In class today we learned about some of the customs and stories associated with Chinese New Year. Then we got creative and made some dragons!

In class today we learned about some of the customs and stories associated with Chinese New Year. Then we got creative and made some dragons!

In class today we learned about some of the customs and stories associated with Chinese New Year. Then we got creative and made some dragons!

In class today we learned about some of the customs and stories associated with Chinese New Year. Then we got creative and made some dragons!

Today’s class was called

If you want to hear the story ‘When Charlie met Emma’ again, click HERE and you will be taken to a video recording of me reading the story. Or go to the BOOKS section of our blog and scroll through until you find it.

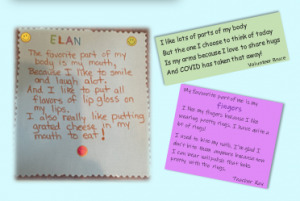

For the activity today I asked you to measure your height with a piece of string (or ribbon), stick the string onto a piece of card and tie it in a big bow. Then write your name and age on the piece of card along with this poem:

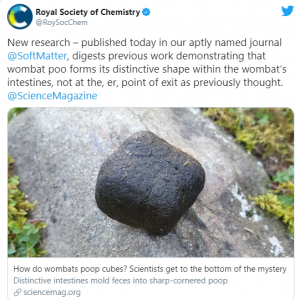

Did you know that Wombat poops are square shaped? (Or to be more accurate, ‘rectangular prism shaped’)

Wombats are a type of Australian marsupial and the only animals in the world that are known to produce ‘square’ shaped poop!

Scientists are pretty sure that Wombats, like many other animals, communicate through their poop by using it to mark out their territory. Wombat’s like to poop on top of rocks to make sure everybody can smell it and get the message! But most poops would roll off a rock! The Wombat’s ‘square’ poop is much more likely to stay on the rock and not roll away.

Well, that’s been baffling scientists for a long time! But now they think they have the answer.

How wombats produce their cube-shape poo has long been a biological puzzle but now an international study has provided the answer to this unusual natural phenomenon.

The cube shape is formed within the intestines – not at the point of exit, as previously thought – according to research published in scientific journal Soft Matter on Thursday.

The paper expands upon preliminary findings first presented at a meeting of the American Physical Society’s fluid dynamics division in Georgia in 2018.

Dr Scott Carver, wildlife ecologist at the University of Tasmania and one of the authors of the research paper, said “there were wonderfully colourful hypotheses around but no one had tested it”.

There was speculation that wombats had a square-shaped anal sphincter, that the faeces get squeezed between the pelvic bones, as well as the “complete nonsense” idea that wombats pat the faeces into shape after they deposit them.

The project originated four years ago when Carver was dissecting a euthanised wombat hit by a car and noticed the cubes in the last metre of the wombat’s intestine. Carver described it as an “isn’t that odd moment”.

“The thing that is striking, how do you produce cubes inside essentially a soft tube?”

The team of researchers in Australia, including the head veterinarian at Taronga zoo, Larry Vogelnest, tested the tensile strings of the intestine while physicists in the US based at the Georgia Institute of Technology created mathematical models to simulate the production of cubes.

The team discovered big changes in the thickness of muscles inside the intestine, varying between two stiffer regions and two more flexible regions.

“The rhythmical contractions help form the sharp corners of the cubes,” Carver said.

When preliminary findings were presented in 2018 “at that point researchers believed there were four stiff and four flexible regions,” he said. “But what final research has confirmed is that the wombat’s intestine has two stiff and two flexible regions.”

Since 2018, Australian researchers have performed the histology as well as a CT scan upon a live wombat, and concluded that the changes in muscle thickness, in addition to the drying out of the faecal material in the distal colon, produced the distinctive shape.

Asked why wombats have this feature, Carver said one theory was that wombats, with their strong sense of smell, communicate with each other via faeces and that the cube shape helps prevent the faeces from rolling away.

The researchers also found that cube-shaped faeces on an eight degree slope rolled far less than spherical-shaped models.

Vogelnest aided the research by facilitating an ethically approved CT scan of a live wombat, zoo resident Lucy-Lu.

“This was one of the more unusual research [projects] Taronga has been involved in, a bit quirky, but it does answer a very significant question, one that a lot of people ask” he said.

As well as the benefits of better understanding wombats themselves, Carver said the discovery highlighted a new way of manufacturing cubes inside a soft tube, which could be applied to other fields including manufacturing, clinical pathology and digestive health.

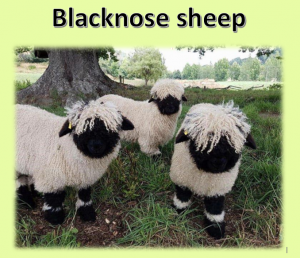

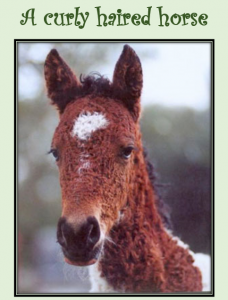

This week we are looking at Farms in our zoom classes.

I recently found two cute types of farm animals that I’ve never seen before!

What do you think?

Thanks to Craig Beals for another great video!

A reminder about how to find your blind spot