Two Spirits, One Voice is a community-based initiative that seeks to bolster supports for persons that identify both as LGBTQ and Indigenous –Two Spirit people. Please click her for video.

Please contact the Urban Native Youth Association for student support in the VSB. UNYA runs programs for youth who identify as LGBT and Two Spirit.

From the website:

Who Are Two Spirited People?

“Two Spirit identity is about circling back to where we belong, reclaiming, reinventing and redefining our beginnings, our roots, our communities, our support systems and our collective and individual selves”

– ALEX WILSON

In 1990, Myra Laramee coined the term Two Spirit, which was adopted at a gathering of native American and Canadian LGBTQ people in Manitoba. Some indigenous people choose to identify as Two Spirit rather than, or in addition to, identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans or queer. Prior to European arrival, Two Spirit people were respected members of their communities and were often accorded special status based on their unique abilities to understand both male and female perspectives. These identities were recognized and celebrated from a young age as gifts from the creator; Two Spirit people were often the visionaries, healers and medicine people. The term Two Spirit affirms the interrelatedness of all aspects of identity — including gender, sexuality, community, culture, and spirituality. It is an English term used to stand in for the many indigenous words for those with sexual and gender diverse identities. Many Two Spirit and their teachings were lost due to the impacts of colonization. An understanding of the complexities of Two Spirit people, builds wisdom in understanding their culture and intersectionality.

About Two Spirit, One Voice

The program is being piloted in 4 communities across Ontario; Toronto, Thunder Bay, Sault Ste. Marie, and Kenora. We offer free-of-charge facilitated workshops that guide participants through conversations of equity and inclusion that engage both LGBTQ and indigenous issues in order to reach a more full understanding of barriers, histories, and resiliencies that these populations face. Participants will also be guided through unique resources to better understand best practices for supporting Two Spirit community members.

Two Spirit Allyship

“Everyone has a purpose. And, the Creator doesn’t make any junk.”

– WILLARD PINE, ELDER OF GARDEN RIVER FIRST NATION

When it comes physical wellness, mental health, emotional wellbeing, and spiritual needs, we need to be mindful of our actions and inactions,.This is the most important idea for practicing allyship for Two Spirit and LGBTQ indigenous people. So what does it mean?

To be an ally for Two Spirits you need to be against queerphobia and racism. Being an ally requires humility as well as a commitment to listening, learning and challenging your own assumptions.

Here are some tips for practicing allyship:

- Educate yourself on the experiences and perspectives of Two Spirit people.

- Identify relevant resources out there and be ready to refer someone in need.

- Reflect stereotypes and assumptions you hold on LGBTQ and Indigenous peoples

- Know how to Intervene when racism, homophobia, biphobia and transphobia happen.

Some additional questions to consider:

- Would you be comfortable supporting families who have youth in the coming out process?

- Are able to support the choice of Two Spirit trans* people in using the pronouns of their choice?

- Do the policies of your community or organizations reflect the experiences of Two Spirit identities?

- How would you support an LGBTQ person in crisis?

- Where can you find more information and seek training opportunities to learn more?

Redefining Warriors

“Warriors are men & women who can cry, who can admit their mistakes and admit their fears, and walk forward to help others”

– TWO SPIRIT ELDER MA-NEE CHACABY

What does it mean to be a warrior? The idea of a warrior is often connected to masculinity; a warrior masculinity that has been cemented over generations of colonial resistance. Our once flexible gender roles have become rigid,often putting those who fall outside of what it means to be a ‘man’ or a ‘woman’ in a dangerous place. We must acknowledge that there are deep connections between misogyny and homophobia, biphobia and transphobia.

Though Two Spirit people were once an integral part of community balance across Turtle Island, through the on-going processes of colonization and christianization, male-dominated forms of governance have been woven into the social fabric. Healing from trauma and returning Two Spirit identities to their rightful place in indigenous communities must call into question patriarchy as a naturalistic system.

Unpacking and unlearning rigid gender norms, homophobia and transphobia is part of the healing process that all people must work towards. Being truthful with our own identity leads to bravery. And by asking honest questions can build an understanding of reconciliation for Two Spirit people.

Two Spirit Role Models

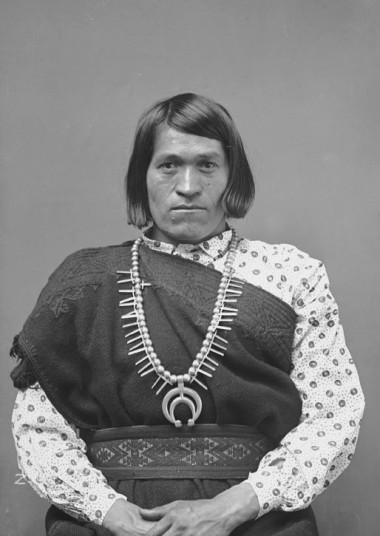

We’wha (1849–1896, various spellings) was a Zuni Native American from New Mexico. They were the most famous lhamana, a traditional Zuni gender role, now described as mixed-gender or Two-Spirit. Lhamana were men who lived in part as women, wearing a mixture of women’s and men’s clothing and doing a great deal of women’s work as well as serving as mediators.

We’wha (1849–1896, various spellings) was a Zuni Native American from New Mexico. They were the most famous lhamana, a traditional Zuni gender role, now described as mixed-gender or Two-Spirit. Lhamana were men who lived in part as women, wearing a mixture of women’s and men’s clothing and doing a great deal of women’s work as well as serving as mediators.

We’wha is the subject of the book The Zuni Man-Woman by Will Roscoe. The anthropologist Matilda Coxe Stevenson also wrote a great deal about We’wha, and even hosted them on their visit to Washington D.C. in 1886. During that visit, We’wha met President Grover Cleveland and was generally mistaken for a cisgender woman. One of the anthropologists close to them described We’wha as “the strongest character and the most intelligent of the Zuni tribe” (Roscoe, 1991, p. 29). She is historically known mainly for the fact that she was man but chose to live out her life as a woman. In the nineteenth century this status was called berdache, being anatomically one sex but performing tasks that were equated with the other (Roscoe, 1991, pg.29). In We’wha’s case she was a man but performed tasks of a Zuni woman. During her lifetime she came in contact with many white settlers, teachers, soldiers, missionaries, and anthropologists. One anthropologist she met was Matilda Coxe Stevenson, who would later become a prominent figure in We’wha’s life. Stevenson wrote down her observations of We’wha, going on to state, “She performs masculine religious and judicial functions at the same time that she performs feminine duties, tending to laundry and the garden” (Suzanne Bost, 2003, pg.139).

Kent Monkman is an artist of Cree ancestry who works with a variety of mediums, including painting, film/video, performance, and installation. He has had solo exhibitions at numerous Canadian museums including the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, AB, the Montreal Museum of Fine Art, the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art in Toronto, the Winnipeg Art Gallery, and the Art Gallery of Hamilton. He has participated in various international group exhibitions including: The American West, at Compton Verney, in Warwickshire, England, Remember Humanity at Witte de With, Rotterdam, the 2010 Sydney Biennale, My Winnipeg at Maison Rouge, Paris, and Oh Canada! at MASS MOCA.

Kent Monkman is an artist of Cree ancestry who works with a variety of mediums, including painting, film/video, performance, and installation. He has had solo exhibitions at numerous Canadian museums including the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, AB, the Montreal Museum of Fine Art, the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art in Toronto, the Winnipeg Art Gallery, and the Art Gallery of Hamilton. He has participated in various international group exhibitions including: The American West, at Compton Verney, in Warwickshire, England, Remember Humanity at Witte de With, Rotterdam, the 2010 Sydney Biennale, My Winnipeg at Maison Rouge, Paris, and Oh Canada! at MASS MOCA.

Monkman has created site specific performances at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, The Royal Ontario Museum, The Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian and at Compton Verney, he has also made super 8 film versions of these performances that he calls “Colonial Art Space Interventions.” His award-winning short film and video works have been screened at various national and international festivals, including the 2007 and 2008 Berlinale, and the 2007 Toronto International Film Festival.

Monkman is working towards solo exhibitions at the McCord Museum in Montreal Qc and the Denver Art Museum in Denver, Co. His work will also be included in group shows at The National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, On, The Leslie Lohman Museum in NYC, Ny and la Galerie UQAM in Montreal, Qc.

His work is represented in numerous public and private collections including the National Gallery of Canada, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Museum London, The Glenbow Museum, The Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art, The Mackenzie Art Gallery, the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian and The Vancouver Art Gallery. He is represented by Pierre-Francois Ouellette Art Contemporain in Montreal and Toronto, Galerie Florent Tosin in Berlin, and Trepanier Baer in Calgary.