweney turned away he would spit on the stove to hear the hissing sound on the hot metal. But she seemed to have eyes in the back of her head and she sent the culprit to the back of the room. The outside air creeping through the cracks in the boards chilled his bones all day

There was no blackboard but we all received new slate pencils, copybooks and primers sent from Victoria. Miss Sweney asked us to turn to Page 1. I opened the book and felt embarrassed. I didn’t know the letters of the alphabet I held the book carefully and turned each page slowly. Some students were asked to recite from their books. I pretended to follow – turning the pages when the other children did.

Miss Georgia Sweney, the first teacher at Hastings Mill School. (Photo credit: Vancouver City Archives.)

During recess, Miss Sweney sent us outside to work off a little energy. Some of the children were playing Ante, Ante, Aye Over. They were pitching a ball over the roof while others on the opposite side tried to catch it. I looked for my sisters to calm my nervousness and asked them how I would ever keep up. They told me not to worry; that I’d catch on soon.

After recess we filed back to our seats. Miss Sweney introduced us to number work. It was so confusing. I got lost in all the numbers. I stole a peek around the room and noticed some of the other children having trouble too. I began to feel less alone. But I wished I was back home playing hide and seek with my sisters and friends in the lumber piles or building castles in the sawdust.

The work was easier after lunch. Miss Sweney had us practise writing. I painstakingly copied each letter into my book. Before the day ended Miss Sweney had us singing songs and hymns with the aid of a tuning fork. I decided then, I was going to enjoy school.

Excerpt from Glancing Back: Reflections and Anecdotes on Vancouver Public Schools

- Other teachers who taught at the Granville School House

Miss Sweney was shortly succeeded as teacher by Mrs. Richards, who soon became Mrs. Ben Springer, and cast her lot with the struggling little hamlet, giving place to a Miss Redfern, who after a short tenure of office gave place in turn to Mrs. Catherine Cordiner, still a resident of the city, who taught from 1876 to 1882, and was succeeded by no less a person than Miss Agnes Deans Cameron. She taught for one year, and was followed by two very attractive girls, with whom the big boys persisted in falling in love; and to obviate this difficulty the school board was driven to the expedient of engaging male teachers.

Excerpt from The Romance of Vancouver’s Schools

Portrait of Mrs Catherine Cordiner, teacher at Hastings Mill School from 1876 – 1882. (Photo Credit: Vancouver City Archives.)

Perhaps the school’s best remembered teacher was Agnes Deans Cameron, born in Victoria in 1863. She taught at the school, for six months, from January to June 1883. She is remembered for posting on the school door, the notice, “Irate parents will be received after 3:00 p.m.”

1890: Agnes Deans Cameron. (Photo credit: Vancouver City Archives.)

1890: Agnes Deans Cameron. (Photo credit: Vancouver City Archives.)

Cameron’s career after leaving Hastings Mill is impressive and colourful:

- In 1884, she was the first woman to be appointed principal at a co-educational school in Victoria.

- She was a founder of the British Columbia Teachers’ Institute; later, she served as president of the Dominion Educational Institute.

- She championed such causes as women’s suffrage and pay equity.

- She was a member of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

- In 1905, she and a fellow teacher were accused of allowing their students to cheat on a high school entrance exam. This incident ended with her dismissal and the end of her career in education.

- In 1908, she spent several months exploring the Canadian Arctic, travelling more than 16,000 kilometres, all the way to the Arctic Ocean and back. Later, she wrote a bestselling book about her adventures, ‘The New North’.

………………………

Another account of the early years of Hastings Mill School (taken from STRATHCONA SCHOOL 1873 – 1961, published by Strathcona Elementary School in 1961)

With commendable foresight and sense of community responsibility, the Hastings Mill Company built a one-room school and applied to the provincial government for a teacher. They were told that if a class of fifteen could be enrolled, a teacher would be provided.

Between the Millers and the Alexanders there were only eight children of school age and even if they added two half-breed children and a Kanaka boy who had jumped ship from Honolulu, the enrolment would ‘still be insufficient. The arrival of the Pattersons solved the problem, but it meant enrolling four-year-old Adelaide. The school was opened and the community was officially named the Granville School District; R.H. Alexander and Jonathan Miller were appointed the first school trustees.

Classes started on February 12, 1873, a historic day which marked the beginning of public schooling in this region. It is not too difficult to picture young Miss Georgia Sweeney as she stood on the school steps at nine o’clock and rang the handbell. She was dressed in a white blouse and ankle-length skirt which only partly covered her high-button shoes. We can imagine the fifteen children, scrubbed and polished, dashing into the school house to try out their new seats and get their first taste of real school.

The class consisted of the two half-breed children, the big Kanaka boy, the six Millers – Carrie, Alice, Ada, Fred, Ernest and Bert, the two Alexanders – Dick and Fred, and the four Pattersons – Abbie, Rebecca, Alice and Adelaide. The only member living at the date of this writing is the former Alice Patterson, now ninety-seven year old Mrs. Crakanthorp.

With its clapboard exterior, cedar shake roof, bare walls and floor, the Hastings Mill School was a classic example of the “little red schoolhouse” equipped with bench-like desks and little else. Slates, copybooks, primers, and other necessities were sent over from Victoria.

Despite the lack of amenities, school life was intimate and friendly. Only a hundred yards from the mill, the pupils did their sums and studied their lessons to the musical overtones of the trim saws. On cold mornings the stove at the back of the room was stoked up with wood from the mill and everyone was comfortable. Coal-oil lamps in wall brackets dispersed the gloom on winter days.

The lessons were simple. Reading came first, followed by arithmetic and writing. There was heavy emphasis on rote learning, such as memorizing the names of all the British rulers from William the Conqueror to Queen Victoria. Long poems and facts also had to be absorbed. There were prizes, usually a book, for the best recitations.

At recess the boys played on one side of the school, and the girls on the other. The boys favoured “Ante, ante, aye over!” which involved hurling their missiles over the school house, and the girls played “London Bridge”. Another popular girls’ game had one child in the center of a revolving ring of children holding hands and chanting:

“There was a little dog

His name was Buff

They sent him downtown to buy some snuff

He won’t bite you

He won’t bite you

He WILL bite you!”

In these early years, the children learned much from visitors to the settlement, especially from sea captains and their officers. They also heard all about the balls and dances that were staged in Granville’s dance hall, but they were very proper and formal. Young ladies had to be chaperoned and were not allowed to walk across the dance floor without an escort.

Sometimes parties were held in the school house and the country-side rang with the singing and the organ music. According to the former Alice Patterson, Mrs. Alexander was often called upon to sing as she possessed a superb voice, and Mrs. Richards, who succeeded Miss Sweeney as teacher, played the organ which had been supplied by the school authorities. Not long after her arrival, Mrs. Richards managed to buy a piano from the wife of a visiting sea captain, and this was a valuable acquisition to the little community. During the school day the piano was a central part of the activities, as it was on all festive occasions.

The children had no time to be bored, especially with so many ships in port for as long as three to six months while their lumber cargoes were being cut and loaded by hand. It was common for fifteen to twenty ships, both steam-powered and sailing ships, to be lying about the harbour at anchor while the stevedores laboriously packed their holds. Meanwhile, the ships” officers and crews were entertained royally by the townspeople. On one memorable occasion, the visiting captains, anxious to return the compliment, organized a huge party aboard a large scow which they had towed up the inlet on a fine summer’s day. It was a real picnic; the entertainment included a musical group, mountains of food, dancing and excursions ashore.

In this setting, the little Hastings Mill School provided formal education for thirteen years. At the end of each term, when report cards were given out, the parents were invited to the closing exercises. The programme included singing, recitations, and prizes for various accomplishments. In these thirteen years the community did not grow very much. It is true that more families moved into the area and that the school was, by 1886, overcrowded, but there was no other industry to attract a large population.

- The Founding of Vancouver

The origin of the City of Vancouver, and the subsequent creation of the Vancouver School District, are linked directly to the completion of Canada‘s first transcontinental railroad. In 1884, William C. Van Horne, General Manager of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company, visited Burrard Inlet. After surveying the area, he declared that Granville, a small settlement lining the shoreline about halfway between Stanley Park and the Hastings sawmill would be the western terminus of Canada’s first intercontinental railway. He renamed the settlement ‘Vancouver’ as he felt it was a more memorable name.

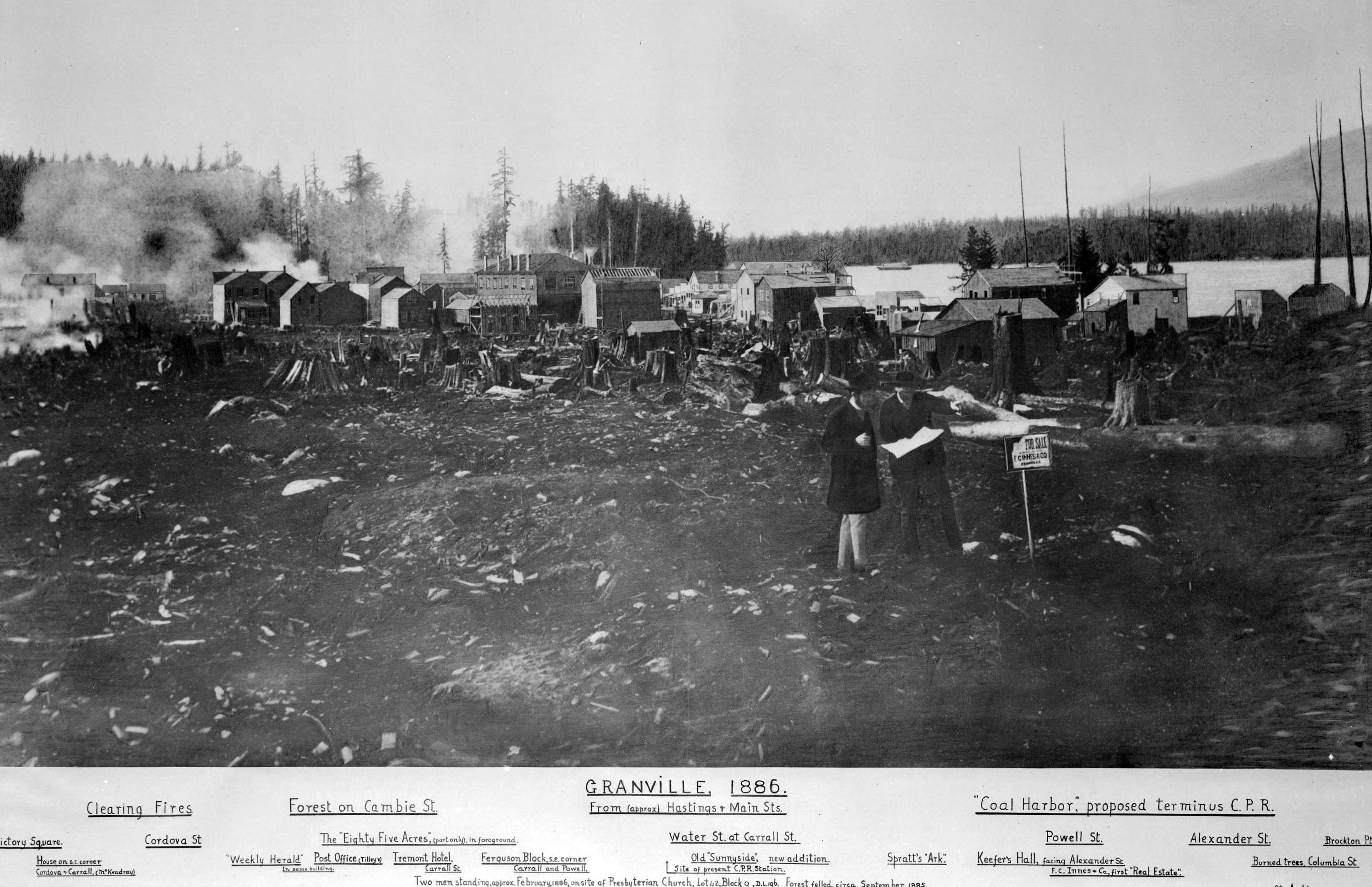

Vancouver in 1886. (Photo credit: Vancouver City Archives)

In 1884, William C. Van Horne, General Manager of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company, visited Burrard Inlet. After surveying the area, he declared that Coal Harbour, just east of Stanley Park, would be the western terminus of Canada’s first intercontinental railway. The terminus was named Vancouver.

The City of Vancouver was incorporated on April 06, 1886. Its boundaries were far smaller than those of today: 16th Avenue to the south, Alma Street to the west, and Nanaimo Street to the east. The large area to the south of 16th Avenue was incorporated in 1892 as the District of South Vancouver. In 1908, this District was divided into two municipalities: the Municipality of Point Grey and the Municipality of South Vancouver.

Just 10 weeks after Vancouver was incorporated, a terrible fire destroyed most of the city. Dozens of people died. The school-house at Hastings Mills remained standing after the fire and was used as a shelter by some of the survivors. The building never re-opened as a school. The school reopened for a short time after the summer break, but closed permanently on November 04, 1886. It was too small, and work on the new Canadian Pacific Railway line had left it perched above a deep railway cut. Also, construction of a new school house a few blocks away was nearing completion.

June 11, 1886. Hastings Mill School 2 days before the Vancouver Fire. (Photo credit: Vancouver City Archives.)

June 11, 1886. Hastings Mill School 2 days before the Vancouver Fire. (Photo credit: Vancouver City Archives.)

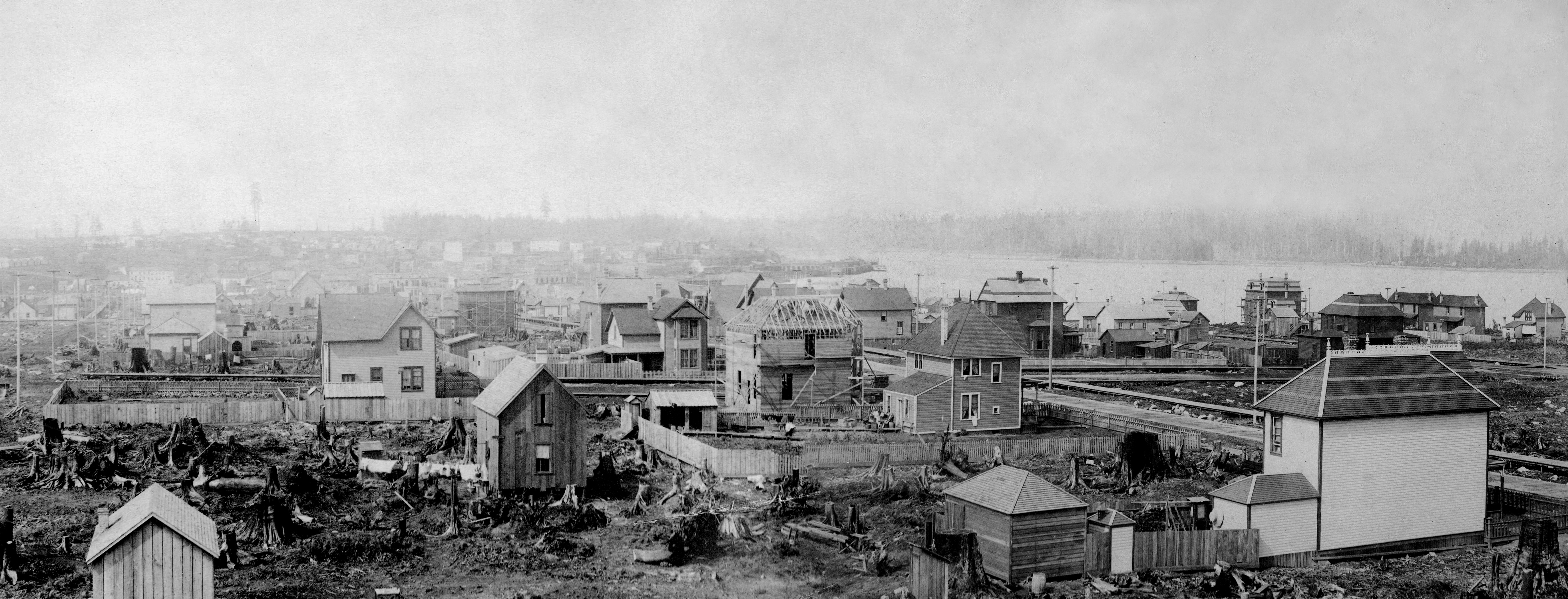

July 1886. The view looking southwest from Hastings Mill three weeks after the Great Vancouver fire. The school house would have been located off to the left of the photo. (Photo credit: Vancouver City Archives.)

July 1886. The view looking southwest from Hastings Mill three weeks after the Great Vancouver fire. The school house would have been located off to the left of the photo. (Photo credit: Vancouver City Archives.)

A description of the Vancouver fire taken from STRATHCONA SCHOOL 1873 – 1961, published by Strathcona Elementary School in 1961.

Fire struck the community on Sunday, June 13, 1886, a clear and hot day. A thin haze of blue smoke hung over the city as men clearing on the C.P.R. property, in what is now the West End, burned slash. Just be-fore noon a westerly breeze sprang up, spreading acrid smoke and cinders over the townsite and surrounding forest. Shortly after two o’clock the wind stiffened into a strong westerly which fanned the brush fires and showered sparks over a wide area. Almost in no time, it became a forest fire that advanced fiercely to the cluster of homes and buildings.

Horror and panic shook the residents as they fought to escape the holocaust which roared through homes and buildings. As trees and buildings crashed, sending up showers of sparks and ashes, people grabbed what they could of their belongings and ran wild-eyed for the inlet, lungs seared, their ears filled with the roaring and crackling of fire out of control. Carrie Miller just had time to grab her winter clothes and flee, dragging her mother with her. Estella Johnston crammed everything she could lay hands on into a tablecloth and fled, but not before she had care-fully locked the door and put the key in her pocket. One old lady seized her dead husband’s picture and made off for New Westminster on foot. Most scrambled for safety in False Creek. Some, in their unseeing rush, fell down open wells and drowned. Children were lost in the confusion. On the waterfront people struggled to put makeshift rafts together. All available boats were used for a shuttle service to ships at anchor.

In forty minutes it was all over and. Vancouver was a smoking ruin. An estimated dozen persons perished in the flames which wiped out all except three or four buildings including the Alexander residence and the Hastings Mill School, both of which were at the lower end of Dunlevy Street. Houses such as the Soule’s residence on upper Dunlevy Street were destroyed. The fire burnt itself out at about this point, cutting an arc into the East Forest just beyond what is now Main Street. The mill itself was untouched.

The disaster stunned the people. Temporary quarters for the home-less were set up in the two mills, in the homes of Moodyville and New West-minster people and on the Captain Soule’s barque, the Robert Kerr, which was lying at anchor in the harbour. As for the dispossessed, they set to work with astounding vigour to rebuild their homes. Before long bigger and better houses dotted the countryside pushing roads into the East Forest. From that moment on, the City of Vancouver became a boom town.

While the Great Fire stopped short of the Hastings Mill School, it did set up new conditions which caused the school to be abandoned. The new town which arose out of the fire needed a larger school in a more central location. This was built on Oppenheimer Street.

………………….

The fire proved a temporary setback. Rebuilding occurred very quickly. Then, in May 1887, after trains began arriving in Vancouver, the city’s population grew rapidly, from 1,000 in 1887 to 9,000 in 1889. Telegraph services arrived with the trains, connecting city to a global system of rapid communication.

May 23, 1887: The first train arrives at the Canadian Pacific Railway Station in Vancouver. (Photo credit: Vancouver City Archives.)

May 23, 1887: The first train arrives at the Canadian Pacific Railway Station in Vancouver. (Photo credit: Vancouver City Archives.)

The fire proved a temporary setback. Rebuilding occurred very quickly. Then, in May 1887, after passenger trains began arriving in Vancouver, the city’s population exploded. It grew from 243 in 1881 to 13,647 in 1891. This increase put huge pressure on those providing public schooling.

- New Schools

In November 1886, the Granville School District had been replaced by the Vancouver School District. The Vancouver Board of School Trustees responded to the rapidly growing student population by calling for the construction of three new schools and a multi-purpose two-room building.

a) East School (also known as Oppenheimer Street School)

East School opened on January 26, 1887. It was located at what is now 522 East Cordova Street, about five blocks south of the location of the Hastings Mill school-house.

Structure: two-storey, frame building, four classrooms.

Cost: $3,500.00

Principal: Mr. J. W. Robinson – salary $70 per month (replaced by Mr. H. Pottmeyer in January 1888, who was replaced in turn by Mr. R. Law in September 1888.) Teachers’ salaries were $50 per month.

Sir – In compliance with your request, and in accordance with the regulation therein referred to, I beg to submit my report of the Vancouver Public School for the year ending June 30th, 1887. I opened school in the new building January 26th with one assistant, and an enrollment of 93 pupils, which increased so rapidly that soon the rooms were crowded. In the early part of April the Government furnished the two upper rooms of the building, and on the fifteenth of that month they were declared ready for occupation. A second assistant was then engaged, and the classes were divided to the best advantage. Though this reduced the number of classes in each division, it did not lessen the number of pupils in the various rooms for many who had been debarred through want of accommodation now came flocking in, till at the close of the term there was an enrollment of 285 pupils , as shown by reports…

It is to be regretted that no play ground has been secured in connection with so large a school, and as the little plot on which the school stands has not been cleared and leveled, we have had no convenient place on which to drill or marshal the pupils…

A large number of ladies and gentlemen were present at the closing examination, , and after examining the classes in the various branches a rather limited number of prizes were awarded to the most meritorious, and with a few speeches and the National Anthem, the school closed for the holidays.

Excerpts from the Annual Report of the Principal, Mr. J. W. Robinson to the Superintendent of Education, Victoria (September 13, 1887)

In order to meet present requirements, another school-house should be erected in the western part of the city. Should this suggestion receive favorable consideration, the separation of the sexes would be advisable. The district would then possess a Boys’ School and a Girls’ School in separate buildings, which would prove to be of great advantage to the educational interests of the city.

Recommendation by School Inspector (1887)

The Oppenheimer Street School was for the most part surrounded by a narrow margin of ground protected by a narrow margin of ground, protected by a high board fence. There was room for no games except “Knife”, “Alley;”even “Hopscotch” and “Leapfrog” had to wait a better day. So pupils did not learn to play fair, and often complaints met the teacher’s ear.

While teaching in this School, it was customary for the pupils (and teachers too) to follow the cattle, or old logging trails south-easterly through a varied woods to False Creek. “Skid roads” largely served to carry through the then partly dismantled forest. This range of playground made up for the lack at school of such. The more stately trees had been drawn off for lumber, yet there remained some large cedars and firs – some fully five feet in diameter. The underbrush was thick, largely made up of salal and blackberry, interspersed with alder, crab apple, and salmonberry.

Excerpt from A History of Vancouver’s Schools

1887: Group Photo – East School, also known as Oppenheimer Street School. The assistant, Miss Alice Christie, can be seen in the lower left of the doorway. (Photo credit: Vancouver City Archives.)

1887: Group Photo – East School, also known as Oppenheimer Street School. The assistant, Miss Alice Christie, can be seen in the lower left of the doorway. (Photo credit: Vancouver City Archives.)

1887: View looking northwest from Jackson Avenue near Oppenheimer Street (now called East Cordova Street), the approximate location of East School. (Photo credit: Vancouver City Archives.)

1887: View looking northwest from Jackson Avenue near Oppenheimer Street (now called East Cordova Street), the approximate location of East School. (Photo credit: Vancouver City Archives.)

… Although I’m aware that the teacher’s task is nowhere a light one, I found it doubly onerous in this city. According to recent estimates, Vancouver more than doubled the number of its inhabitants during the past year, and, consequently, a great number of new pupils, trained in various parts of the Dominion, the United States, and the British Isles, entered the school during the term. To classify these pupils was a matter requiring great discrimination, and involving more than ordinary difficulty….

The school-grounds, formerly in very bad condition, present an attractive appearance since they were graded and fenced. It is to be regretted, however, that they are so small as to accommodate only a limited number of children. In my opinion, play-grounds should not be looked upon as a mere matter of convenience; they should be regarded as an effectual means for the intellectual and moral growth of the pupils.

August 15, 1888 – Annual Report of the Principal, Heinrich Pottmeyer to the Superintendent of Education, Victoria.

b) West School

Structure: Four-room, fame building built during the summer of 1888. Located at the corner of Burrard and Barclay. All four rooms were in use by January 1889

Principal: Miss M. Hartney, until June 30, 1889 – salary, $70 per month

Assistants: three (salary: $50 –$ 55 per month)

Students: 118 students occupying 3 rooms when the school opened in November; 321 enrolled during the year.

Group photo – ‘West End’ or ‘West’ School, later the location of Aberdeen School, 1897. (Photo Credit: Vancouver City Archives.)

… The attendance, however, would have been considerably larger were it not for sickness that was so prevalent among the children during the spring months. And this sickness, I am convinced, was much aggravated by the school grounds, which are in very unfavorable condition, and require immediate attention in order to preserve the health of pupils and teachers. As this school has been only a short time in operation, and many of the pupils had not been attending any school for months previously, I consider the progress made by them in the different subjects has been very satisfactory, judging from the result of the promotion examination held in each of its divisions.

Excerpt from the Annual Report of the Principal, Miss M Hartney to the Superintendent of Education, Victoria, July 04, 1889

c) False Creek School

Structure: Three small frame building joined together, located at what is now Broadway and Kingsway. It was open from 1887 – 1892.

Staff (1887): one teacher, one assistant

Students: 141 enrolled during the 1888 – 1889 school year

According to reports, bears sometimes frightened children going to and from the school.

Funeral procession on what is now Kingsway passing in front of three buildings comprising False Creek School (also known as the old Mount Pleasant Building), 1893. (Photo credit: Vancouver City Archives.)

d) A multi-purpose two-room building located at Hastings and Hamilton Streets

This structure was used by senior elementary school students prior to the opening of Central School in January, 1890.

From August 1890 to June 1893, it was used by high school students (see below) during the construction of Vancouver’s first high school. Later, for a short time, it housed offices of the Vancouver School Board.

e) North Arm School: Vancouver’s second oldest school

Top: North Arm School – original building (photo taken in 1912.) Bottom: North Arm School – group photo (1910.)

Top: North Arm School – original building (photo taken in 1912.) Bottom: North Arm School – group photo (1910.)

The second oldest school in the Vancouver area was North Arm School. It was located at what is now the intersection of Marine Drive and Fraser Street. It opened in 1876 in a one-room school house, and closed in 1925 in a larger multi-classroom building. The school served the farming and fishing families that lived along the Fraser River.

Strictly speaking, the school was never part of the Vancouver School District. Rather, it was located in the Municipality of South Vancouver. In 1929, this Municipality, along with the Municipality of Point Grey, amalgamated with the City of Vancouver, and its schools became part of the Vancouver School District. However, by that time the school’s name had changed twice: Simon Fraser (1925), Captain Cook (1928). In 1929, the school was renamed Moberly Annex (A).

Date: 1915 Point Grey School Board (Photo Credit: Vancouver City Archives)

8. Milestones in Public Education (excerpts from A Short History of BC Education, University of Victoria)

- 1851 Governor James Douglas recommends that schools be established for “the children of the laboring and poorer classes” in the Colony of Vancouver Island.

- 1870 Rules and Regulations for the Management and Government of Common Schools are published in the Government Gazette for the benefit of parents, teachers, and school trustees. Appendices to the Rules and Regulations list prescribed textbooks and provide prayers to be used in religious services.

- 1872 In March the provincial legislature adopts the Public School Act (1872). This statute creates a Public School Fund and a Provincial Board of Education.

- 1876 The Public School Act, 1872 is subsequently amended to exclude all clergy from holding any position – voluntary or otherwise – in a provincial public school. The amendment also restricts religious exercises in schools to the public recitation of The Lord’s Prayer and the Ten Commandments.

- 1879 Public School Act, 1879. The position of Superintendent of Education is retained, but the Board of Education is abolished under the new act. Control of the public school system is placed with the Lieutenant- Governor-in Council (i.e. the Cabinet.)

Excerpts from A Highlight History of British Columbia Schools by Shirley Cuthbertson (Royal BC Museum)

When Vancouver Island was declared a Crown Colony in 1849, James Douglas, Chief Factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, invited the Reverend Robert Staines, a Church of England Minister, to become both Company Chaplain and schoolmaster for children of Company officers. Shortly after his arrival, the Oblate mission delegated Father Honore Timothy Lampfrit to teach children of Roman Catholic parents. As settlers arrived, Douglas supported other schools, most of which charged fees. Girls could be sent to a school for “young ladies”, but if parents could not afford it, girls stayed home…

By the mid-1860’s there was strong support for free “common schools”, which were established with the Common School Act in 1865 on Vancouver Island. The argument for non-sectarian schools was led by the editors of the two leading newspapers on Vancouver Island and in New Westminster. Both men advocated free public non-sectarian education, based on the principle of equality of opportunity, and both gained public support for their positions. Amor de Cosmos, editor of the Colonist, wrote in 1865: “We are not disposed to cavil at the imperfections of the bill so long as the two great principles – free schools and a non-sectarian system of education – are enunciated.”

When the colonies were joined, Governor Seymour opposed free common schools, and withheld funding. Many schools had closed by 1869. The Common School Ordinance that year centralized control in the hands of the Governor-in-Council, with state support for education of $500 per year per teacher. The Government had the power to create school districts, apportion grants, to appoint, certificate, inspect and dismiss teachers, and to make rules and regulations for the management of schools…

A provision of the British North America Act, Canada’s document of confederation, was that education was to be the responsibility of the provincial governments… The Public Schools Act of 1872, which provided for education from the general revenues of the province, allowed the government to appoint a Board of Education and a Superintendent and to establish school districts. The objective of the Act was “to give every child in the Province such knowledge as will fit him to become a useful and intelligent citizen in after years…”

Schools were not necessarily popular with parents, let alone children. The government to find ways to force local school boards to comply with and enforce various amendments to the Public School Act which made attendance compulsory for children, who remained a useful part of the workforce into the 20th century, especially during seasonal harvesting, whether the harvest was grain or fish. Again, the Nanaimo teacher’s register notes students who left school to work.

In 1874 the teaching staff were almost all untrained teachers – there were 17 men and 15 women – 14 English, 6 Scots, 2 Irish, 2 Americans and 8 Canadians. School houses were almost all of frame or wood construction, only two in 1874 were made of logs. They were heated by stoves, (in some cases fireplaces), and were sparsely furnished with benches or desks and most (but not all) with slate blackboards. Jessop provided each with a set of maps and a “terrestrial globe”. School books were authorized and purchased by the Department of Education and sold through the schools to the children…

The age = grade system as we understand it was not fully implemented until 1923. Schools were ungraded at first, the children progressed individually and learned mostly by rote. By 1884, larger urban schools were “graded”, and although pupils still went through the series of readers individually, a teacher would have the lower book children (“primary” from “primer”) or the higher book children. “Rural” schools continued much longer with individual progress measured by “reader” level.

The first public high school in British Columbia was Victoria High School – later known as “Vic High”… The curriculum included: “ENGLISH: Geography, ancient and modern, Grammar, Rhetoric and Composition, Mythology; SCIENTIFIC: Botany, Physiology, Natural Philosophy, Astronomy and Chemistry; MATHEMATICAL: Arithmetic, Algebra, Mensuration, Euclid, and Book-keeping; CLASSICAL: Latin and Greek; MODERN LANGUAGES: French; together with Map drawing, vocal music, &c.” The two teachers each taught all of these subjects until they divided them in 1880.

“British Columbia had entered Confederation with the most centralized school system on record.” (Johnson, 88) Gradually, as the cost of education rose, the government was forced to share both costs and control with local authorities.

The Public Schools Act of 1888 shifted more of the cost of education to local government, and more powers were granted to the local boards, which were no longer elected in cities: three were appointed by the Provincial Government and four, including the chairman, by the city council.